Publisher David Loeb had his Bay Nature epiphany while hiking in China Camp State Park. That’s when he conceived of the idea to start a magazine about the natural wonders of the San Francisco Bay Area.

David also spoke on the Bay Area’s unique geological dynamics and how they combine with ocean upwelling to create its microclimates.

>> Listen to the podcast at the Oakmont Symposium’s website.

Below is a transcript of David’s talk:

“Thanks to the organizers of the Oakmont Sunday Symposium for inviting me to speak today about Bay Nature and about Bay Area nature.

I’d like to start out by asking how many of you know about or have heard of Bay Nature magazine? How many of you have read it? Okay great, thanks. And just one more question: How many of you consider yourselves nature-lovers? Terrific; thanks!

I generally start out my talks by acknowledging my complete lack of credentials. As the publisher and co-editor of a magazine dedicated to exploring the natural world of the Bay Area, it is my responsibility to find people who ARE experts in topics related to the natural world, get them to write about their areas of expertise, and then frame and shape that knowledge and those experiences into a coherent, compelling story.

I try to learn enough about a topic to be an intelligent editor, enough to shape that story in the best way possible for our audience … and then move on to the next issue of the magazine and a whole different set of topics. So it’s fair to say that in general I know a little about a lot of things, but not a lot about any one thing. Except, perhaps, for publishing a successful, independent, nonprofit regional nature magazine and to keep it going with a small amount of capital and a huge amount of community support, even as so many other magazines have fallen by the wayside. And I guess my one other credential is that I’m passionate about nature – experiencing it, learning about it, and sharing it with others.

So starting from strength, I’d first I’d like to describe what Bay Nature is, and then get into the question of “Why Bay Nature”. And then, if we have time, I’ll share my observations about what makes the Bay Area such a special place ecologically.

Bay Nature is a quarterly magazine dedicated to exploring the natural world of the San Francisco Bay Area, which we defined as the nine Bay Area counties, but sometimes stretching north, south and east to encompass areas like the Monterey Peninsula and the Delta. The magazine was launched January 2001. This is the cover of that first issue. My partner at the time was Malcolm Margolin, publisher of Heyday Books in Berkeley. I was the editor, Malcolm was the publisher.

By 2004, the magazine had become established enough for us to form our own independent nonprofit organization, the Bay Nature Institute. At that time, Malcolm stepped aside and handed the publisher’s wheel over to me.

And this was the cover of our 10th Anniversary issue, in January 2011. Since our launch, we’ve published 53 consecutive quarterly issues while also establishing several other programs to carry out the organization’s mission to connect people with the natural world where we live. Besides publishing the magazine, we also operate a website, baynature.org, which serves as an online portal to nature and conservation in the Bay Area. We sponsor Bay Nature on the Air, a series of video spots highlighting the natural diversity of Northern California that is hosted by your local PBS affiliate KRCB and occasionally features Santa Rosa-based naturalist Michael Ellis, who is also a regular contributor to the magazine. And we sponsor a series of free, naturalist-led hikes and outings to places covered in the magazine. So we’re proud to say that Bay Nature explores the natural world of the Bay Area in print, online, in the field, and on the air.

So that’s the “what” in a nutshell. How about the “why”?

With so many books, magazines, websites, emails, tweets, and blog posts competing for our attention, and with all the dire problems in the world, do we really need ANOTHER thing to read, a magazine about the beautiful places and charismatic wildlife that are part of the natural world where we live? Why is a local nature magazine worth doing and worth supporting? Honestly, I do think about this, because I can assure you we don’t do it for the money!

First of all, we do it in part just for the sheer joy of sharing our experiences in the natural world. I think we all have a tendency to lose touch with those moments of ephiphany and wonder in nature that led us to care so deeply about the environment in the first place. But then I go out for a hike and discover spectacular views and breathtaking wildflower displays at a place I’d never been before.

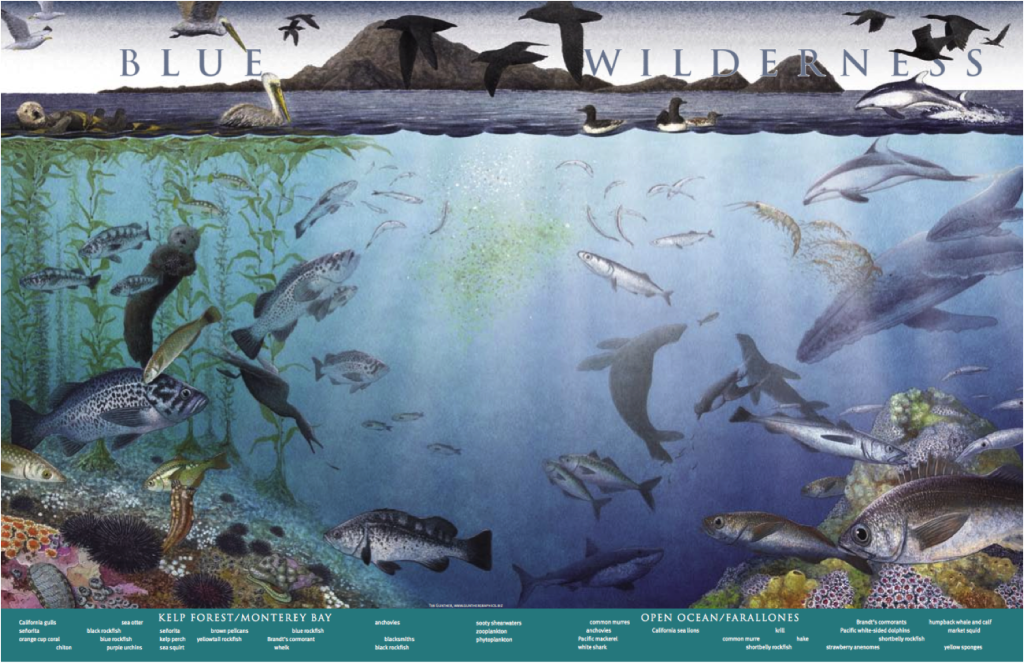

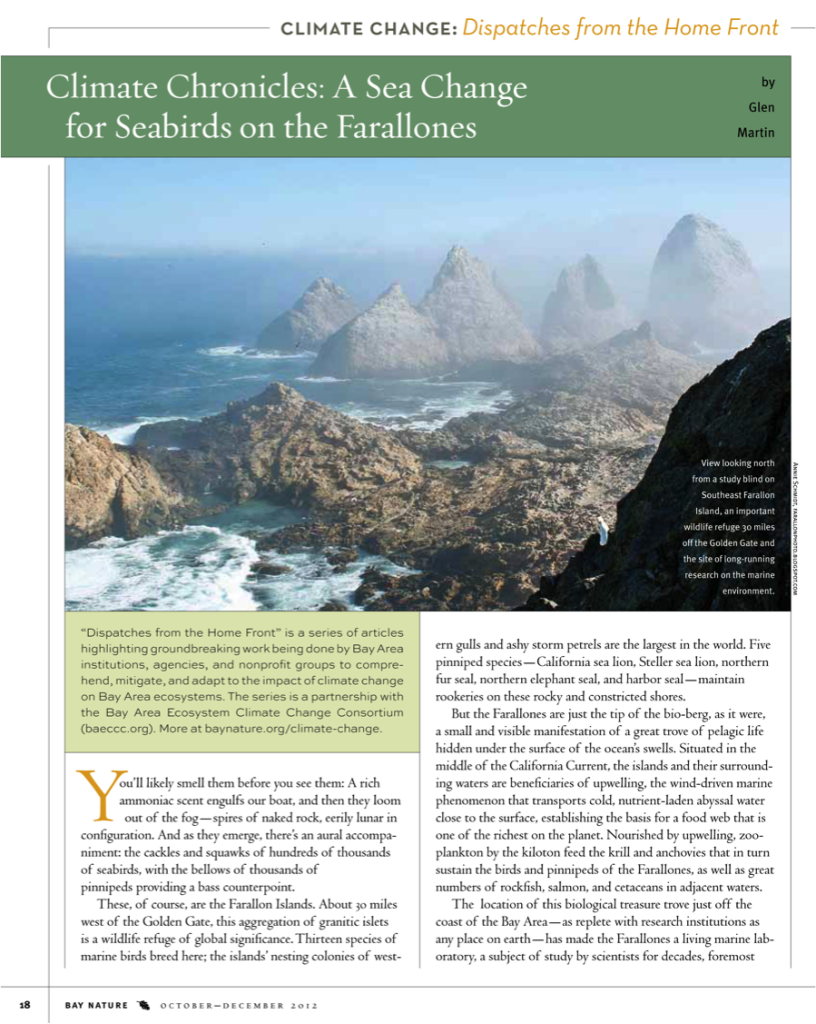

Or I go out on a boat to the Farallones where the ocean is alive with humpback whales and white-sided dolphins and sea lions and murres, and I’m transfixed by the vitality and abundance of nature so close to our shores, but mostly out of sight. We have the great fortune here in northern California to encounter natural beauty and wildlife almost any day of our lives. I’d love to share with you a recent experience from a weekend getaway to the Monterey Peninsula over the New Year’s holiday:

If you spend a certain amount of time outside in places with wildlife, these kinds of encounters can happen. Now, I should say that this is not necessarily a wonderful thing. I mean, it was exciting to have a close encounter with a sea otter, but once the animal had climbed up on the rear deck of my boat, I quickly realized that this was a tricky situation: First of all, I couldn’t see the otter without twisting all the way around and further unbalancing my boat. Secondly, I had no idea what it was going to do: Would it or bite me or perhaps even tip the boat over?

And finally, I had no idea how to get it off the boat. Fortunately, my girlfriend was nearby, and once she stopped laughing and taking pictures, she paddled over and was able to use her paddle to gently encourage him (or her) to slide off.

The other problem with this scene, of course, is that it’s not such a good thing for these wild animals to become so acclimated to humans. I consulted later with a couple of otter experts, and they said that while this kind of encounter is rare, it’s happening more than it used to. Sea otters are apparently just naturally curious, and as their collective memory of being slaughtered by humans fades away, and they become used to seeing people in kayaks acting in nonthreatening ways, they’re likely to engage in more of this kind of behavior. So it’s best not to encourage it, no matter how cute it looks.

[Watch the video “Man Meets Otter” to witness David’s fateful encounter. — Eds.]

So it’s experiences like these that remind me what we have here: ecosystems of surpassing beauty, and of tremendous biological and scenic diversity, persisting in one of the world’s most dynamic metropolitan areas. This is not something that we should take for granted.

So, part of what led me to start Bay Nature was simply the desire to share with others these kinds of experiences that have the potential to fill our senses and open our hearts. But there’s something deeper than that.

There’s also a piece that is about the importance of being connected to the place where you live, as both an end in itself and as an antidote to the fractured and disconnected nature of life in our crazy hyperdrive world. As I’ve worked on Bay Nature over this past decade and a half, and had the privilege of getting better acquainted with the landscapes of the Bay Area, I’ve become more convinced that we actually have the opportunity here to create a sustainable relationship between human and our natural ecosystems.

To me, this is the core question: Is there a way that humans can live on the planet, and in particular, live in the Bay Area, without overwhelming it. Can we share this biologically and ecologically blessed corner of the earth with the birds and fish and mammals and plants and rocks that were here long before we arrived and that define the character of this place? Or let me put it this way: I don’t think there IS a way we can survive on this planet over the long haul WITHOUT sharing it with these native ecosystems. So figuring out how to do that is where I think we need to put our energy.

And the first step in doing this is to acknowledge and recognize the actors and processes that make up the world we inhabit, to recognize and feel part of our own ecological niche. When we notice the ruby-crowned kinglets returning to our neighborhood trees in the fall; when we witness the return of coho salmon to the creeks of west Marin in early winter; or revel in an abundant display of shooting stars on a hillside in early spring; or welcome the haunting song of the Swainson’s Thrush in the woodland canopy in early summer, then we’re tuning in to the seasonal cycles of our homeland. By doing that, by identifying and recognizing these native species and their cycles, we connect to them, feel part of their lives and feel them to be part of ours. And we begin to feel a little bit more at home in our home, which they are sharing with us.

Of course, for good or ill, nowadays we no longer depend, as our predecessors did, on perceiving these seasonal signals from the natural world, and the resources they represented, to feed and clothe and house ourselves. We don’t depend on the local coho salmon to feed our families in winter, so perhaps it’s not important for us to be keyed into their annual spawning run in Lagunitas Creek. We don’t need to harvest and roast the delicious bulbs of the brodeiea in late summer or the acorns in late fall, to survive.

Instead, these days our children are more likely to be attuned to the sign of the Golden Arches than to the ripening of acorns on our native oaks. We are much more likely to recognize the logos of major corporations than we are the native plants and animals of our home base. And of course, that makes sense. Our food comes from Subway and Safeway, not from the Laguna de Santa Rosa.

But I don’t think that this severing of our physical dependence on these natural cues for our individual and collective survival has nullified our spiritual need for that connection, for a communion with our natural surroundings. Because ultimately, we DO still depend on the natural world and its resources for survival, even if we live much of our lives separated from that reality by many layers of plastic packaging and video screen images. And I think we ignore that fact at our peril.

As humans, we have the awesome power to disrupt those cycles of the natural world. But we don’t have the power to escape the consequences of disrupting them, at least not forever. Indeed, this severing of our connection, as a people, to the natural world has serious and far-reaching consequences. Climate change is Exhibit A.

Climate change is the predictable result of our practice of extracting carbon-based materials from the earth and processing them – mostly burning them – in a curious and clueless effort to continue growing and consuming in a clearly unsustainable fashion. And no one seems capable of hitting the stop button, or even the slow-down button, despite the incontrovertible evidence that the impacts are hitting us here and now, even here in the Bay Area, with our lovely moderate Mediterranean climate.

So here we are, facing a crying need for a complete transformation in how we operate on the planet, yet we have a political system so entrenched in the current way of doing things that it’s not able to respond to this very real crisis. Even after several years of extreme weather events, headlined by Superstorm Sandy, which brought New York City to a standstill more effectively than the 9/11 bombers could, we still can’t mobilize on a national level to confront climate change. We created a Department of Homeland Security, and even gave up some of our rights to privacy and free speech, in order to avoid a repetition of 9/11. But we’re apparently not willing to give up our rights to drive huge gas-guzzlers or create a department of climate stability in order to avoid a repeat of Sandy.

So what’s the role of a local nature magazine in the face of our species’ seemingly inexorable march to the proverbial edge of the existential cliff?

Back in 2003, Bay Nature published an essay by Greg Sarris, an excellent writer, but you probably know him as the controversial Tribal Chair of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, the tribe that built the huge new casino in Rohnert Park. But I know Greg as an author who speaks for the descendants of the Coast Miwok people, the original inhabitants of the areas we now call Marin and Sonoma. And if you don’t mind, I’ll stick to Greg the author and Greg the authority on indigenous culture of the Bay Area. In his 2003 essay for Bay Nature, Greg describes how the traditional Coast Miwok viewed the landscape as a network of places that were imbued with the stories of the people from the generations before them.

Right here might be the place where your grandmothers gathered grass seeds to be roasted and eaten; over there the place where the village would move every fall to gather the acorns that would sustain the people of the village through the winter; and there the place along the creek where your people awaited the returning salmon. Sarris asks us to imagine a map showing the lines between all these places, and he goes on, “Eventually there would be so many places and connecting lines that the map would finally look like a tightly woven, intricately designed Miwok basket. The patterns would circle around, endless, beautiful, so that the map would, in the end, designate the territory in its entirety… Each place, each person, you and me, the earth, water, and sky, inseparable, fully connected.”

I don’t want to romanticize Miwok culture: life was often pretty hard and individual life was not all that long; but there is no denying that the Miwok, and the Ohlone, Pomo, and Patwins around this region, had a good long track record of thriving as a people on this land base and keeping it healthy and productive over the course of 5,000 years or more. Something that we—with all our technology and enterprise—have not been able to replicate in the mere two and a half centuries since we arrived on the scene.

Indeed, if we were to try to replicate Sarris’ basket now, most of the lines connecting us to the resources our society depends on would have to reach all the way across the Pacific Ocean to China, and from there branch out again to mines in Sierra Leone and forests in Indonesia and oil fields in Ecuador’s Amazon region, and so on. So, yes, we are all connected, after a fashion, to the factory worker in Bangladesh and the bauxite miner in Guinea, but not in any sort of way that enriches our lives, or theirs, or the planet. Quite the contrary.

But Bay Nature is not about mourning what’s been lost or what’s gone wrong. It’s important to recall and recognize what was here before, without becoming immobilized by this sense of loss. Because in fact, the news isn’t all bad. That is where Bay Nature comes in. As I understand it, the Miwok gave meaningful names to all the features of their landscape and imbued them with stories as a way to pass on to succeeding generations the culture’s accumulated knowledge of those places and the precious, life-sustaining resources they embodied. Now, here in the Bay Area, we are again beginning to accumulate deep knowledge of the landscapes around us, and sufficient wisdom about how they work, to weave new stories for our peers and for our children.

This includes knowledge of the hydrology of watersheds like the Russian River. Knowledge of complex marsh systems on San Francisco Bay. Knowledge of these riparian areas and wetlands and how they sustain the health of fish and other aquatic species. Knowledge of our grasslands that allows us to promote the return of native grasses and the complex of native animals that depend on them.

Over the past fourteen years spent publishing Bay Nature, I have learned about many local citizen efforts directed at defending, protecting, learning about, and restoring nearby pieces of the landscape.

The big news is that, on the local level, we have largely moved from defense to offense, beyond just saving a few remaining outposts of the natural world, to learning how to restore both small pieces and even landscape-size chunks, like the South Bay salt ponds.

Look at the tremendous work being done by the urban creek restoration movement that actually started here in the Bay Area, and has become a force for change in both the landscape and in the communities that live alongside the creeks. Look at the superb work done on the restoration of meaningful biological function and aquatic life to the Napa River. Or right here in the Valley of the Moon, the ambitious project undertaken by the Sonoma Land Trust to reestablish the severed wildlife corridor from Sonoma Mountain across the valley floor to the Mayacamas.

And then multiply these initiatives by all of the native plant groups and open space organizations and trail groups and environmental education classes and the friends of this and that watershed, and you’ve got the makings of a dynamic and effective and sustainable movement.

Bay Nature’s small role in all of this is to seek out these promising initiatives, take this developing knowledge and these inspiring stories, and amplify them, spread them around, and help inform, nurture and sustain this growing community of people who are committed to reversing the process of our alienation from the planet, and to building a critical mass of people who are committed to reconnecting with it.

That basket that Greg Sarris was talking about – that imagined map of our home landscape – has become frayed and torn over the years; there are so many holes in it right now it can no longer hold grass seeds or acorn mush like it used to. But as we start to refill the landscape with our own stories of restoration and renewal, the basket can be repaired and refashioned, now with some designs of our own making, based on the work we’re doing in our watersheds and for our local parks and open spaces. We really do have a chance in the Bay Area to point our communities in a different direction and to serve as something of a model for other metropolitan areas around the country.

Bay Nature is fed by this movement, and we feed it in turn, by putting these experiences into words, assembling the words and related images into a product that is both beautiful and accessible, and sharing it with others, which hopefully inspires those who read it to explore their home landscapes and get involved in saving them.

I think it is that positive, inspiring, and attractive aspect of the magazine that has allowed it to find a receptive and loyal audience and has sustained it in an era when print publications are generally having a hard go of it. So for us at Bay Nature, there is no contradiction between recognizing and confronting the challenges we face as a species and a planet, and celebrating the beauty all around us. It is my hope that in being inspired by the beauty of the planet, we tap into the source of our conviction to keep it whole. And it is my firm belief that the best place to start is right here where we live.

Now, I do believe that every place on this earth is intrinsically beautiful. Or rather, I believe that the nature that underlies every place on earth is intrinsically beautiful. But natural forces have conspired to give Northern and Central California an especially large helping of both natural beauty and biological diversity. And trying to understand how and why that is true was the question I was grappling with when I came up with the idea of starting Bay Nature. In fact, I can recall the exact moment.

I had just left my previous job. I didn’t know what I wanted to do next, but I knew I was exhausted and needed some time off. And I knew that I wanted that time off to include taking hikes on weekdays, so I could find both beauty and solitude in nature.

So on a cold and clear winter morning, I went for a hike at China Camp State Park near San Rafael. It was a weekday and I had the trail pretty much to myself. Part way up to the top of the ridge, I took a seat under some oaks and madrones, and just listened and watched as a flock of small winter birds – chickadees, bushtits, kinglets, Townsend’s warblers – moved through the branches above, foraging for insects.

At the time, I didn’t know the names of all the birds and the trees, but I felt there was something uniquely Bay Area about this assemblage of plants, and this grouping of birds. I had lived here for almost a quarter of a century, and it was my home, so I had a “feel” for it. But I had been so busy with so many other things, I had never taken the time to find out who were these plants and animals that were sharing their home with me.

As a member of various national environmental organizations, I read the magazines of the Audubon Society and the Sierra Club and The Nature Conservancy. And in those pages I read about wonderful places and natural phenomena all over the world. But theyre all so far away. What if I wanted to learn about where I lived? Where was I going to turn for that? Well, I was newly unemployed, so why not turn to myself? And the rest, as they say, is history.

It took a while, but I did eventually come to learn through osmosis what it is that makes this region unique. As I said before, I’m not an expert, but from what I’ve learned over the past 14 years, I would say that the two major factors that have shaped the natural world of the Bay Area and produced its wealth of habitats and biological diversity are plate tectonics and the California Current. I’ll go ahead and say just a little about each.

The story of California is a rich and complex one, but geologically speaking, it’s not very old. Basically, not so very long ago, in geologic time, there was no “here here”. I.e. there was nothing here at this latitude and longitude but water; dry land was way off to the east.

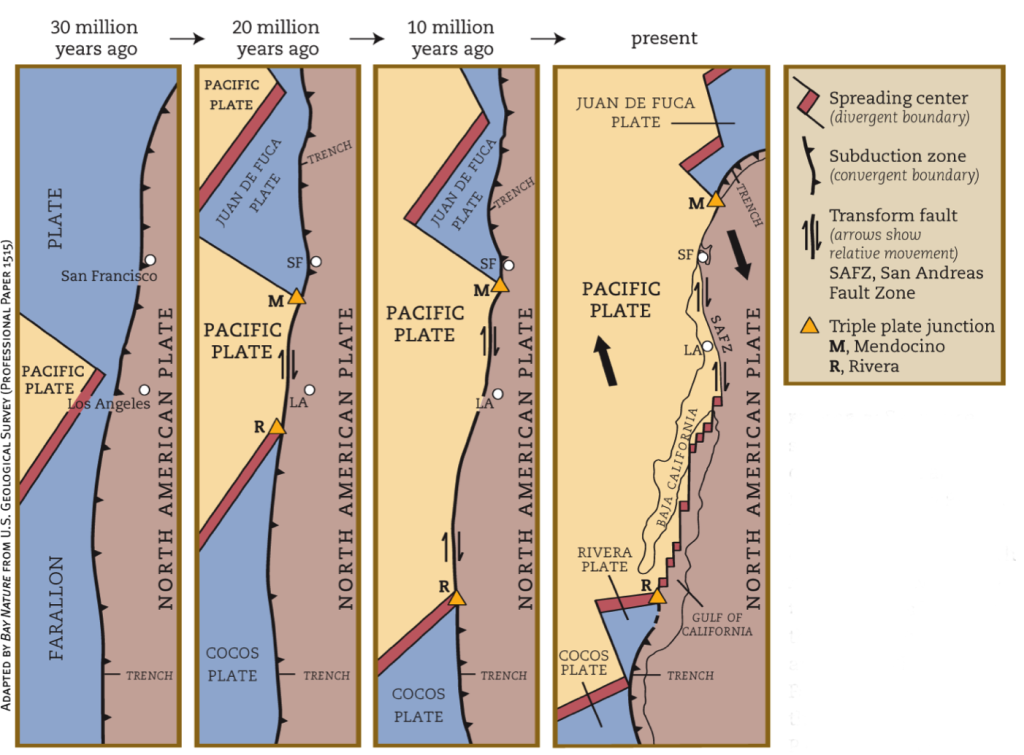

But due to movement of the massive plates that make up the earth’s crust, land was on the way in the form of the Farallon Plate, a chunk of oceanic crust that was moving eastward toward a larger piece of the continental crust we call the North American Plate .

Where the two plates came together, the leading edge of the oceanic Farallon Plate was forced down and under the contintintal crust, toward the earth’s mantle, where its rocks were subjected to intense heat and pressure, generating huge reservoirs of molten rock. Some of that rock found it’s way to the surface, emerging as lava and creating volcanoes. And some of it cooled and hardened underground, becoming granitic rock. That’s the story of the origins of the Sierra Nevada, related to our Bay Area story, but not where we want to focus.

So let’s go back up toward the surface, where some of the upper layer of this oceanic crust actually got scraped off in the collision and plastered on to the edge of the continental crust in a process of accretion. And that series of so-called “accretionary wedges” became the basis of much of the western part of what we call California.

Then, about 25 to 30 million years ago, the Farallon Plate had been completely consumed beneath the North American Plate, and a different plate – the Pacific Plate – took its place, at first to the south around where Baja California is now, but gradually moving north. Because this Pacific Plate, instead of moving directly east into the continent, moved more in a northerly direction. Which meant that the plate boundary was no longer a subduction zone, but rather a transform boundary, with the Pacific Plate moving north northwest relative to the North American. And the region between these two plates is what we call the San Andreas Fault zone.

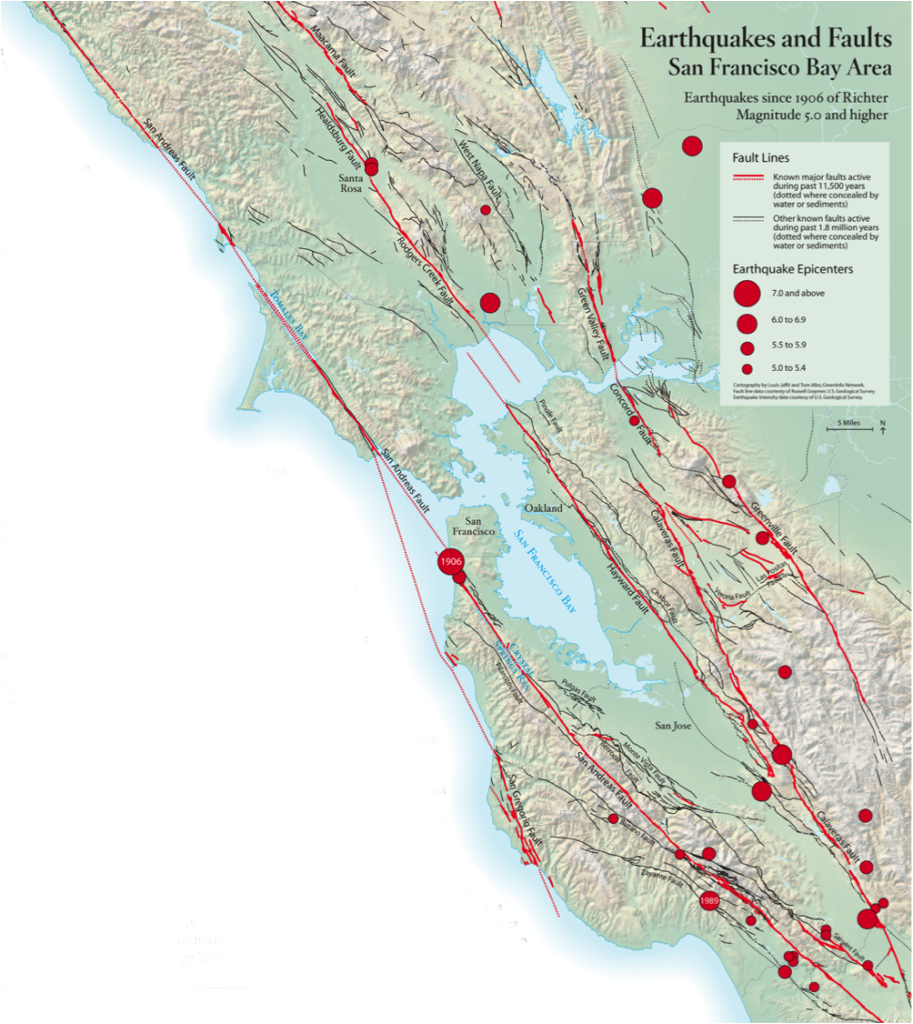

Now an important thing to keep in mind is that the San Andreas Fault is not a line in the earth; it is a zone. It’s tempting to look at a photo like this, taken near Olema in Point Reyes after the great 1906 earthquake and say, oh, look there’s the fault. But the rupture in the photo is just a surface expression of the actual fault much deeper underground and much grander in scale. The fault zone includes the Hayward Fault where I live in the East Bay, which becomes the Rodger’s Creek Fault up here in Sonoma.

This means that the pressures exerted by these two huge plates play out across the whole swath of our region as shown by the red dots on this map indicating historic earthquake event epicenters over the past 110 years.

Notice also on this map how all of the ridgelines and valleys follow this northwest-southeast angle that mirrors the faults. Keep that in mind as we introduce one last important piece of the puzzle. Because while the dominant motion between the plates of the San Andreas is transform, with the plates grinding past each other, about 3.5 million years ago, the motion started to change slightly, and the Pacific and North American plates began to collide at a slight angle instead of simply sliding past each other.

This combination of movements – transform combined with compression—is called transpression. Today about ten percent of the motion between the plates is compression. Geologists say that the similar to the rumples and folds you would see if you pushed on opposite edges of a tablecloth. And the result is this typically hilly topography of the Bay Area and its beautiful coast ranges, like you see in the view here of Pleasanton Ridge and Mount Diablo.

And the San Francisco Bay, the region’s central and signature physical feature, is of course also defined by these faults, bounded by the San Andreas to the west and the Hayward Fault to the east. It sits on what geologists call a “block” – that is, a piece of the earth that has been created by the stresses of tectonic motion – that has sunk relative to the surrounding landforms due the motion of the faults on either side of it.

And here is a view of the San Andreas Fault as expressed in the valley that is now filled by the Crystal Springs Reservoir just west of Highway 280.

So this is, in a very crude nutshell, the story of the shaping of the physical underpinnings of the Bay Area. So please hold on to the image of this varied and rumpled landform caused by plate tectonics, and we’ll turn our attention briefly to that other major phenomenon, the ocean upwelling associated with the California Current.

I’ll start this piece with a personal story. I first came to California on a summer vacation with my parents in 1965, when I was 14 years old. We lived in New York, and I had only been west of the Mississippi once before that, a classic Southwest trip to the Grand Canyon and Mesa Verde. From that first eye-opening trip, I had become a huge fan of dramatic landscapes, and I was especially looking forward to the drive up from Los Angeles to San Francisco, along the ocean on Route One. But as longtime California residents, you can probably guess what happened. I could HEAR the ocean, but seeing it was another matter. The route all the way up the coast was shrouded in heavy fog. Where was this sunny california I had heard so much about? Of course, what I was experiencing was our summer fog, the result of the California Current and the phenomenon known as upwelling.

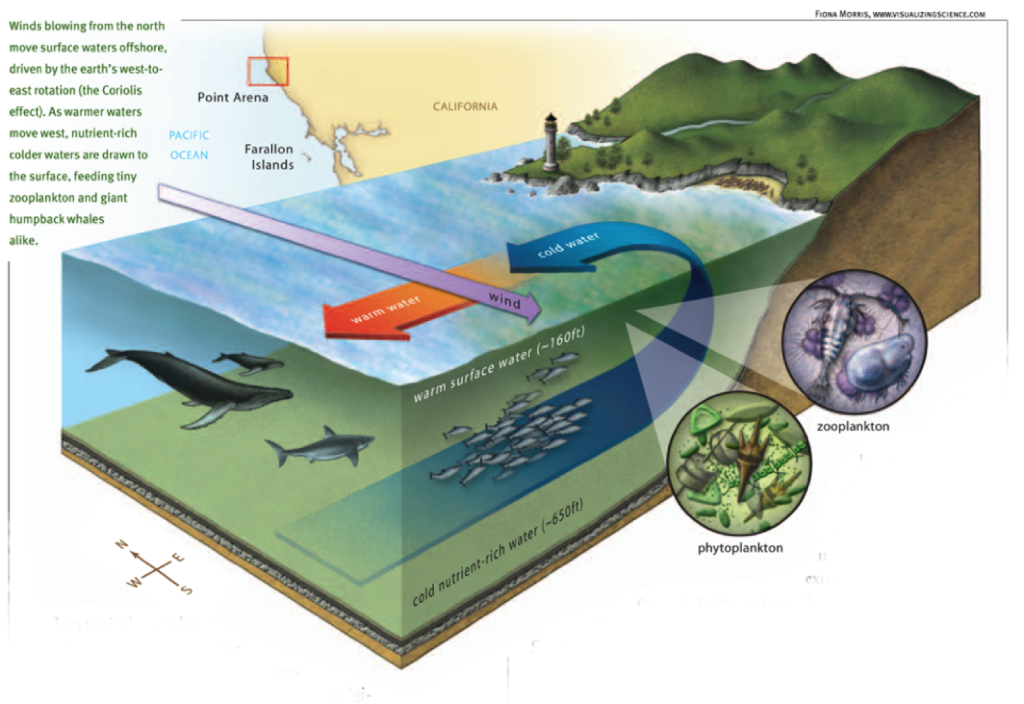

This graphic produced for Bay Nature shows the basic operation in a schematic fashion. But basically, prevailing summer winds driven by changes in atmospheric pressure blow down from Alaska and due to the direction of the earth’s rotation, the winds cause the warmer water at the surface of the ocean near the coast to be blown offshore, which in turn, causes colder water from below to rise to the surface, bringing with it all sorts of nutrients that form the base of one of the richest ecosystems on the planet,

attracting everything from sardines and rockfish to white sharks and blue whales, and all of those birds and marine mammals that you see breeding out on the Farallones if you are fortunate enough to take the boat ride out there.

But of course, the upwelling doesn’t only impact on the marine ecosystem. It also creates that fog I encountered back in 1965. When that cold upwelled water meets the warm summer air, it condenses and forms the fog that gets sucked inland toward the low pressure zone created by the baking heat in the Central Valley.

So now we have the combination of the tectonically-produced hill and valley topography and a dynamic climate of fog from the west dueling with the hot dry interior, and you get the famous Bay Area microclimates. Where the temperature gradient on a summer day can go from 55 degrees at Ocean Beach to 95 degrees in Concord. And if you’re in between, well, who knows? And ergo the famous admonition from hike leaders to their participants almost any time of year in the Bay Area: Dress in layers!

And of course, even when it’s not foggy, the cool ocean waters provide a significant moderating effect on temperatures, and so we live in one of the most temperate areas on the planet – not too hot in the summer, not too cold in the winter.

And this combination of factors is not only great for humans; it’s also great for plants and animals, for biodiversity, because it produces such a variety of livable habitat types within such a small area. From the lush old growth redwoods of Muir Woods and Big Basin to the west, to the dry chaparral of Mount Diablo.

At China Camp State Park where I had my epiphany for Bay Nature, you park your car next to a natural tidal marsh ecosystem, then you climb up the hill through a lovely mixed hardwood forest with three kinds of oaks as well as madrone and bay and buckeye and maple trees. And then, near the top of the ridge, you can drop down into a small protected creek corridor that is lined with redwood trees.

And if you follow a side trail through these redwoods, you emerge on to the south side of the ridge into a sunny chaparral zone populated by manzanitas. All of this within about three miles. It’s this type of habitat diversity that gives us 10 species of oaks in the nine-county Bay Area and 33 species of manzanita – 19 of them found ONLY here.

The irony here is that two of the factors that many consider to be downsides of living in the Bay Area – summer fog and earthquakes – are at the same time the two main factors that make the Bay Area such a wonderful and attractive place to live, for humans and for all manner of flora and fauna.

So is that the end of the story? Of course not. Nature is – by nature – always dynamic and always changing. As you well know, we could have one of those aforementioned earthquakes tomorrow, which could cause extensive damage and devastation to our regional infrastructure. But it wouldn’t actually have much impact on our natural ecosystems, unless we all decided to go camp out under the trees instead of rebuilding our homes. Eventually, of course, over the next several millenia, Point Reyes — where these elk live — will move north relative to Santa Rosa, and Santa Rosa will move north relative to Concord, but that is well within the natural order of things here in an active tectonic zone.

But there is a source of change that is outside the natural order of things and that is moving a lot faster than the pace of evolution. And that, of course, is climate change.

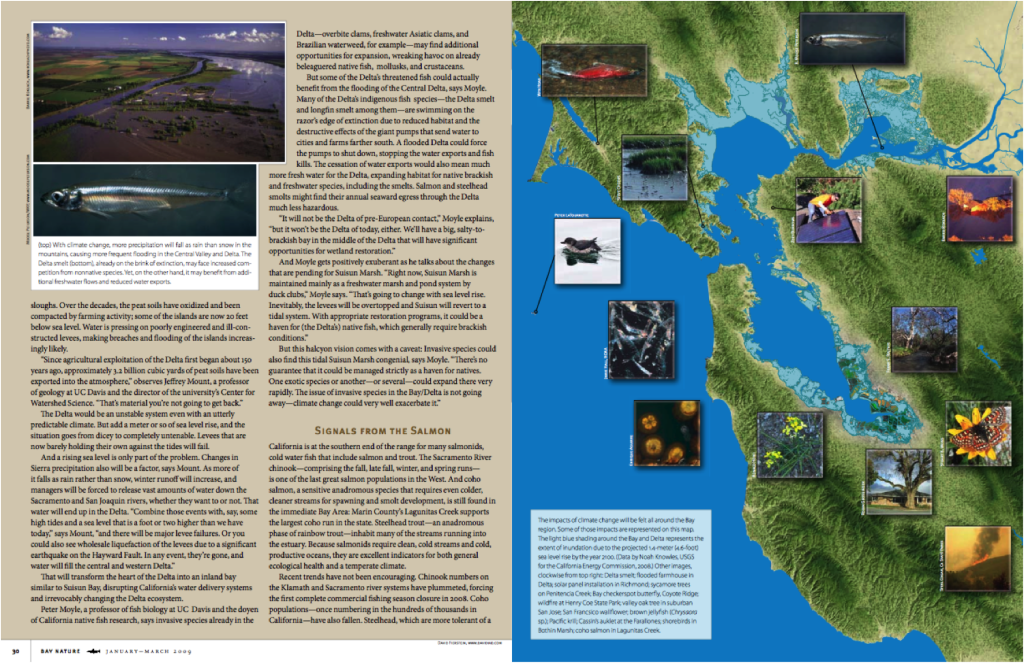

So how will climate change impact our local ecosystems? At Bay Nature, we made a valiant attempt at a first pass at that question, in this special section published in 2009,

where we did a broad overview of the relatively new science of downscaling global climate change models to the regional and local levels. Which of course, makes eminent sense, since most of us are not going to notice the disappearance of polar ice and polar bears in our daily lives. But we are going to start noticing the super high tides and storm surges in San Francisco Bay.

There are a few things we know for sure about climate change:

– Temperatures globally will rise;

– Sea level will rise;

– And the ocean will become warmer and more acidic.

But understanding how these factors will interact with one another and with the specific climate and microclimates of each region is less well understood.

We know, for instance, that ocean upwelling has been extremely uneven in recent years, almost completely shutting down in 2006-07, leading to massive nest failures for this bird here, the Cassin’s Auklet, which nests on the Farallones.

A couple of years later, upwelling returned, and in recent years we’ve seen great abundance of some key prey species, but not others. So rather than consistent patterns, what we see increasingly is wider swings, which leads to the prediction that what we’re going to experience is not so much a straight path to fire and brimstone as increasing unpredictability, often accompanied by greater extremes in the weather, like the record drought we’re experiencing here this year, while the Northeast and Midwest deal with record cold and snowfall, and England suffers historic floodng. And it is likely that here in California we will see BOTH increasingly severe droughts AND more destructive flooding.

One key question for us in Northern California is how the changes in the ocean and in the atmosphere will affect the formation of fog, such a key component of our ecosystem, as discussed earlier. This question has major implications for both our landscapes and our economy. So the work on figuring it out is important, and fortunately, already underway.

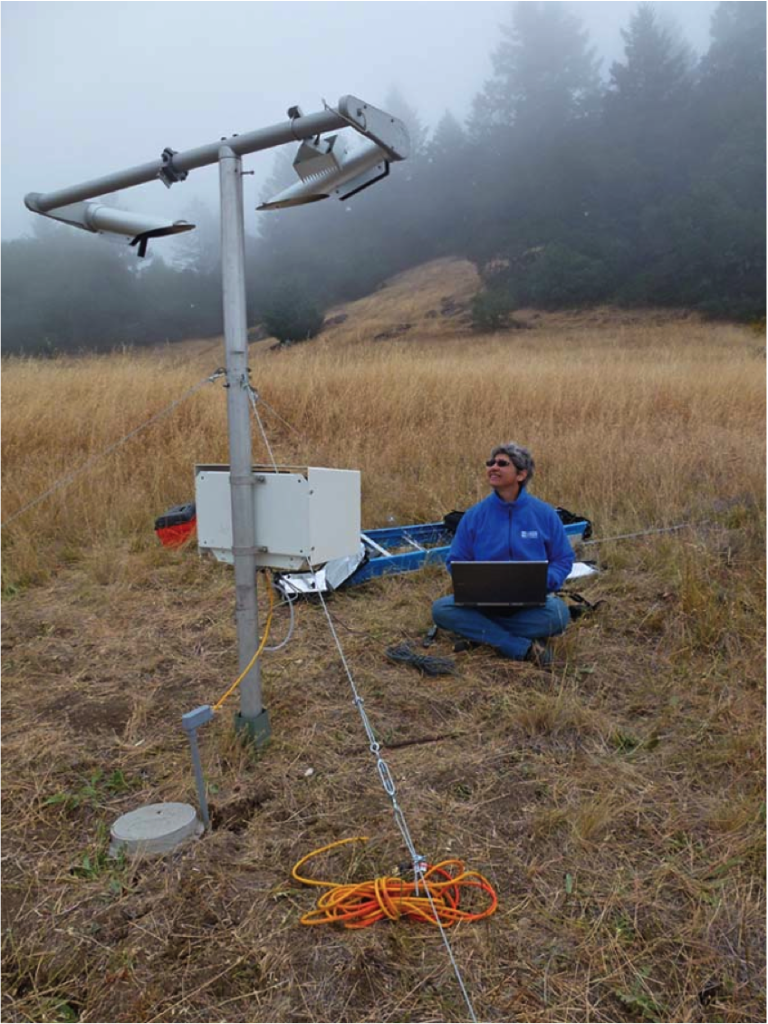

A few summers ago, some bright and intrepid scientists donned their climbing gear and worked they way up to the tops of some of tallest redwoods to actually measure the droplets of fog that get harvested by redwood needles. At the same time, other scientists were back in the lab, studying core samples taken from living redwoods to get a better handle on the historical record of fog and rain in the redwood forest. And simultaneously, scientists were setting up fog monitors at Pepperwood Preserve just a few miles from here, to correlate data between fog on the coast and fog further inland, in the coast range.

The outcome of this research will help us figure out what’s in store for us in a time of climate change and help us plan for it.

It is these examples of ingenuity and determination involving engaged and dedicated people that led us at Bay Nature to decide to add a regular feature article about climate change research and impacts to each issue of the magazine.

It’s not that we feel we need to convince our readers that climate change is real and happening here and now. I’m pretty sure they get that. It’s more that we want to transform the perception of this issue from one that is overwhelming and paralyzing to one that is being addressed in novel and imaginative ways by some of our best and brightest thinkers and scientists. By broadcasting these stories beyond the narrow boundaries of the scientific research and policy advocacy communities, we hope to build support for the long term investment and research that will be needed to get a handle on climate change impacts, and then figure out the best ways for our communities—both human and natural–to survive and thrive in an era of climate change in our still beautiful and beloved Bay Area.

So that’s a very broad and superficial look at the major factors shaping our local ecosystems. I’m going to stop here and hope that I will have at least sparked some interest in this topic and in Bay Nature magazine, which is committed to addressing these issues while at the same having a lot of fun exploring our rich and diverse natural landscapes. If you’re interested in learning more about the magazine, I urge you to take a look at some of the copies I have displayed on the table at the back, and even buy one or more to take home and read, or maybe even subscribe and get the next four issues sent directly to your mailbox. It will help keep Bay Nature going strong, and it will in turn, help YOU keep going strong as well!

Thanks for your kind attention and interest. I look forward to your questions.”

>> Find out more about Bay Nature magazine and subscribe here.