“Lines on a map have consequences…”

Como será un mundo sin fronteras

Que por dentro y por afuera

Es libre

Sin la expectativa

De que esta vida

Exista bajo cualquier constricción

De líneas

O muros limitando la imaginación

Sin el estrangulamiento

Del pensamiento

Que pone enfrente fronteras

Por dentro y por fuera

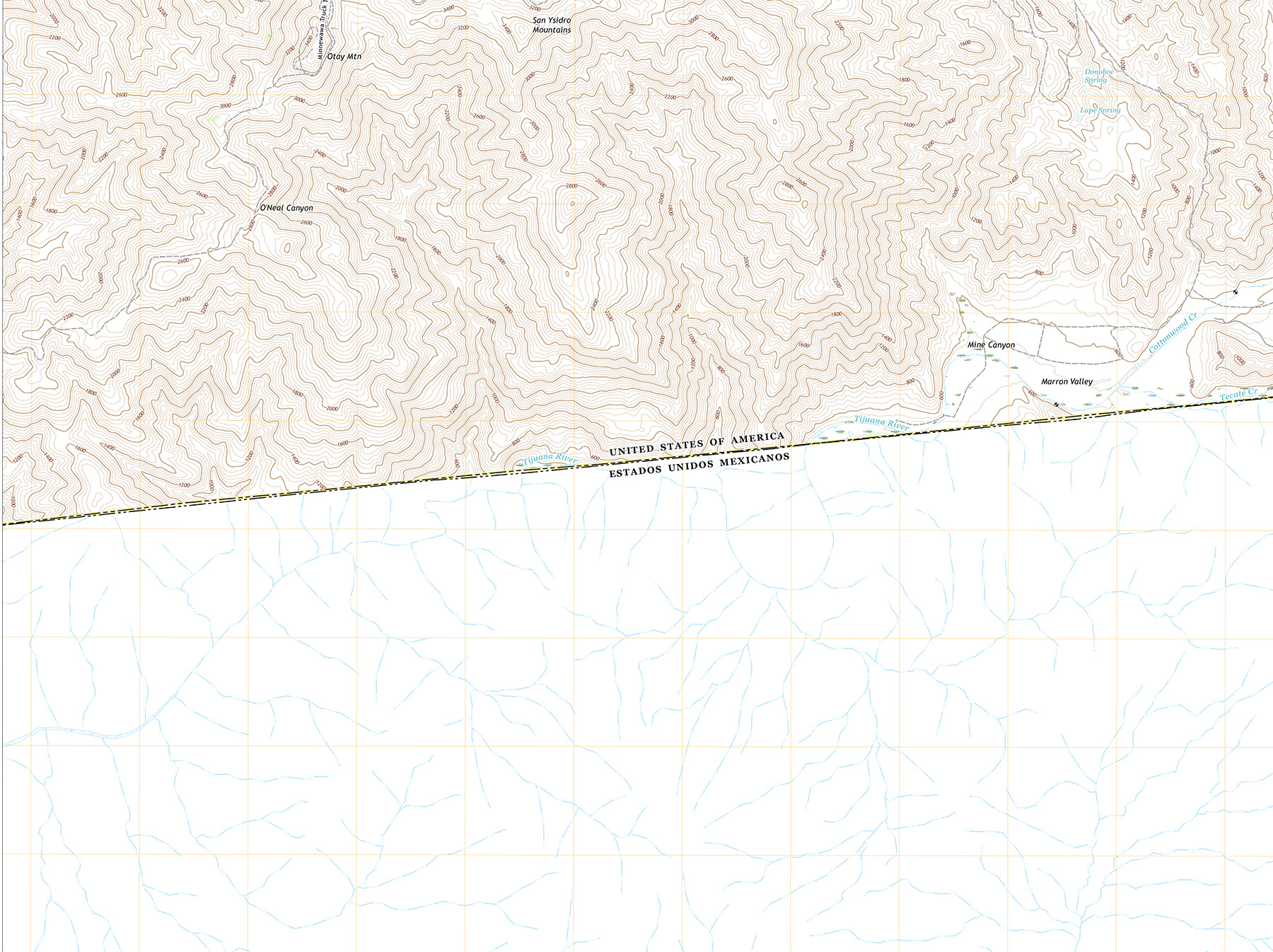

I first heard that line as a history student in reference to the the Sykes-Picot Agreement and other colonial decisions and their effects in the Middle East. But of late it has proved to be useful to me as a point of reference in thinking about the outdoors and conservation.

In college, a group of friends and I founded a teatro arte group, SEMILLA, as an outlet for the many creative ideas we could not necessarily channel through other student groups. We were active in M.E.Ch.A, and many of our themes related to immigration, labor practices, cultural identity, Chicanismo and other relevant community topics. But since I also was active in CALPirg, I usually brought the “nature outdoorsy” themes to our work.

One time we devised a play on immigration and the United States-Mexico border. I proposed we use wildlife as characters to illustrate patrolling borders like we did with people. We had a bear who was stopped at the border of a national park by law enforcement rangers, a migrating flock of birds stopped mid-flight by jets and helicopters, and turtles and dolphins stopped at sea.

In one of my most uncomfortable and memorable roles, I played the law enforcement ranger detaining a bear for crossing over a national park border without proper documentation and permission. I clearly remember an audience member standing up and yelling at me, “Hey man, let the bear through, he just wants to get some food!” Suffice to say, the line resonated.

It’s been many years since I’ve done that play, but I think of it now every time I use the quote — “lines on a map have consequences.” As I’ve worked longer in conservation, and introduced more people to outdoor parks, I’ve started to see two diverging ways of seeing lines on a map, and one bigger point.

The first way to see lines is when I talk about orientation, and we look at maps for navigation for outdoor trip planning and outings with families and community groups. It’s literally about understanding what the lines on a map mean so we can have a safe and enjoyable outdoor experience. We look at trail lines, distances, and directions. We joke about paying attention to contour lines because of the consequences of “those squiggly lines” for the enjoyment of our hike — “Oh look, it’s a really short hike through these squiggly lines all together.” I want our communities to have access to this information, to feel there isn’t a barrier between them and the knowledge and understanding that they too can be out here safe and aware. To know sin fronteras.

The second is when we talk about policy and how “people choices” matter when we decide what “is protected, why, and what for” as we go out on a hike. For participants on our hikes it may be the first time they’re hiking at a preserve, and they’re curious what’s the difference between that and an experience at a municipal park. Or when we begin to talk about the similarities and differences among national parks, regional parks, open space districts, national monuments, and other public lands. Part of the “Find Your Park” campaign for the 2016 National Park Service Centennial was to encourage people to visit their public lands regardless of which one, so it wouldn’t be limited just to national parks. It was to encourage people to go out and recreate in a diversity of public lands that could be managed by the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and even the Army Corps of Engineers.

But of course they are not actually all the same. Although in many cases we do not see the management lines out in the natural linescape (unless there is a clear fence of sorts) they are certainly there on maps, clearly noting management and stewardship authority. Here in the Bay Area, there are areas we can hop on the trail and hike through several different “types of parks.” And these lines do matter. They have consequences in terms of how resources are allocated, how they are funded, and even how people can access them.

Collaborative management is increasing in the Bay Area and other regions, with the North Bay’s One Tam project offering a clear example. This is important because although lines on a map help in managing people access, we do need the increasing awareness that wildlife “is not going to stop at the border.” Nor does drought, air pollution, or wildfires.

Which leads to the bigger point that I’ve been thinking about now. Thinking strictly about “conservation” I saw the importance and value of wildlife migration, habitat connectivity, and ecosystem connection. We stressed the importance of knowing that although we had lines on a map, we had to increasingly look at how wildlife could move “sin fronteras,” to be aware of how we were restricting nature with boundaries. Yet at the same time we might have missed opportunities for relevancy with marginalized communities.

In my early presentations I would present two migration charts showing movement between the United States and Mexico. One was a migration map that was fairly easily recognizable to conservation professionals and most would guess correctly when I asked what migration was being represented. The answer: monarch butterflies.

The second one would be a little harder, and although there were some correct guesses every now and then, generally many would not guess that it was a map of human migration: farmworkers. I would point out how in many cases we know more about the migration connectivity for wildlife than the migration connectivity for humans. Or even more directly how we extolled urgency to protect the honeybees as pollinators due to our dependence on them for many of our food sources, without consideration for the human labor often found in the same orchards, and with as much an impact on whether our food made it to the supermarket shelves. I wanted the conservation community and my Latinx community (and internally my respective identities) to work and understand each other sin fronteras, without preconceived boundaries.

I return to the idea that lines on a map have consequences, and that they will continue to indicate and dictate what is valued, why it’s important, why we care, and what we do about it — but it is we people that put them there.

Ultimately, that’s why we pay attention to the lines in the second case — because of what they reflect about the society and culture that drew them — not just the fact that we drew them but why and for what purpose. We’re wrestling right now with what our society and our culture should look like, and that means we’re wrestling right now with what the next lines will look like. The question I think out loud for you to ponder or respond to as well: how do we sustain these lines with consequences in mind, but also knowing that an increasingly changing and complex world requires us to think about what a world sin fronteras, without borders, looks like for the benefit of people, the flora, the fauna, the land and all in between? I know the importance of designating landscapes as “wilderness” to “save it” and the value of places receiving national monument status to ensure greater protection. Yet few places are free from human impact — or rather from negative impact. As more places need less negative human impact they are in need of positive impact in the form of awareness, support, resources, and protection. Which goes back to the need for an increasing diverse population to sustain engagement with this work — and the importance of valuing the interconnectedness of their issues with those of traditional mainstream conservation.

As you think about the parallels and interconnection between human and wildlife migration, and the impact of the border wall on both, think about how the continued and increasing threat of climate change forces us all to think “outside the lines.” Lines on a map have consequences and they’ll continue to do so. I continue to wonder what consequences we’ll have on those lines and what consequence those lines will have on us.