I must admit now, at the outset of this review of a book of poetry, that I have never read a book of poetry all the way through. And certainly not a 400-plus page anthology like Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California, which contains 264 poems about the landforms and waterbodies, flora and fauna, of the Golden State, all of which I read in a marathon two-day session (a result, I also admit, of overpromising on my deadlines). I began already convinced that I was going about this all wrong: that poetry should be dipped into and savored slowly, not plowed through like a supermarket stand novel. But by the end of those two days I felt like I had staggered out of a weeklong meditation retreat— I went about my daily life dazed, achingly conscious of the present moment and my emotions and just how fleeting everything really is. It was great.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

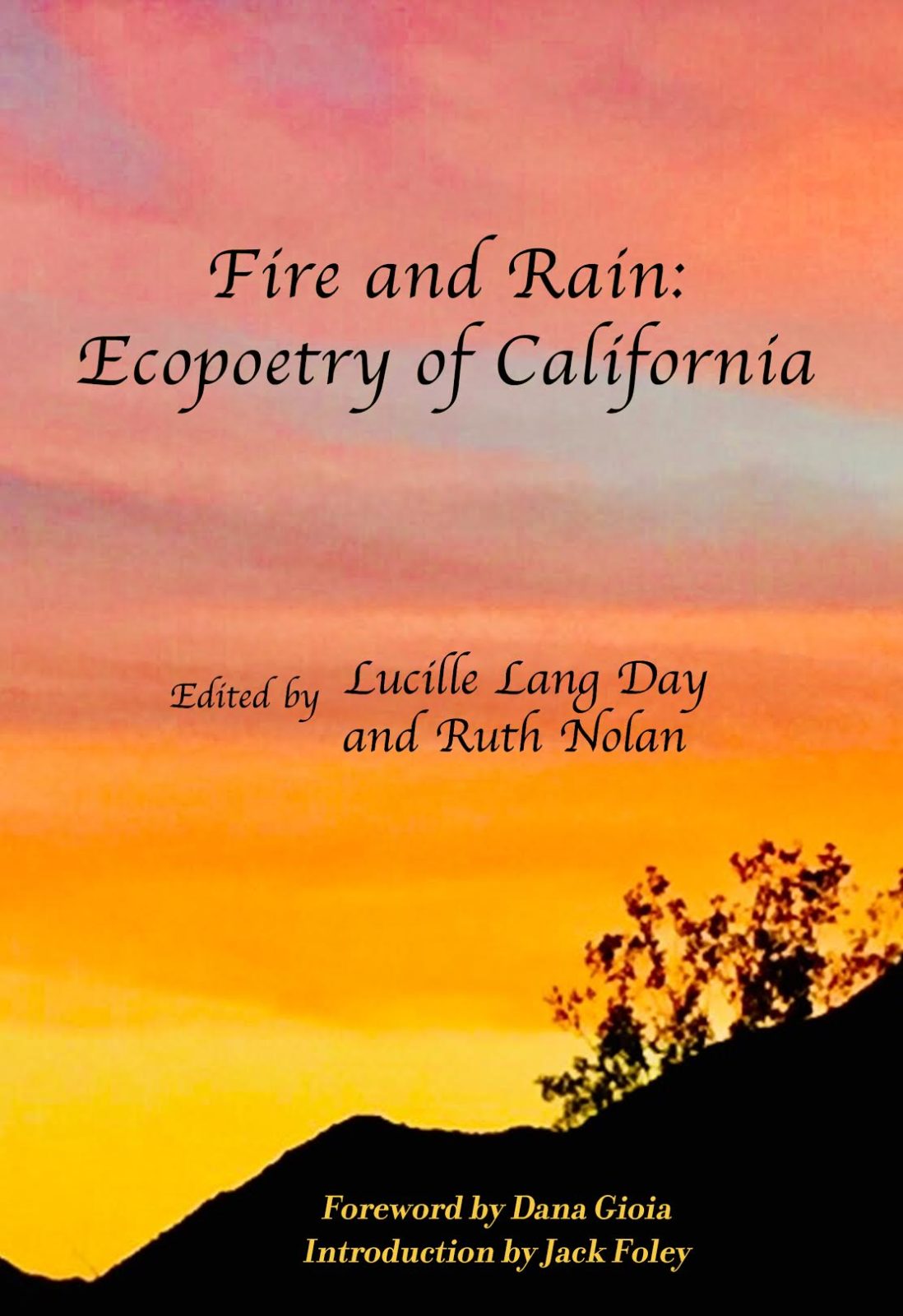

Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California

edited by Lucille Lang Day and Ruth Nolan

462 pp, Scarlet Tanager Books, October 2018

$25.00

Because it struck me, early on, that the sort of mental process poetry asks of its practitioners is the same one that occurs when we humans go out in nature, the same act of brief but attentive focus on sensory perception. The poems in Fire and Rain pay attention to the way flowers bloom (“heat instigates/jacaranda explosions,” writes Trina Gaynon in “Landscapes: San Fernando Valley”) or the way a flock of shorebirds moves (in “Credo,” Susan Cohen describes “How they swing over the water/this way and that,/a loose boom of birds, flare/right or snap left—visible,/golden, invisible, as sun catches/or releases them all—”), or even just the impact of a color, as Karen Greenbaum-Maya finds in “Long Lake Blues”: “So obvious, my discovery:/postcard Mediterranean/and glacier deeps/light up the same blue.” In the volume’s foreword, former California Poet Laureate Dana Gioia writes, “Poetry is a way of articulating reality, not an expression of power.” And there’s deep joy in articulating reality, the poems in the collection make clear—the simple reward of seeing the world as it is.

Even in its structure, the anthology seeks to mirror the lay of California’s vast, varied land. Its eight sections are each dedicated to a particular environment, from the coast and ocean to the Sierras, coastal redwoods, the Central Valley, and even “Cities, Towns, and Roads.” The groupings, sequenced by editors Lucille Lang Day and Ruth Nolan, create intriguing resonances—moods emerge. The ocean encourages wistful reminiscences of lost love, redwoods provoke a sort of bottomless yawning sorrow, “Hills and Canyons” call forth meditations on history, identity and home. It’s surprising and a little comforting to find that we humans are all jointly shaped, in some oblique but specific way, by our surroundings. And where we live can reflect who we are. Just look at “The High Desert,” an alluringly muscular paragraph of a poem by Nancy Schimmel, which begins: “Honey, I know a thing or two about the desert. …I know there’s more to the desert than you can see driving through. I like rocks, and the desert has good ones, and you can see them from your car window if you feel like looking, but if you get out of your damn car you’ll see that there are people and critters that live here.” Reading Fire and Rain is like touring the state with a host of extremely invested tour guides, showing us things in corners that we wouldn’t normally get to see. “The flowers out here ain’t roses, they are cactus flowers, prettier than roses or lilies, bold and tough like flowers should be, no wimps.”

But the collection could have been slimmer and preserved this far-flung chorus without its weaker poems, which tended to note surface-level descriptions of an experience in nature without textual surprise or deeper insight. And climate change, which hangs over the collection like a carbon dioxide-laden sky, offers up the challenge of transmitting grief and anger without getting overly literal. “It’s the final death underway,/species loss due to climate/change—too much heat,/too little rain, choking smog./There’s no debate—science/claims most desert forests/will succumb in this century,/that nothing can be done,” Cynthia Anderson writes in “Joshua Tree Weeping.” I prefer the threat of overflowing, engulfing waters at the end of Susan Kelly-DeWitt’s “Flood Plain”: “Time/to grow gills or gull wings, walker—/learn the jackknife, half-twist, pike.”

The book includes a fair share of luminaries: Ursula K. Le Guin, Gary Snyder, Jane Hirshfield, and a surprising number of current or former poet laureates of various California localities, including Sonoma County, Marin County (two of them!), Ventura County, and Berkeley. But many of the poets whose poems I liked best I knew nothing about. What drew me instead was their careful observation of nature, and the lessons they drew about its harshness, its beauty, and its total disinterest in the lives of us puny humans. In “Ode to the Brown Pelican” Susan Cohen writes, “Your eye is not a bird’s/obsidian bead/that bounces off me/like a ball bearing,/but sky-blue and fetching,/an eye that could meet mine/across a pillow or a café table/if we ever came nose to nose,/which is unlikely.” The poem indulges our attraction to animals, the way we anthropomorphize them, but also deflates it—wild animals are utterly remote.

Ken Haas’s “Birthday Poem” starts, “This year’s has fallen/on the day heaped snow/is slipping wholesale from pines/by dint of earth’s mood and spin,/as when something that is meant/to happen sometime/happens now”—lines that draw a link between our calendar dates, aging, and nature’s progression in general: they’re all arbitrary, depending on “earth’s mood.” And in “Golden Hills of California,” Cohen nails the quandary of enjoying the way sunlight filters through wildfire smoke:

This light began in lamentation,

but I don’t want to think

about the unmaking, the burning

hopes and homes a hundred miles

from here…

… In the fabled state

we live in, somewhere always is on fire—

dry grasses torching, shingles searing,

latches melting, miles of forest

reduced to the single syllable of ash—

while elsewhere that combustion blends

light and gold we can savor like wine,

which also begins with crushing.

“I live here/I wonder if a thousand/Is too many times to say/The same thing/I live here,” poet Patty Joslyn writes of the Mendocino coast. Fire and Rain is more than a hundred Californians affirming, in so many ways, the same thing.