Gary Williams first spotted Chromoplexaura cordellbankensis, a new species of deep-sea coral, in 2017. Williams was on a boat 50 miles northwest of San Francisco in the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, peering through the eyes of a robot gliding through the icy darkness 300 feet below the surface. The coral is yellow and about the size of a large hairpin. Yet even though this hairpin and several dozen others like it grew on a dark rock in a dark ocean surrounded by a tangle of other life, Williams’s brain registered it immediately as something he hadn’t seen before. “You don’t say it’s new,” Williams said recently. “You say, ‘I don’t recognize it.’”

The ROV operators tried to collect a sample, but couldn’t. So a year later Williams and other scientists returned to the same spot with a different ROV, found the rocky outcropping, found the coral, and clipped off an inch-long piece of arm to study. Under a microscope it turned out that it was a coral — they hadn’t been entirely certain of that — and also that it was in fact new. Williams, a curator of invertebrate zoology and geology at the California Academy of Sciences, and University of Costa Rica deep-sea coral expert Odalisca Breedy announced the discovery on May 15, 2019 in the Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. They chose to name the coral after the place it was found: Cordell Bank, a 26-square-mile rocky seamount that rises from the outer edge of the continental shelf west of Point Reyes. Since they identified the first one, however, the coral has been seen in three other places in California — in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, and in Cortes Bank, a seamount off the coast of San Diego.

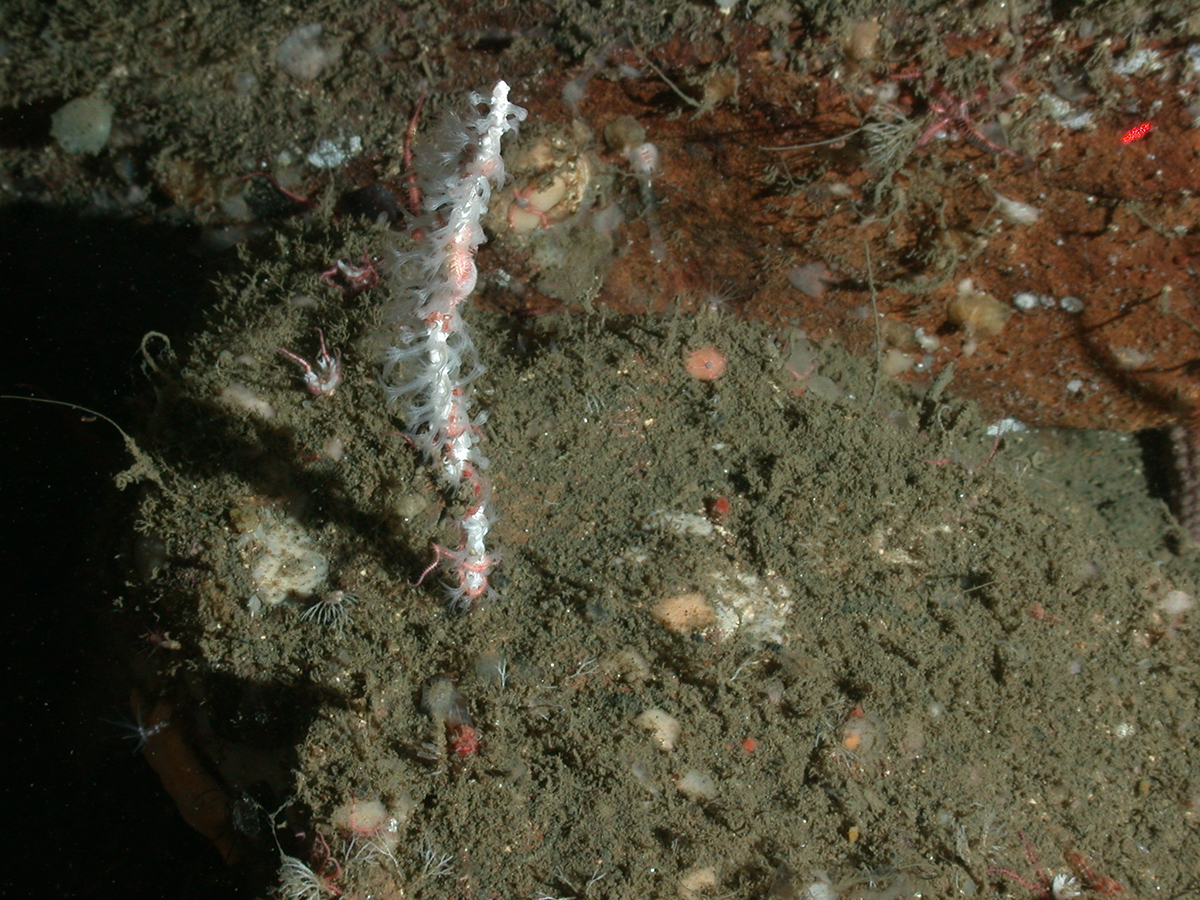

Chromoplexaura cordellbankensis is the second new coral species in the last five years that Williams has discovered and named from the deep sea west of the San Francisco Bay Area. The first, a kind of coral known as a “sea whip” that Williams named Swiftia farallonesica, was found in 2014 on a similar ROV cruise through the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

There is potentially much more to discover. Deep-sea corals, like the habitat where they live, are not well understood or described. Both new California corals seem limited to a few specific areas within the sanctuaries, though they’re common where they live, meaning even small unexplored places could be harboring new life. And working far below the surface, in the dark, with expensive technology, discoveries come slowly. “It’s like if you have an iceberg and you look at a square centimeter,” Williams said. “The ROV is very restricted in what it sees. You make a transect, and it’s what, a meter wide? And the ocean is how big?”

Nonetheless, the discoveries are coming faster with new technology. Until five years ago most knowledge of the corals of the Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones sanctuaries was based on scuba dives around Cordell Bank itself, which in places reaches within 115 feet of the surface, or on the accounts of scientists who’d dredged the bottom, or from fishermen who’d pulled something up from the deep and were curious enough to report it. Now repeated expeditions using remote underwater exploration vehicles and HD cameras have begun to fill in the gaps. The 2017 cruise by the Ocean Exploration Trust’s research boat E/V Nautilus, on which Williams first spotted Chromplexaura cordellbankensis, recorded 21 species of corals in the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, 16 of which hadn’t been seen in the sanctuary boundaries before.

It even turned out scientists had spotted Chromoplexaura cordellbankensis in the sanctuary before — they just didn’t recognize it. Crewed submersibles had traveled over the area and captured seafloor video with the species in it in the early 2000s. But in standard definition, says Cordell Bank NMS research contractor Kaitlin Graiff, the tiny Chromoplexaura were too grainy to stand out.

Corals, and particularly deep-sea corals, have long puzzled taxonomists. For centuries western naturalists classified corals into a group of living things called zoophytes, which quite literally meant “animal plants.” This is because, for most of their taxonomic history beginning with the corals first pulled from the Mediterranean Sea in the age of Aristotle, people had no idea what the things were. Picture this giant red-dripping branch, and all these philosophers gawking at it. First someone said, “It’s a mineral,” and then someone else said, “It’s a vegetable,” and then someone else said, “It’s an animal,” and then Pliny the Elder said, “It’s neither!” and then someone copied Pliny except the opposite and said, “It’s both.” (This dialogue took about 2,000 years.)

Of course the idea that this was some hybrid animal-plant or plant-mineral or whatever turned out to be inaccurate, too. With the advent of the microscope scientists looked close and saw … just animals, after all, but very strange ones.

The 5,450 known species of coral can be split several different ways, but most helpful, perhaps, is to divide them into reef-builders and free-livers. The reef-builders, the ones you think about when you think of sun-dappled tropical corals, make up just 15 percent of known species.

Two close relatives of reef-builders, the black corals and cup corals, have given up urban planning and wandered out of the warmth to live solitary lives in the darkness of the West Coast marine sanctuaries. A black coral known as Christmas tree coral, for example, lives at Cochrane Bank in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, 41 miles west of San Francisco, in what Greater Farallones NMS research coordinator Jan Roletto said is its northernmost known colony. The coral grows six feet tall and four feet wide and might be several hundred years old, Roletto said. A different species of black coral has formed colonies along the steep walls of a place nearby called the Farallons Escarpment that are so spectacular that Roletto said NOAA has worked with the Pacific Fisheries Management Council to try to stop bottom trawling in those regions to protect the corals.

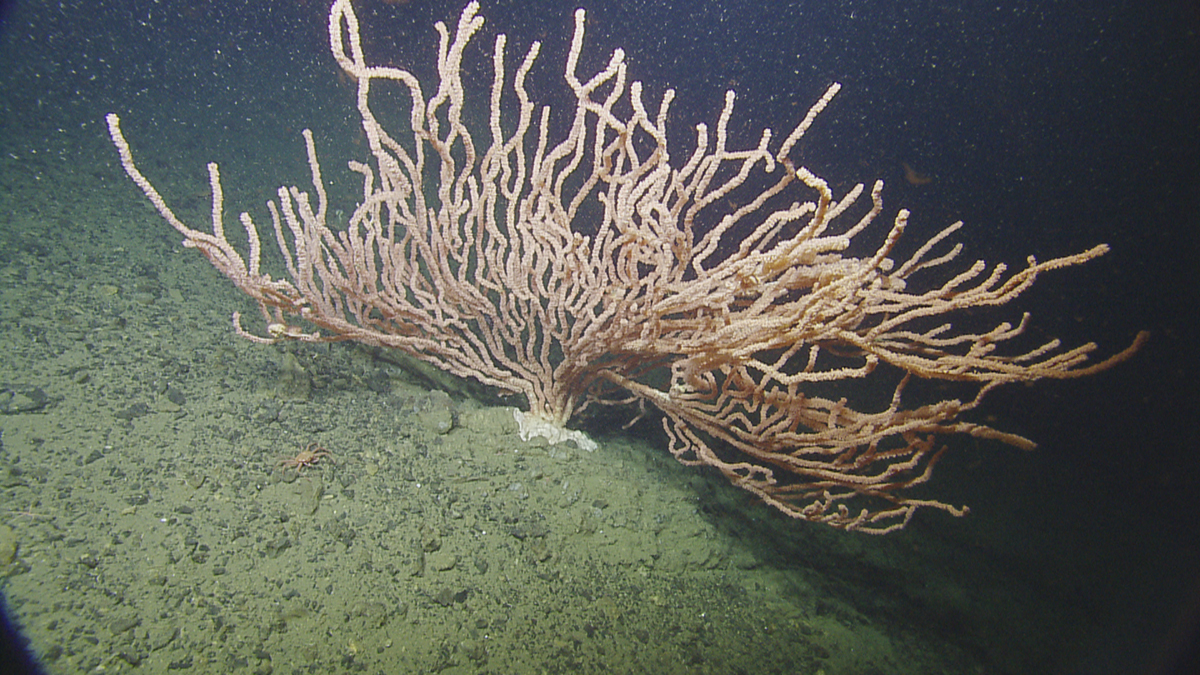

And those are just for starters. Sixty-four percent of the world’s known coral species, including the majority of those off the North American West Coast, are called octocorals, from the subclass Octocorallia. There are 3,500 species of octocoral, and they are exceptionally free-spirited when it comes to how to live. They can have soft bodies or hard bodies, they can be tall and willowy or short and branchy (or tall and branchy or short and willowy), they can have whips or fans or frills, they can live in light or dark, shallow or deep, they can start out life as free-swimming plankton or they can simply crawl out of their parents’ mouths and start not far from the family tree.

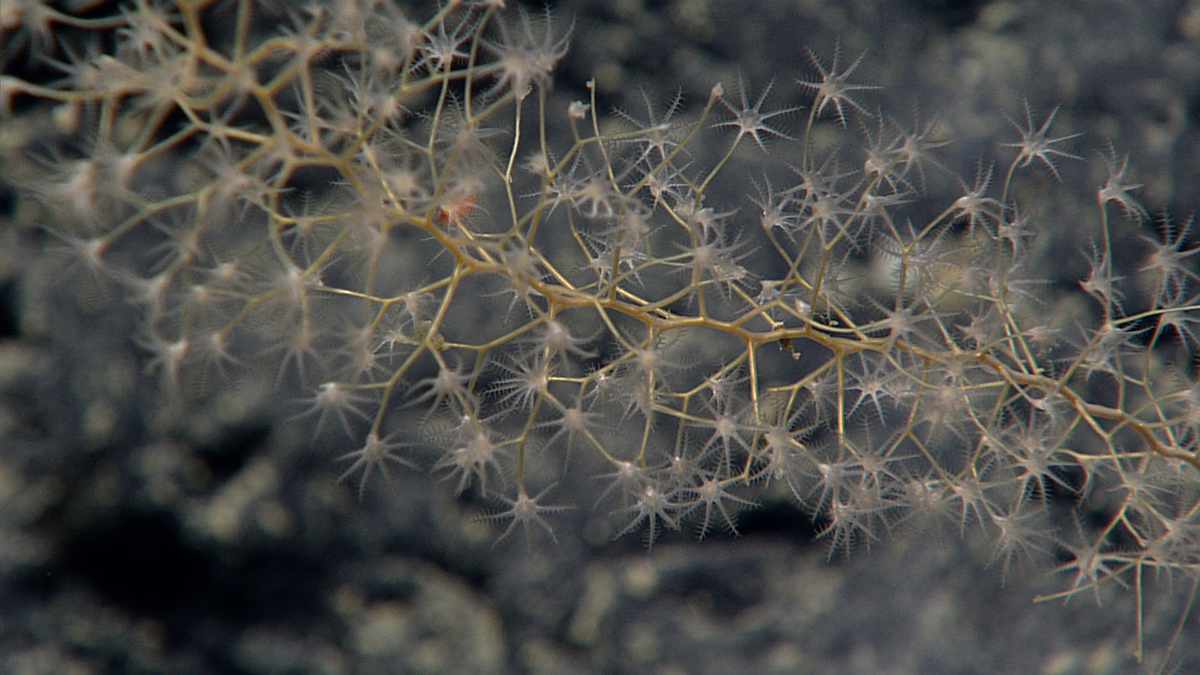

Yet one singular feature unites them. If you zoomed way in, to the level of the individual animals (called polyps) whose bodies pile by the hundreds or thousands into the intricate structures visible to humans, you would see mouths … and surrounding those mouths you would see eight feathery tentacles. The tentacles grab plankton as it drifts by in the water column, making these coral polyps not just animals but carnivores.

On a recent trip to his office Williams pulled out an octocoral specimen he’d collected from a few hundred feet of water off an area called Deep Reef, west of Half Moon Bay, in August 2018. The ROV operator had wanted to just break off a piece, but the coral was very firmly attached to the rock and so they got the whole thing, rock included. Williams, for my visit, placed it on the very center of the desk.

The coral, a species called Eugorgia rubens, is about two feet tall and intricately branched. Until they saw this one off the San Mateo County coast, it had never been seen north of Big Sur. A completely unconvincing biological pink covers the branches and stem. It looks like a wax-dipped rose-colored jewelry stand, and in its white box and tissue paper, like the kind of thing you might find for sale in a sculpture gallery. Not tropical, Williams said again, but from San Mateo County. He gently poked the branch, to show that the proteins constituting its structure were pliable, not brittle. Imagine the surprise of the scientist who first stuck an octocoral like this under a microscope and saw hundreds of feather-tentacle-ringed mouths. Dried-up, like this one, the mouths recede into the structure and become all but invisible.

“Try and convince someone that’s an animal,” Williams said.

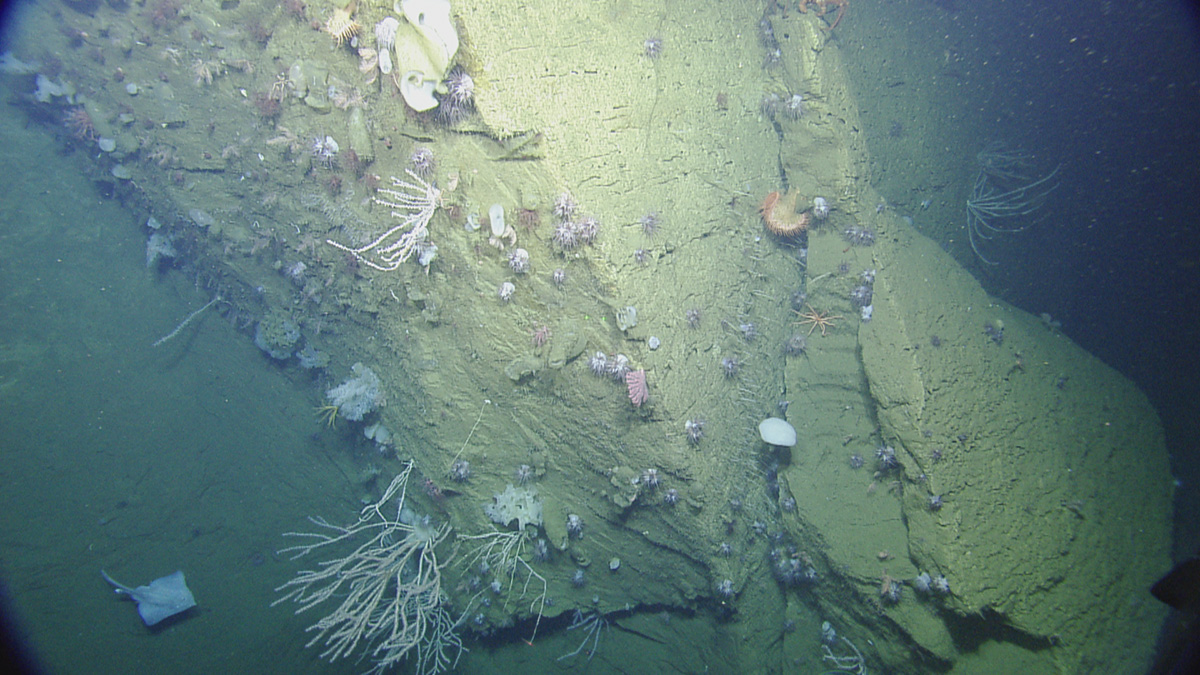

Sea floor maps of offshore California have also come into focus in the last few years, revealing vast abyssal plains, soaring rocky banks and twisting valleys that claw from the deepest reaches of the outer shelf up toward the coast. Each offers different habitat for different types of coral. At the very northern edge of the Greater Farallones sanctuary Arena Canyon, which ROVs first surveyed in 2016, drops down to more than 7,000 feet deep, with towering rock pinnacles lining the canyon walls. The pinnacles, Jan Roletto said, are covered in corals — tall, elegant bamboo corals that can live to be hundreds of years old, and branching, brightly colored bubblegum corals.

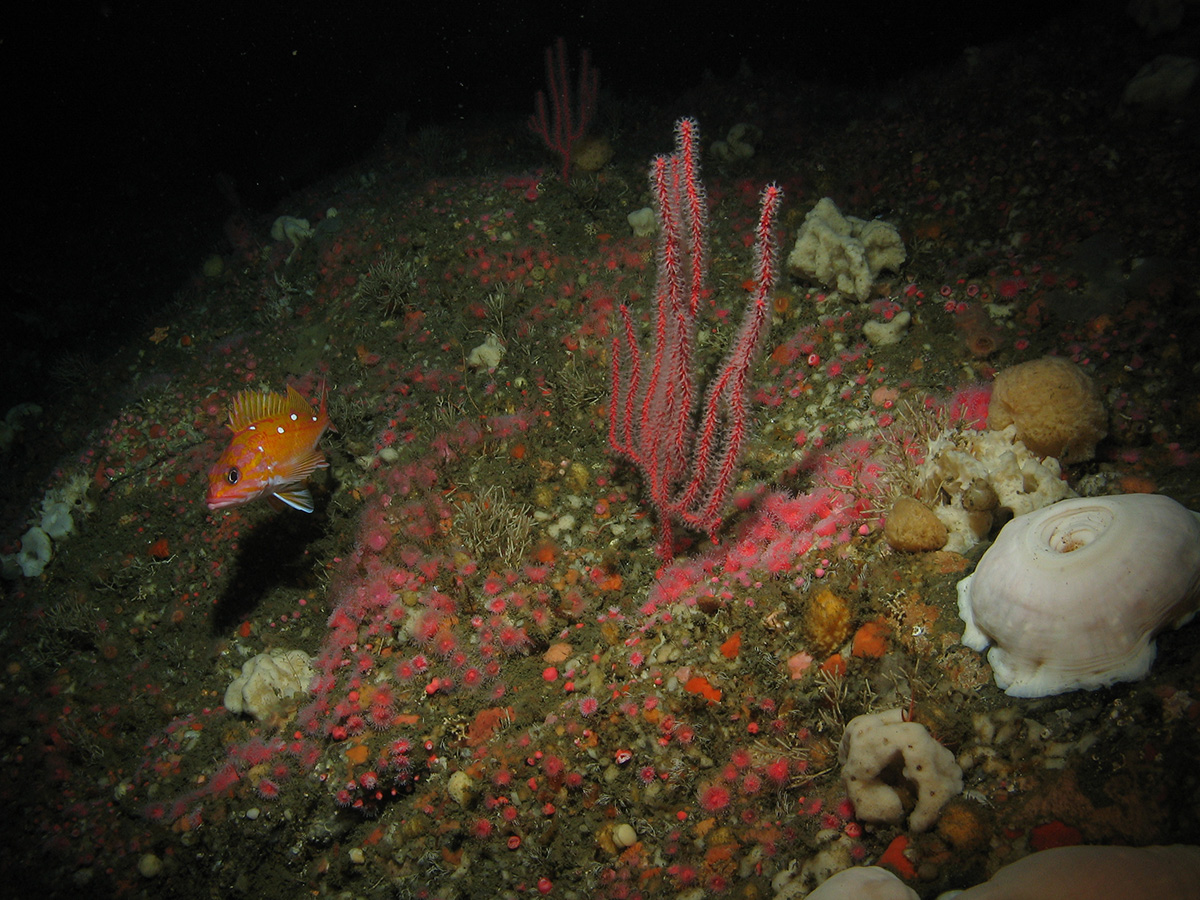

One hundred miles southeast of Arena Canyon, near the upper reaches of Cordell Bank, colorful hydrocorals in the Stylaster family shine in the fading light. Descending you might see the fern-like Parastenella ramosa, or the long zipper-like branches of a Nurella species, Graiff said. Gorgonian sea fans cling to the rock from the upper edges of the darkness down to several thousand feet, particularly the bright-red branching Chromoplexaura marki, a close relative of the new Cordell Bank species that’s common up and down the West Coast. Sea pens dot the muddy bottom, and on the scattered rocky surfaces grow more of the giant bamboo and bubblegum corals.

The ROV pilots can travel for hours and miles without seeing anything but mud and small animals, and then, Graiff said, they’ll arrive at an oasis. “It’s appearing that there are hotspots, or coral gardens if you want to say,” she said. “You’ll just hit a rockface that’s covered in large large [coral] species. Walls covered in sponges, barrel sponges and Picasso sponges.”

Graiff works as a contractor for NOAA analyzing the video of the various cruises. There can be many dozens of hours of footage from an expedition, and she watches each second of it closely. She records every species she sees with a timestamp and an estimated size, based on two lasers 10 centimeters apart that beam out from the front of the ROV. The timestamps later connect back to the ROV’s record of its own movement, allowing precise latitude and longitude coordinates for underwater rock features and species. From this, NOAA can construct a detailed inventory of what lives where in its sanctuaries.

“I enter this tranquil state every time I watch video, especially this deepwater stuff,” Graiff said. “I imagine how these geological formations formed, and how old they are, and these marine species that maybe nobody’s seen before. It’s an exploration mindset, even in zones of mud.”

Many of these recent expeditions resulted from a plan, ultimately enacted in 2015 by President Obama, to expand the boundaries of both the Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuaries. Before expanding, NOAA wanted to know what lived in the new territory, which included the depths of Bodega Canyon and Arena Canyon, and a shallower spheroid-shaped geologic feature scientists have labeled “The Football.”

Now that the expansion is done, scientists continue to learn about not just the species within the sanctuaries but the terrain itself. It’s been often said, and it’s still true, that we have better maps of the moon than we have of the deep sea, even the deep sea in the backyard of Silicon Valley. As they have for the last few years, Roletto and Cordell Bank NMS research coordinator Danielle Lipski will lead a multi-beam sonar mapping trip at the end of May to identify areas to explore, and then the Ocean Exploration Trust and E/V Nautilus will drop ROVs into the sanctuaries in October. (Streaming video from both those expeditions will be watchable from shore through the Nautilus Live’s web site.)

Roletto and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary media and public outreach specialist Mary Jane Schramm emphasized that these voyages are not just discovery for the sake of discovery, but targeting critical management areas that blend conservation with human commerce. The May trip will map seafloor off the Mendocino and Sonoma coasts that has never been mapped before to better understand what the federal government labels “essential fish habitat.” The inventories they’re compiling can inform fisheries tactics and limits, or determine where an oil spill might be most disastrous.

If all goes well this spring, Roletto said, they might even get the ROV into a canyon 30 miles west of Sea Ranch, which on her maps still doesn’t have a name. It’s never been explored before. It could — perhaps even should — have the same incomparably dramatic scenery as its neighbors.

“I believe it’s going to be just as beautiful as Arena Canyon,” Roletto said.

The 2015 sanctuary expansion added close to 3,000 square miles of ocean to the sanctuaries, most of it hardly explored. It added not just surface area but deeper water, too — entirely new habitats that are worlds different from the shallower banks. Williams has already pulled two new corals out of the depths, and there are almost certainly more to find. Presumably the same is true for an untold number of other creatures.

“A tiny tiny bit of that area is what we know,” Willams said. “And it’s poorly known. Which is amazing because California, poorly known.”

Correction: an earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the location of black corals in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. It has been updated.