Imagine watching the rise of a king tide. Now instead of the water ebbing out to the Bay as the tide turns, it stays. The high water level becomes the new normal high tide, splashing over roads and bike paths, and rising up through porous artificial fill on a twice-daily basis, and eventually threatening critical infrastructure, low-lying communities, and the ecosystems of the Bay. It’s a sobering vision of a new reality if we don’t act quickly.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Julie Beagle is the lead author of the new report San Francisco Bay Shoreline Adaptation Atlas: Working with Nature to Plan for Sea Level Rise Using Operational Landscape Units. For more information please see: adaptationatlas.sfei.org

We see precursors of this future already: highway interchanges flooding for hours at a time; the months-long shutdown of State Route 37 this past winter. Individual cities, regulatory agencies, and communities will not be able to proactively adapt to rising sea levels unless we find ways to work together, pool resources, and bring everyone along.

What about seawalls? Can’t those protect us? Such “gray” infrastructure will be a necessary part of the solution, but not the only solution in and of itself. Because water comes at us from all directions — the Bay, the ground, the hills, the sky — we need to work with our natural environment. We need to learn from nature to figure this out.

But how?

After a long day in the field several years ago, measuring and observing how far king tides traveled up streams around the Bay, several colleagues and I had an idea. We noticed how differently each stream met the Bay: some were steep where others meandered; some were lined with floodwalls and homes where others met the Bay in wide tidal marsh systems. How would sea level rise affect each of these systems and their shorelines differently? And more importantly, what could we do about it?

We began kicking around the concept of creating clear, nature-based scientific guidelines for sea level rise adaptation that worked with all the creeks and shorelines we love around San Francisco Bay. The status quo, it seemed, was that traditional shoreline protection approaches (riprap, sea walls, and other steel and concrete revetments) would continue to reign supreme. If we could provide information about natural sea level rise adaptation options (e.g., beaches, marshes, oyster reefs, eelgrass beds and others) and guidance for their application along particular shorelines, would planners, policy makers, and regulatory agencies help them they get built?

It also seemed that outlining who would need to work together might be important. Sea level rise will not stop at any boundary that we have created as humans — rather, we need to figure out a way to work together.

So we proposed a new idea: let’s adapt using nature, and with nature’s boundaries.

With funding from the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, my organization, the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), partnered with SPUR, a regional urbanist think tank, to bridge the divide between aquatic scientists, sea level rise planners, and land use planners. We gathered a team of experts, formed a technical advisory group, and convened high level representatives from most of the regional agencies who regulate the waters of the state and the Bay shoreline. These groups helped us get the science right, and also to influence how this information would be used.

In May 2019, we released our work in a report we call the “Adaptation Atlas.” And we call the framework “Operational Landscape Units for San Francisco Bay.”

Operational Landscape Units (OLUs) are connected geographic areas that we believe to be best managed as a unit. OLUs consist of physical landscape features such as rivers, floodplains, and wetlands, as well as elements of the built environment such as parking lots, landfills, and residential neighborhoods. Throughout the San Francisco Bay, we identified 30 such unique OLUs.

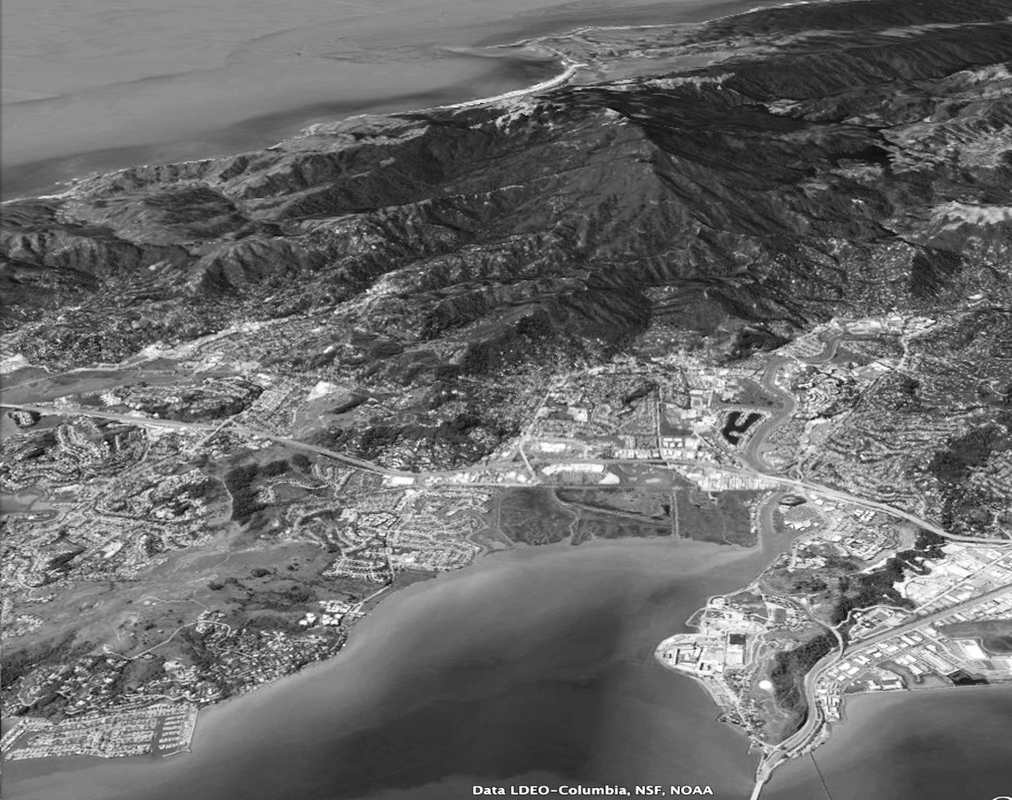

Take the Corte Madera OLU, for example. It’s characterized by the low-lying areas that drain Corte Madera Creek between Point San Pedro and Point San Quentin, two distinct promontories that stick out into the Bay to create a covelike setting. The cities of Corte Madera, Larkspur, parts of San Rafael, the Corte Madera Marsh, and several employment centers fall within this unit.

We believe the OLU perspective is needed because it connects different parts of Bayland landscapes in ways that matter. Altering the movement of sediment or water in one part of an OLU is likely to have an impact elsewhere in the OLU. So for example detaining water and sediment behind dams in a watershed would have an effect on the wetland accretion downstream; leveeing fluvial channels would reduce the width of the riparian corridor and reduce salinity gradients in the baylands; opening a diked area to tidal action could affect the sediment supply to other parcels along the same tidal channel. Because of these close connections, effective management of one feature within the OLU should require the consideration and management of the other connected features within the OLU.

OLUs cross traditional political boundaries, which often follow rivers (two counties, one watershed) or split watersheds in ways incongruous with the management of water and sediment. This is challenging though not insurmountable to overcome, and some examples exist already, like the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority, which works to manage flood protection and natural resilience in a creek that flows from the Palo Alto foothills to the Bay.

Opportunities for nature-based adaptation measures

The natural shoreline of the Bay Area has been significantly modified over time through diking, ditching, draining, dredging, development, and other changes. You can see this in the irregular large rocks that line most of the shoreline in the Central Bay, and also from the fact that standing in many of former marshlands, you can’t see the Bay because the land has subsided and is protected by vulnerable levees. Today’s shoreline needs regular maintenance to keep people safe from flooding, does not always integrate well with the Bay’s natural habitats, and is not designed to accommodate rapid sea level rise.

Our team and many others know that there are opportunities to develop nature-based adaptation strategies to modify our shorelines that will both mitigate flood risk and provide ecological benefits as sea levels rise. For instance, the restoration of a marsh, the construction of an ecotone levee, or the placement of a beach are all adaptation measures that meet this dual purpose. Individual measures may be appropriate in isolation in certain places around the Bay. In other settings, individual measures are appropriate in combination with other measures. In many cases these combinations will be hybrids, mixing nature-based measures together with conventional infrastructure measures. A tidal marsh that helps protect a flood risk management levee is one example. Many such projects are underway already, and we need many more to face the challenges ahead.

In the Adaptation Atlas, we describe over 25 adaptation measures, detailing configuration guidelines, coastal risks mitigated, ecosystem services provided, and their spatial suitability across the Bay. The result is an opportunity map for each OLU, which describes the spatial suitability of nature-based, policy, regulatory and financial adaptation measures, in what we hope will be a useful tool for adaptation planning at many scales.

How can we use OLUs?

In our proposed approach, the OLU defines the landscape setting and physical environment within which a number of appropriate measures, together with a robust vulnerability assessment, can be combined into adaptation strategies through a combination of science, engineering, and stakeholder planning.

Some local and regional governments in the Bay Area are already using OLUs as an organizing principle for vulnerability assessments and early adaptation planning. Several counties are experimenting with OLUs as a way to assess options by bring stakeholders together around a common physical area, and to begin to test potential adaptation strategies. And at the city and special district level, this information is beginning to be integrated into adaptation plans. We have a lot of ideas for how to implement these ideas. Perhaps in the long run, for example, stakeholders such as communities groups, cities, counties, flood control districts, and others could develop shared agreements or memorandums of understanding (MOUs) around adaptation planning within each OLU, as a way to formalize the planning process and assign responsibilities.

Climate adaptation action is urgently needed now, and will only become more pressing as sea level rise impacts accelerate. The intent of this research and the OLU framework is to foster and inform a collaborative, data-driven vision for resilience to sea level rise that can be implemented at multiple scales. Building on and supporting the many innovative projects already underway, this work intends to provide guidance for the regulatory community, regional governments, planners, and members of local communities on how to proactively integrate nature-based adaptation measures into adaptation plans.

It’s not straightforward work. There are big questions about equity, governance, cost, feasibility and many other uncertainties. But we have to try, and that means putting new ideas out there. As someone wise once said, the truest measure of any society, or any person, is the willingness to protect a future they will never personally experience. We all need to remember that when looking at king tides.