At the beginning of Moby Dick, right after “Call me Ishmael,” the famously-named narrator launches into a meditation on how humans are drawn—helplessly, mysteriously, inexorably—to bodies of water. “Strange!” Ishmael says. “Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land; loitering under the shady lee of yonder warehouses will not suffice. No. They must get just as nigh the water as they possibly can without falling in.”

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

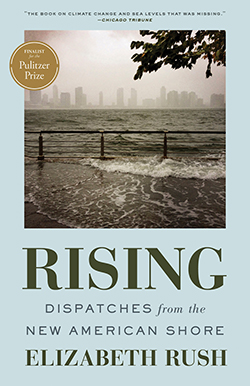

Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore

by Elizabeth Rush

328 pp, Milkweed Editions, paperback March 2019

$16.00

This pesky tendency of ours to get as nigh to water as possible—and to construct our cities and infrastructure accordingly—is what journalist Elizabeth Rush sets out to chronicle and ultimately critique in Rising, her account of sea level rise from the various sinking edges of our nation. And nowadays, not falling in is becoming more and more difficult. Climate change has walloped America’s coasts with freakishly strong storms and oceans that lap further inland, fundamentally restructuring our shorelines and the fragile wetlands that fringe them.

Rush travels to an impressive array of watery locales—she begins the book at Jacob’s Point, Rhode Island, and continues on to the Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana, where a community of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Natives wrestle with whether to stay or leave; the rotting marshes of Phippsburg, Maine; the gleaming high-rises and water-logged streets of South Florida; a Staten Island neighborhood hollowed out by Hurricane Sandy; and Pensacola, Florida, where people anxiously trade rumors about flood insurance policies. She also comes, near the end of the book, to the Bay Area, one of the country’s biggest and wealthiest metropolises, one that (she reminds us) happens to sit precariously on vast swaths of former wetland just a few feet above sea level. Looking at a historical map of the region in the Exploratorium, Rush realizes “what ought to be obvious: we shouldn’t be standing here in the first place.”

“Looking over the map, I wonder whether the Fisher Bay Observatory is designed to get visitors not just to think about sea level rise but to begin to imagine the unthinkable: unsettling the American shore.”

Rising is less about assessing the merits of various forms of sea level rise mitigation and more about bearing witness to the final destruction of our shores as we’ve known them. Near San José, Rush visits the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project, a 15,000-acre effort to restore Cargill’s old industrial salt ponds back to wetland. She comes away impressed by its ambition but skeptical of its “first-world exceptionalism and the delusion that we can design our way out of the planet-wide geophysical transformation we’ve set in motion.” “Do you ever fear that you’re playing god?” she asks the now-former executive manager of the project. The only solution truly worth considering, she argues, is to retreat, which requires a massive cultural shift (a sea change, you could say) in the way we think about developing on the coasts. “Looking over the map, I wonder whether the Fisher Bay Observatory is designed to get visitors not just to think about sea level rise but to begin to imagine the unthinkable: unsettling the American shore.”

It’s an eminently sensible suggestion. Our settlements, built up right along the sea, keep marshlands from moving to higher ground as the ocean floods them with saltwater faster than they can naturally accrete sediment. Historically unloved marsh landscapes harbor an array of wildlife, including migratory birds, and absorb storm surges—when they’re paved over, storms like Hurricane Sandy only become more deadly. And, when the land dies and begins to rot, research suggests that instead of sequestering carbon, marshes might release greenhouse gases, a terrifying feedback loop. Rush visits marshes in very different places, but the basic story is the same everywhere: As saltwater intrudes, rhizomes, the root systems that snake through marshes, retreat in search of a better freshwater/saltwater balance, while trees, whose roots aren’t so mobile, die in place. These are called rampikes, and Rush drenches them with totemic, tragic significance. In Louisiana, she encounters a statue of Jesus. “Next to the statue a dead cypress tree looms. Its empty branches mirror the man’s sacrificial gesture. It too has passed beyond the barest version of itself into death. Its roots soaked in salt.”

The trees aren’t the only ones who are trapped in place. Historically, Rush notes, swamps were refuges for runaway slaves and Native Americans who had been driven off their land. As time and industrialization progressed, wetlands became garbage dumps, then industrial areas, then low-income housing. Rush talks to members of low-income black communities in Florida who worry about policies that would force them to buy flood insurance they simply can’t afford—many homeowners, faced with storms, a lack of government investment in their neighborhood’s infrastructure, and no way to pay for all of it, have already fled. The view of their deserted former homes through Rush’s eyes is chilling.

And these economic and social inequalities will only worsen as climate change continues. Rush is especially acerbic about the Bay Area’s relative privilege, the way tech companies can blithely acquire flood-prone land to expand their campuses for employees who will likely be able to afford to protect themselves from sea level rise, unlike long-time residents. “Had the [Isle de Jean Charles] been home to Google and not to members of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe, you can bet it would be surrounded by levees today,” she writes. Which is why she advocates for organized retreat—deciding as a community, rich and poor alike, to move to higher ground together. It’s a solution that has the potential to include everyone, especially those who can’t simply put their homes on stilts or move away when things get hairy.

All true and valuable and a little hard to hear. But the most interesting parts of Rising come when we catch glimpses of people who live by the sea contending with how hard retreating actually is. “I have no uncertainty about the climate science, but I do have a lot of uncertainty about what to do,” Laura Sewall, an ecopsychologist whose home abuts a Maine coastal marsh, tells Rush. “Living here is not denial. It is a choice. …For one, I have to take into account my incredible love for sitting right here. I feel so privileged to be observing these changes so immediately. It is frightening but it is also incredibly interesting, awesome really. …I am literally watching the ocean encroaching right here in front of my house and it amazes me.” There’s a tricky, fascinating tension in settling somewhere out of love for a place (fueled, maybe, by that deep attraction to water Ishmael describes) when doing so is imprudent and possibly even part of the problem.

What’s striking, too, is seeing both the strength and fragility of communities under stress. As the Isle de Jean Charles loses people, its remaining residents face a simple but devastating network effect: the more people leave, the faster community breaks down. “Over the years the flow of people off the island has increased,” says Albert Naquin, the chief of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe. “If it continues like this, eventually there won’t be anyone left out there. And who we are, our unique Native community, will become fractured, will disappear along with the land.” While two communities in the book do ultimately decide to relocate, there are always stragglers, people who aren’t willing to give up their relationships with their environments even if it means losing their neighbors. That’s a cost of climate change, too: When we lose a particular place, we also risk losing what these places mean to us.

The book’s standout moments come when Rush’s subjects get a chance to speak for themselves, but Rush herself proves to be a distracting narrator, especially in the moments when she showily checks her privilege. In Florida she meets Alvin Turner, an elderly black man with an open wound on his leg, and feels a brief moment of fear. She then follows that admission with six consecutive sentences with the word “sorry” in them, followed further by another reminder to herself: “This man will not hurt me, I think. Alvin is not dangerous, just remote.” When she considers the plight of one of her friends on Jean Charles, “it makes me think that no matter how close we have become over the year, I will always be from away. No matter how good I get at leaving… I am not an islander, not the one who has to figure out how to say goodbye to a swollen home on a sodden island that for a good two hundred years few cared for or visited.” It’s unclear who this self-flagellating line of thought serves.

For all of Rising’s merits, I came away feeling like it was an exceedingly elegantly worded harangue, bent on exposing our hypocrisies and shot through with a subtle but off-putting undercurrent of contempt for those who disagree with its author. Rush’s argument for retreat is a sound one, but the book brooks no other alternatives. And Rising’s overbearing lyricism—its meditations on the nature of vulnerability, its doom-laden retellings of the massive harm the Hoover Dam and the atom bomb caused (parables, we understand, for the destruction technology can wreak)—takes not-so-subtle potshots at any attempt to engineer solutions to the problems sea level rise causes. But I can’t help thinking that for an issue as complex as climate change and one as deeply individual as deciding where to call home, we need all the ideas we can get.