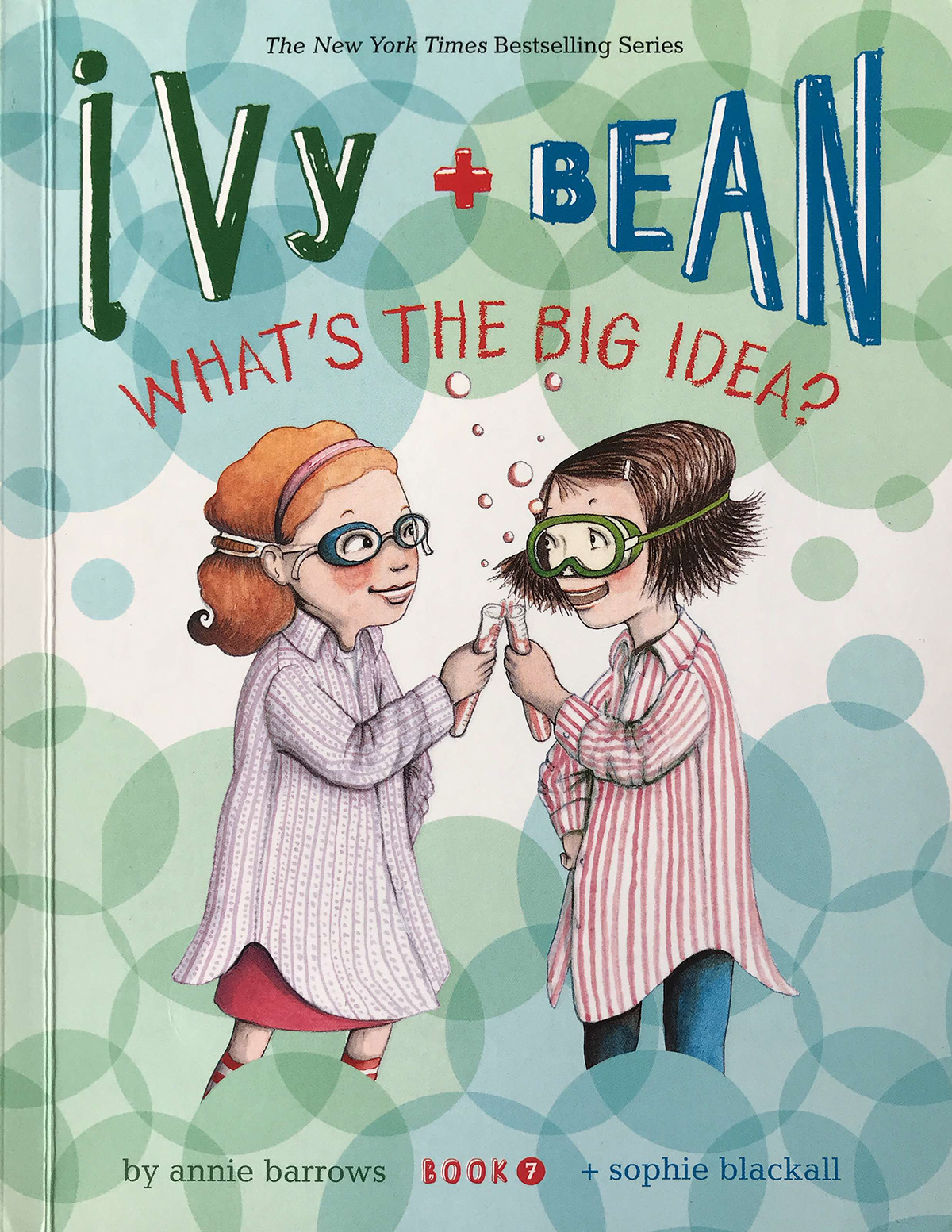

If you have elementary-school-age kids you’ve probably seen or read about the Ivy + Bean series of books. The titular heroines, the creation of East Bay writer Annie Barrows, are your classic odd-friend-pairing: studious, imaginative, clever Ivy; rambunctious, outgoing, impatient Bean. In the course of the 11-book series they navigate all the familiar stuff in the world of kids’ books — their kind-but-strict second-grade teacher, summer camp, Bean’s annoying big sister Nancy, weird old neighbors, that time they signed up for ballet class and hated it.

Then there’s book seven, Ivy + Bean: What’s the Big Idea, published in 2013. It’s another typical setup: the second-grade kids have a science fair. Ivy and Bean want to win. But here it departs from the script of the classics of children’s literature and turns into a kind of referendum on life in the Anthropocene: for the science fair the kids are going to tackle global warming.

Ivy and Bean get really stumped for a long time. The other kids come up with some hilarious solutions. (One girl, knowing people breathe out carbon dioxide, brings all her siblings in and orders them to hold their breath.) At the last minute Ivy and Bean have a brainwave. When the science fair comes along they take all the grownups outside and make them turn off their phones and just rest under the night sky. The problem, the kids decide, is that the adults have forgotten that what they love about the world and what there is to save. Here’s an excerpt from the chapter “Happy Ending”:

Ivy’s mom took Ivy’s hand. “I was happy,” she said.

“Really? You weren’t worried about poison oak and bugs?” Ivy asked.

“At first, I was, a little bit. But then I did what you said, Bean, and smelled the grass and listened to the trees. I haven’t done that in a long time.”

“And now you care about global warming?” Ivy asked.

“Sure I do.”

Ivy turned to Bean. ‘It worked!”

Bean elbowed Ivy. “Of course it worked. It couldn’t help working. It’s science.”

In the following Q&A with Barrows she talks about how she wrote the book, how she thought through the issue of global warming from a kids’ perspective, and how she arrived at the conclusion that maybe we’d all be better off if the grownups slowed down and connected more closely to nature.

Eric Simons: I’m not sure I’ve read a book quite like this where global warming is just a … plot point. It’s just part of the world.

Annie Barrows: Yes. To my mind it is pretty much like every Ivy and Bean story. This is just one of the facts of children’s lives. There’s camp, there’s the horrible ballet you have to be in, there’s global warming. These are things that happen to kids. The consciousness of global warming and the sense of it as part of the world seemed to me in the same way as for instance ballet does, to lend itself to a story. It was, however, a particularly hard story to write.

ES: So where did you start?

AB: Well, to go way back in the beginning of Ivy and Bean, I wrote the first book on a whim because my seven-year-old ran out of stuff to read. The second book sort of came out of there being a haunted janitor’s closet at my daughter’s school.

When later, I began casting about for topics, I was interested in science fairs, science projects, science and little kids, and what they think of it, the whole scientific method as it relates to how kids think about things. Then my younger daughter when she was seven came home one day, and basically took me aside and whispered the horrible news that there was global warming and the animals were dying. And she said, “you know, we all have to do something about this. I’m going to go dig up the lawn.”

So, we talked about that for a while. About how that seemed like kind of an OK idea, but maybe there was another way. She said her friend Jared was waking up every day and banging his head into the wall, to even out the chances for the animals. I immediately should have called his mother, but I thought it was so funny I didn’t. That’s how I started thinking about this global warming as a story idea. Then I started writing it, and I really got stuck.

ES: What happened?

AB: My contention is you don’t write a book for little kids that ends with them all realizing they are powerless. That to me is a sin. The whole point of the Ivy and Bean books is that I want kids to feel that their understanding of the world is a legitimate understanding and is borne out by reality. They might be wrong about facts, but they’re never wrong in what they want. Never not once ever. To take global warming as a process, and to take this principle of mine, that was a really hard mix.

The whole point of the Ivy and Bean books is that I want kids to feel that their understanding of the world is a legitimate understanding and is borne out by reality. They might be wrong about facts, but they’re never wrong in what they want.

So, I did what I always do, which is sit under my desk with my feet up in the air for a long time thinking, what would happen? What can they do? And then this peaceful idea came: that really the problem is how alienated the grownups are–not the kids—but how alienated grownups are from the natural world. How they view it with fear, and the way they respond, “Ahhh, it’s a bug, ohmygod, oh no! Don’t leave the windows open, ahhhh don’t leave the door open, oh don’t go outside, it’s too hot! You’ve got to wear sunscreen, you’ve got to wear a hat!” I thought, that’s the weird thing. So, then I had a way out. But it really took a long time to get there.

ES: Some of the climate solutions the kids come up with are pretty great though. The kids having their siblings hold their breath. Was that based on real-life?

AB: No, I made that one up. Then I thought, I’m so opposed to books being educational, but then I did feel I should write some stuff about what they had tried and talk about it a little bit. I’ve been complimented for my gentle ability to understand where kids are at in terms of science comprehension, but that’s exactly where I’m at too. I don’t know anything.

ES: You talked about how kids have to have agency. You’ve written adult books too. How’s it different getting into the voice and writing about something that can be a downer and is also just complicated? Did you have to approach that a certain way?

AB: Scrape away the adult, scrape away the adult. That is the task of the children’s book writer. Just take it away. Excavate, excavate. Eventually, you find it. It’s there, you were once this person. But it’s a question I’m often, often asked, because I write both: which one is easier. What’s expected is I’ll say “oh it’s so easy writing for children: they’re all so cute.” And the truth is that for children the thinking is so much harder. It’s about getting to what a kid really would think. It’s really hard. The writing is not so hard because it’s contained. You’ve got 8,500 words, so you’ve got to be pretty clear about what you’re doing before you start. But I approach all of it by trying so, so hard to remember what I wanted.

ES: The kids’ characterization of grownups here — their concept of what grownups think about —

AB: Right. It’s sort of pity.

ES: It’s really captured in there! And then leaving them outside to just relax.

AB: “You know, dad, you couldn’t think of a good idea because you’re a grownup. It’s OK, you poor old lump.” I don’t think most kids can express that, or have parents who are receptive to that. But I do think kids sometimes think, “grownups are so boring.” I don’t know why you don’t overhear kids saying, “what the hell is the matter with them, they’re talking about real estate! Why? Don’t they have anything better to do? They never have any fun!”

ES: I’m curious, did you get feedback about this? I assume you get a lot of reader comments because kids.

AB: Yes. I get a lot of reader comments.

ES: You must always get comments. Were they different this time around?

AB: I get more comments from grownups about this book. There’s a couple of things. There’s the whole wingnut element; if you look at Amazon you can see it, “she’s a liberal poisoning our children’s minds with this false blah blah.” But then I’ve got some lovely, lovely emails from scientists saying, “I couldn’t believe you’d addressed this topic; I didn’t know this book was about climate change until I got halfway through it, and then I cried.” It’s been really nice to hear from that community that it has meant something to them. I hear from kids all the time, but they don’t view this one as that different. This doesn’t mean anything that different to them than the ghost in the bathroom.

ES: That’s one of the things that interested me the most. You’re not a climate writer.

AB: Like I say, this is about my level right here.

I wrote a big long essay like a stupid grownup. And I thought, would I ever read this in a million years? No, I would not.

ES: So you wrote this part at the end where you sort of talked about the actual science of why things like throwing ice cubes in the air (Bean has the idea that they can cool the air down by emptying their freezer into it) won’t work. I’m curious about the voice for writing Climate Science 101 for 8-year-olds. How did you do it?

AB: I wrote a big long thing and then I hated myself. I wrote a big long essay like a stupid grownup. And I thought, would I ever read this in a million years? No, I would not. Again, scrape, scrape, scrape away the adult. I asked myself, Is there good news? What can I tell them that they might want to know? Just write enough to contextualize the book. That’s all. When I first read the manuscript to my younger daughter, the ice cube thing made perfect sense to her. Nancy [Bean’s big sister, who ridicules the ice cube idea] was just a big meanie and was probably lying anyway because that’s what Nancy does. She’s a wet blanket. So then I had to explain to [my daughter], “No, sorry, Nancy’s right about this one.” I was remembering that when I wrote the science note the second time.

ES: Has living in the Bay Area affected the way you write these books? Are there parks or any specific places you think about when you’re writing?

AB: I try not to be too specific. I want it to be broad enough so people can relate to it all over the place. But I think the way I write is informed by where I grew up, which is here, and by the fact I grew up in a time when you just went outside, because that’s what people did. One of the things that is important to me, that is actually an active motivating force in the creation of these stories is that I want to show kids outside. I want them to go as far as they possibly can, have as much freedom of movement as they can, in the outdoors. And to view it as a benign space. And to feel that they’re no safer inside than they are outside.

ES: I’m curious if after reading the conclusion of your own book you thought, “I should go outside more.”

AB: I feel like everybody should be outside all the time. Maybe I’m more motivated to go help pick up trash and stuff. But you know, the next book I wrote was about money and cheese.