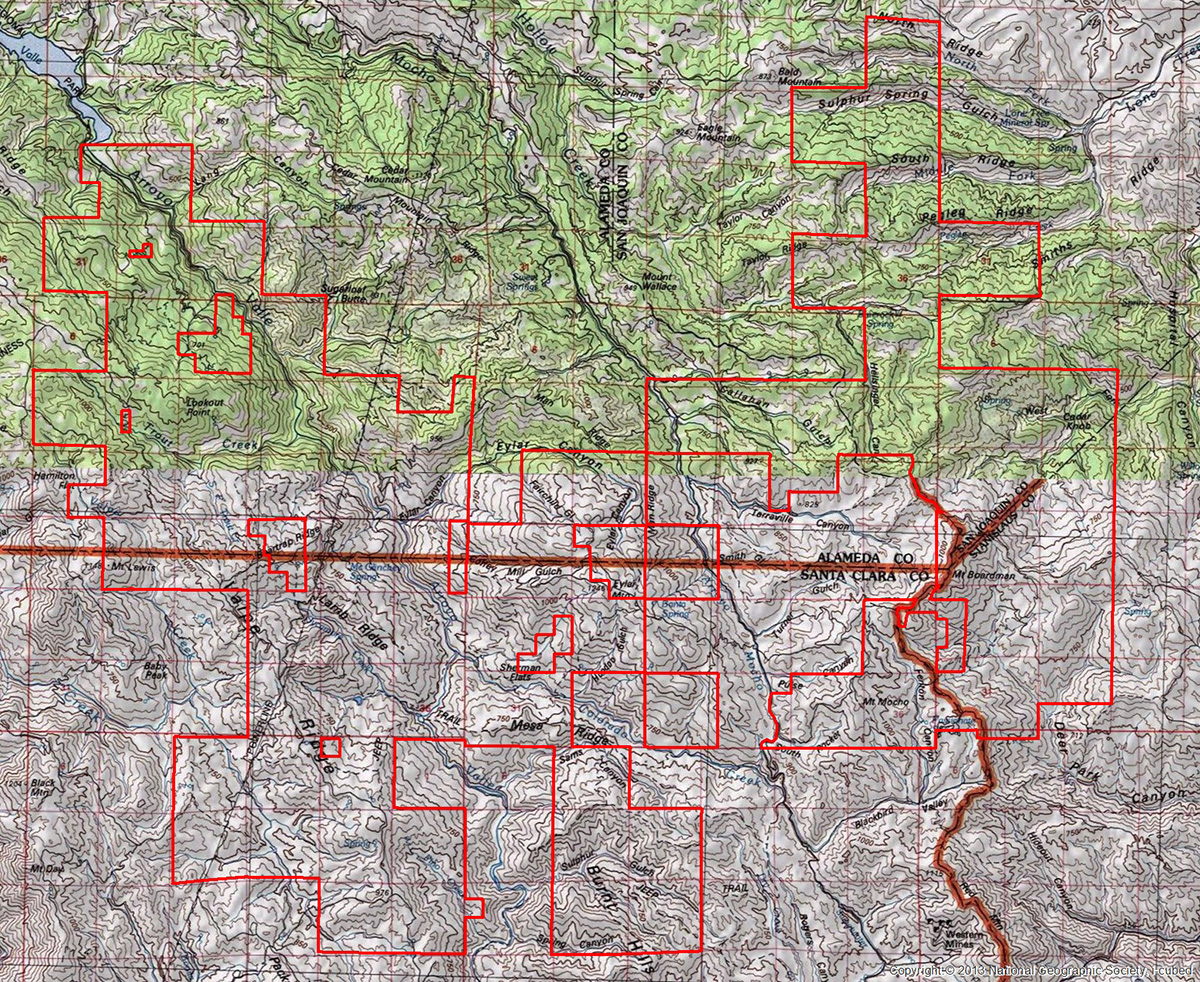

You get almost as much a sense of the ecological value of the N3 Ranch property, 50,000 East Bay acres listed for sale for $72 million in early July, from looking at a map as you do from the spectacular drone footage the owners released with the listing.

In a regional conservation era defined by linkages and corridors, N3 connects huge swaths of protected lands. The largest property currently for sale in the state, it runs east-west from Corral Hollow near Tracy to the East Bay Regional Park District’s Del Valle reservoir. It runs north-south past the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission’s Calaveras and San Antonio reservoirs, and the EBRPD’s Sunol and Ohlone Regional Wilderness. It wraps up past the east side of Mission Peak. It nearly connects the unique habitats of Mount Diablo State Park to the unique habitats of Henry Coe State Park. It fills in a major chunk of a greenbelt stretching from the Delta to Gilroy.

“Less water, less fragmentation, fewer paved roads, more biodiversity,” said Save Mount Diablo Land Conservation Director Seth Adams. “I don’t even have to go onto this property to know it’s rough, rugged, incredibly diverse, and huge.”

Adams kept returning to the size of the property. It’s more than twice as big as Mount Diablo State Park. It’s bigger than the city of San Francisco. It’s the nexus of four different counties, with 20,000 acres in Santa Clara, 8,000 acres in Alameda, 7,000 acres in Stanislaus, and 5,000 acres in San Joaquin.

It would be a botanical wonderland back there, says Nomad Ecology botanist Heath Bartosh, who has spent decades surveying plant habitats in the East Bay. “Undoubtedly,” Bartosh said, “there are things that are undescribed, or bolstering other populations [of rare plants].”

Bartosh talked animatedly of the discoveries the first botanist to thoroughly survey the N3 property might make if a conservation-minded owner can acquire the property. He anticipates new species, new county records, and new records of plants known previously only from the Sierra Nevada. Because N3, like Mount Diablo or Henry Coe, sits at the confluence of the inner coast range and valley and foothill habitats, it would likely have numerous mixing zones with uniquely evolved local populations.

It also hasn’t been thoroughly surveyed by a serious scientist since botanical legend Helen Sharsmith visited between 1934-1937. Sharsmith found 761 species of vascular plants in the region and wrote a journal article based on her travels called “Flora of the Mount Hamilton Range of California.” Modern botanists say there are roughly 3,000 species of vascular plants in the California Floristic Province, meaning that something like 25 percent of California’s internationally renowned plant life might be found in just this relatively small area around Mount Hamilton.

Sharsmith noted in her introduction that the only botanist who’d thoroughly surveyed the area before her was William Brewer in 1862, and that the result of his expedition was the type specimens of three plants named after himself. (Brewer’s jewelflower, Streptanthus Breweri, Brewer’s monardella, Monardella breweri, and Brewer’s clarkia, Clarkia breweri.) Brewer also collected the type specimen for the desert lantern (Oenothera deltoides ssp. cognata). Sharsmith also wrote that while the western edges of the Hamilton Range had largely been overrun by invasive pasture grasses and weeds, many of the eastern edges remained, at that time, minimally affected.

The N3 property includes at least two peaks taller than Mount Diablo. It has numerous creeks and seasonal arroyos, some of which make up the upper watershed for the SFPUC’s two reservoirs. It has rolling oak woodlands, bay-laurel forests, and open meadows. It holds serpentine grasslands, which tend to harbor some of California’s rarest endemic plants.

The ranch has been owned by the same family since Sharsmith surveyed it, and has been both a working cattle ranch and private hunting ground, with 14 hunting cabins for hunters to pursue tule elk and black-tailed deer.

Rancher Clara Vickers purchased the first pieces of N3 in the 1930s and 1940s. Born on an Arizona cattle ranch in the late 1880s, Vickers moved with her father — a land, cattle, and oil speculator — to California after a drought affected the family’s ranches in Arizona. In the early 1900s the family bought Santa Rosa Island, the second-largest of the Channel Islands. (The family sold Santa Rosa to the National Parks Service for $30 million in 1986.) Vickers turned her attention to N3 in the 1930s. Her son, Roy Edgar “Ted” Naftzger, Jr. — a Stanford grad, sport fisherman, and coin collector — expanded the ranch through the 1950s and 1960s. Naftzger, Jr. died in 2007. His daughters, who live in Los Angeles, decided to sell after their mother died in 2015.

“It’s a big property, not just acreage wise, there’s big mountains, canyons, meadows,” said Todd Renfrew, the listing agent at California Outdoor Properties. “The land itself looks like it did 2,000 years ago.”

Before the Vickers-Naftzger family arrived, N3 fell on the eastern edge of Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone territory. When the Mexican government secularized the California missions in the 1830s, hundreds or perhaps thousands of Ohlone returned to the greater Livermore and Pleasanton area, and established a large community in Pleasanton as well as smaller communities around Arroyo del Mocho — parts of which are now on the N3 property — and in parts of what are now the East Bay Regional Park District and SFPUC watershed land. A partial Census in 1900 shows 20 Ohlone living in Murray Township, the site in Alameda County of the future N3 ranch.

Between 1851-1852 the remaining Bay Area Ohlone signed treaties with government representatives that granted them access to 8.5 million acres of land in central California to cede 64 million acres to the United States. But the Senate never ratified any of the treaties — and in the late 1920s, just before the Naftzger family turned to Northern California in search of new ranchland, the Bay Area Ohlone, until then recognized as a sovereign tribe called the Verona Band of Alameda County by the U.S. government, were stripped of their tribal status. Without formal organizational power, the communities in Pleasanton and Livermore drifted apart as individual families sought work elsewhere in the Bay Area. Many joined the Army to fight in World War I and II. The 500 enrolled members of the Muwekma Ohlone today have no tribal land and as of 2019 have had their petition to regain federal recognition rejected by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“On this ranch, there are probably a multitude of ancestral heritage sites that of course the tribe will never have access to,” says San Jose State emeritus anthropology lecturer Alan Leventhal, who has worked with the Muwekma Ohlone for nearly 40 years. “That’s the politics of erasure which the tribe has faced since 1927. If you don’t mention their contributions or their history or their heritage, they’re not considered stakeholders.”

N3 likely won’t be developed, everyone agrees. The terrain is too steep, there’s no water, and the owners and realtor say they don’t want to sell to a developer. The ranch is enrolled in the Williamson Act, meaning it receives tax breaks for keeping it agricultural. But the owners and realtor do say they want to sell it as a single property, not in pieces. They’re willing to wait, Renfrew said, for the right offer. Land sales can take months if not years.

Conservation agencies large and small have expressed interest. Mostly off the record, they describe N3 as both a critical conservation purchase and a tough price tag. At $72 million, it’s a steep initial cost. But that’s just for starters: maintenance of the land would be difficult. It’s a rugged property with hundreds of miles of fire roads and fences to clean up and maintain. It would have to be surveyed, and stewarded, even though most parts of it are inaccessible.

So they’ve all taken a look, and are balancing the value of the land with the value of money.

“A chance to protect a critical juncture area at this scale doesn’t happen very often,” Save Mount Diablo’s Adams said. “Diablo Range conservation is the next big California conservation story. This is the critical piece.”

It’s possible too that the ranch simply stays private. It makes an ideal trophy purchase for someone with $70 million to spend attaching their name to a ranch. Renfrew, the listing agent, said he’s received a number of calls about the ranch as an investment property. Just park your money in East Bay land and let it sit.

Whether it’s a consortium of land trusts, or a new private owner, or something unforeseen, it’ll likely be a while.

“Large ranches, they take time to sell,” Renfrew said. “It’s usually a year or two.”

Correction: A previous version of this story had the incorrect title for Seth Adams. He is the land conservation director at Save Mount Diablo.