California’s 2013-2016 drought has been blamed for the death of 147 million trees in the Sierra Nevada. Three years of far-below-average rainfall changed ecosystems, drained groundwater, and left the state desiccated and primed for major wildfires.

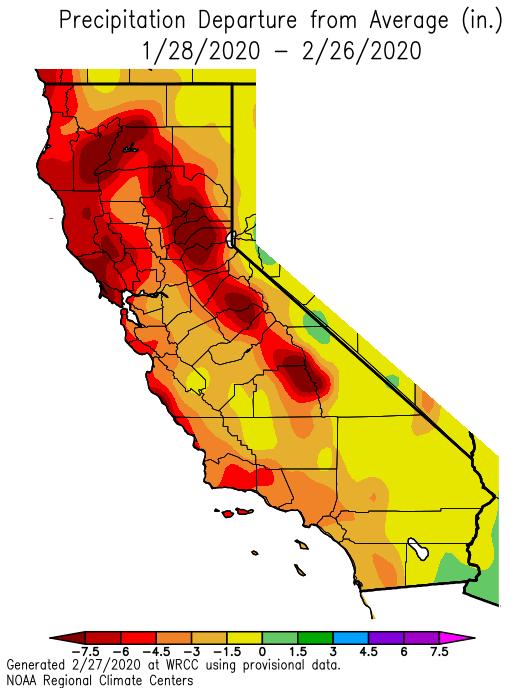

It was an extreme drought, and it might not have ended yet. A dry February 2020, in which San Francisco will not record any rain for the first time since 1864, raises the possibility that perhaps the last two rainy winters were just brief interruptions in a dry spell that might have to more properly be measured in decades, not years.

“From the paleoclimate perspective, megadrought was common,” said Shelley Crausbay, a senior scientist at Conservation Science Partners. “We may be in a megadrought now in California. But it’s too much of a new paradigm to say that out loud.”

The state’s reservoirs are full and for now at least there are no restrictions on human water use beyond agriculture. But whether people have access to water is only one way to define a drought. There’s a world beyond our cities and farms, in other words, and two winter months without rain can be hard on it, let alone six or seven exceptionally dry years in a decade. In a 2017 article for the American Meteorological Society, Crausbay and other scientists laid out a definition of what they called “ecological drought”, a lack of rain or snow that pushes natural ecosystems past a point of vulnerability, leading to events like mass tree die-offs or widespread wildfire.

On that scale, it’s harder to say that the previous drought stopped when the rain returned. Even by the end of 2016, when nearby reservoirs had filled up again after several years of dry weather, scientists at the US Geological Survey estimated it would take three more years of normal rain to restore the watershed in the Russian River basin.

Which brings up a bigger point, Crausbay said: we didn’t always need a definition of ecological drought. California’s ecosystems evolved with occasional dry spells, and mostly withstood them. What mattered about a “drought” could be measured by whether farms had enough water. Like the now-widespread use of the word “Anthropocene” to describe a human-dominated geological era, the concept of ecological drought shows the ways our changed world demands new language.

“Our drought conditions are changing,” Crausbay said. “Our droughts are hotter, primarily, and they’re stronger, and longer, and they cover a bigger spatial extent. In previous decades, we weren’t in a world where drought was so extreme. We weren’t used to seeing these kinds of impacts. It wasn’t on the table, it wasn’t part of our reality. But that reality is changing now.”

The basic problem is that it is warmer. In the past we had cold droughts and warm droughts and medium-temperature droughts, said Daniel Swain, a research fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado and UCLA climate scientist. Now, because of climate change, we mostly just have warm droughts. Some scientists concluded that the combination of warmth and lack of rain between 2012-2015 was the most severe California had seen in more than a thousand years. Swain said that climate change fingerprints are so obvious in most modern extreme heat waves that looking for them “is like shooting fish in a barrel.”

And heat makes everything about a drought worse. Average mean temperatures in California have warmed by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1890s, with nighttime minimum temperatures rising even faster. That means less snow, more evaporation, drier soil, and plants and animals needing more water at a time when it’s least available.

“On some level, whatever drought used to mean means something new now in a warming world,” Swain said. “It’s better to have a drought when the reservoirs are not low than when they are. But it doesn’t mean we’re not in a drought when we don’t have critically low reservoir levels. The trees don’t benefit from those reservoirs. If we care about things like wildfire or ecosystem health, then the status of the reservoirs is completely irrelevant.”

How to use water in a dry year is often cast as a battle of people versus fish. Scientists call for water to flow through the rivers to benefit salmon and smelt, while farmers call for that water to be diverted to feed the world. Crausbay said there’s something missing from that dichotomy, though, and that anyone who’s seen a fire tearing through bone-dry wildlands knows ecological drought can be measured in human cost.

“Natural ecosystems are more than just a pretty postage stamp for us to look at,” she said. “If we’re planning water allocation and not thinking about ecosystems, it’s going to come back and bite us.”

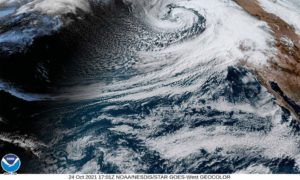

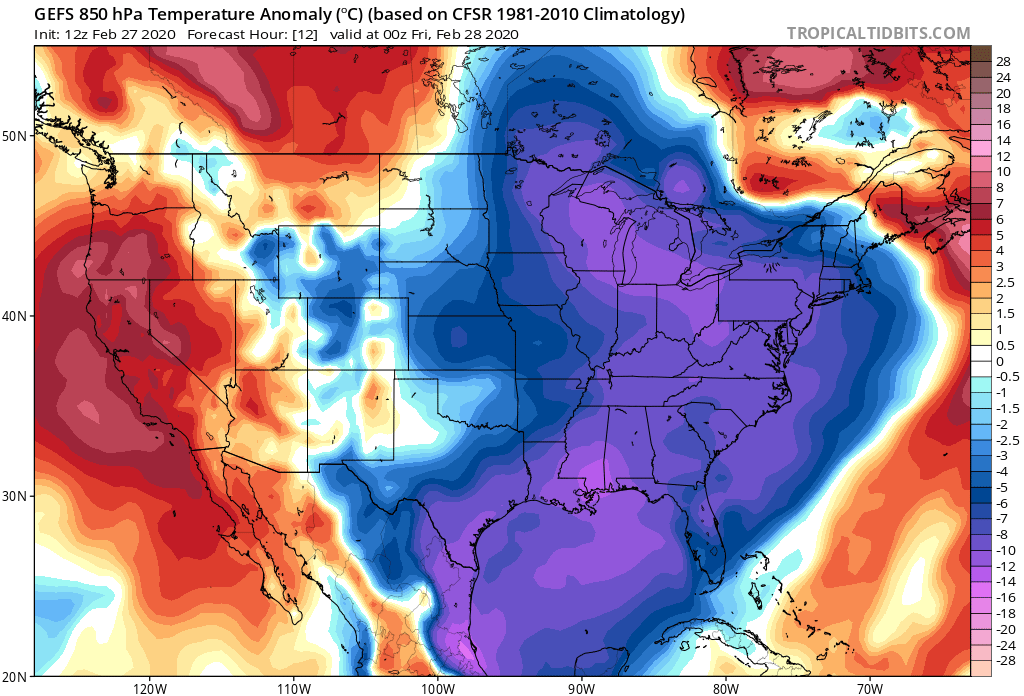

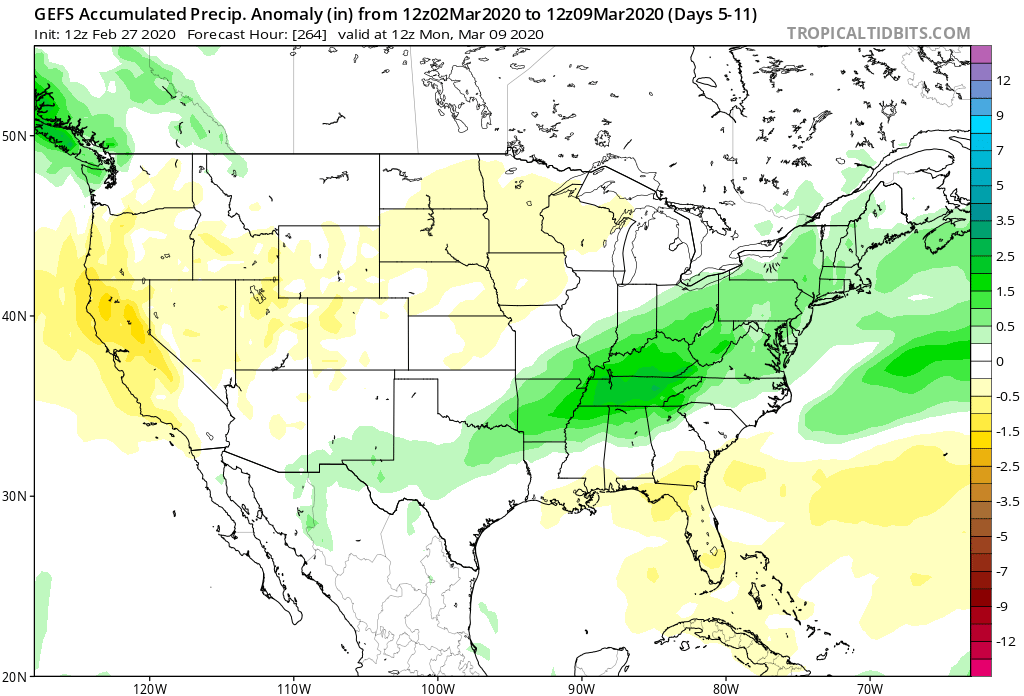

On a very basic level, this year’s lack of rain has been caused by a strong high-pressure ridge just off the North American West Coast. It’s similar to the pattern that caused the 2013-2015 drought. What’s different this year is that the warm dry pattern essentially has spread across the world. The 2013 California drought was characterized by what scientists called a “dipole,” a very warm west and a very cold eastern United States. This year the eastern United States has been warm, and so has Scandinavia, with ski-loving countries like Norway wondering where all the snow has gone.

So what’s causing this year’s pattern? It’s still too early to say.

Scientists connected patterns of sea surface temperatures in the western tropical Pacific Ocean — the area around Indonesia — to the rise and persistence of the North Pacific ridge in 2013-2015. There are similarities between how that area of the tropical ocean looked then and how it looked to start 2020, although University of Washington atmospheric scientist Dennis Hartmann, who wrote a 2015 paper establishing the link between the tropical ocean and California rain, said he hasn’t looked closely this year.

Going one step farther, in a 2017 article in the journal Nature Communications, Ivana Cvijanovic and colleagues at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory suggested that diminishing Arctic sea ice primes the tropical Pacific to enter the pattern that leads to the blocking ridge over California. After a freakishly warm Arctic fall, 2020 started with record-low sea ice. While a cold January and February pushed the ice area above its average over the last decade, it’s still hundreds of thousands of square miles below the averages for earlier decades.

Cvijanovic, now a research scientist at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center in Spain, said there’s a well-known link in paleoclimate research between temperature in the high latitudes and rainfall in the tropics. So using climate models, Cvijanovic looked ahead at how temperature changes and the loss of sea ice in the Arctic might be linked to rain in the tropics and so to mid-latitude places like California. The loss of sea ice predicted over the coming decades, the paper concluded, “could substantially impact California’s precipitation.”

Could this year’s Arctic be contributing to this year’s dry California? It’s too hard to link one single ice year with one single drought year, Cvijanovic said. But, she said, it’s “not inconsistent with what we saw.”

Intriguingly, Swain said, seasonal forecasts from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center last fall predicted a dry winter. Seasonal forecasts are inconsistent, and Swain said that of course you can’t celebrate a successful prediction based on a sample size of one. But the models were definite and consistent in calling for a dry winter, so something in the conditions of the world in September 2019 was a clue. Perhaps it was the sea ice, or the western tropical Pacific, or something about land soil moisture, or anomalous warmth in the Indian Ocean, Swain said. Whatever it was, it would be nice to know what those models saw.

“The seasonal forecasts are often maligned,” Swain said. “They don’t have a great track record. But this year they were really emphatic in predicting a dry winter for California. They ended up being very right.”