The Palomarin Field Station of Point Blue Conservation Science, a small outpost of human infrastructure at the southern boundary of Point Reyes National Seashore, has been a home base for bird studies spanning more than 50 years. Generations of researchers have worked there, producing hundreds of volumes of data, which include many still not-digitized hand-written notes, observations, and sketches.

On August 18, eight miles away from Palomarin in remote and rugged terrain north of Bear Valley, a wildfire ignited by lightning started to gobble up tracts of coastal chaparral and stands of bone-dry Douglas fir. Named for the nearest park trail, the Woodward fire erupted in size, from some 50 acres that afternoon to 1,000 acres overnight to more than 2,500 acres in the following days. By late Tuesday, as dense clouds of smoke rose above Inverness Ridge and cascaded toward the field station and town of Bolinas, a rescue operation began.

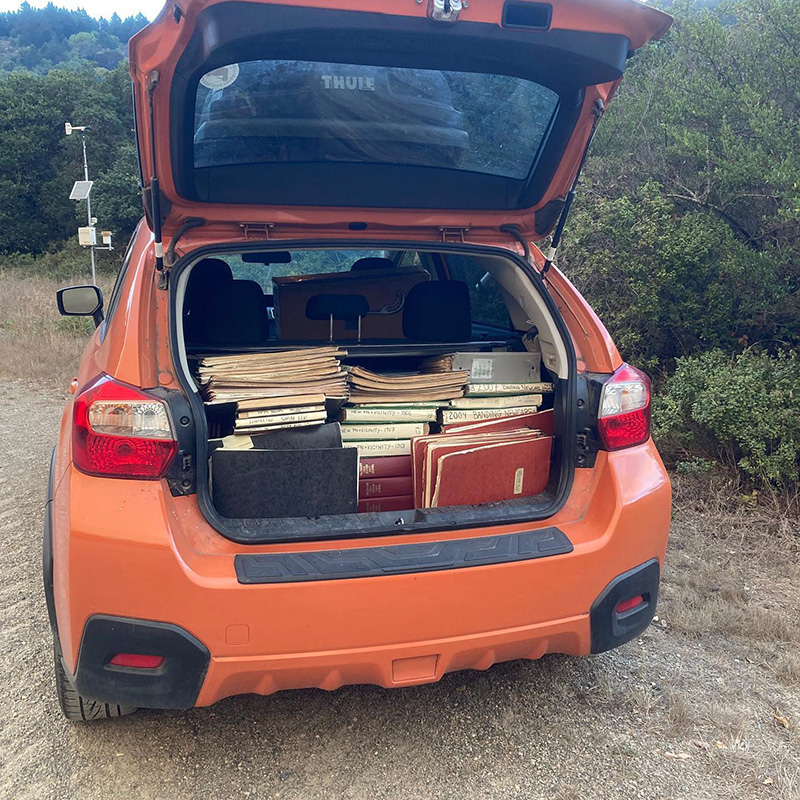

With acrid smoke and ash in the air, and continuing dry winds from the north, personnel at the field station set in motion a protocol they had established for just such an emergency. Three staff biologists and five seasonal interns worked there together on Tuesday evening and again on Wednesday morning. From the library and data room, where masses of bird and ecological data are stored, they pulled the volumes marked top-priority, then carefully stacked the dozens of notebooks, data binders, and bound journals into the cargo areas of their cars.

The scientists were acting to protect information that currently is irreplaceable. In essence, this was an operation to rescue knowledge.

The field journals and binders they carried away belong to a vast trove of records spanning more than five decades. Says ecologist Diana Humple, Point Blue’s program lead at the Palomarin Field Station, “Unlike many of the primary records stored at Palo, these particular books hold data that haven’t yet been fully digitized. Their contents include bird behavior observations, sketches, and hand-written notes.”

There are thousands of daily journal pages chronicling Point Blue’s field work on three nesting-bird study plots near the field station and at bird-banding sites throughout West Marin, along with the personal narratives of Palomarin interns, staff, and volunteers. Other binders in the collection represent millions of individual pieces of data—from weather subtleties, to vegetation (how tall the Douglas firs have grown, when the blackberry plants start fruiting), to details pertaining to all the birds nesting in an area, as well as to migrating birds.

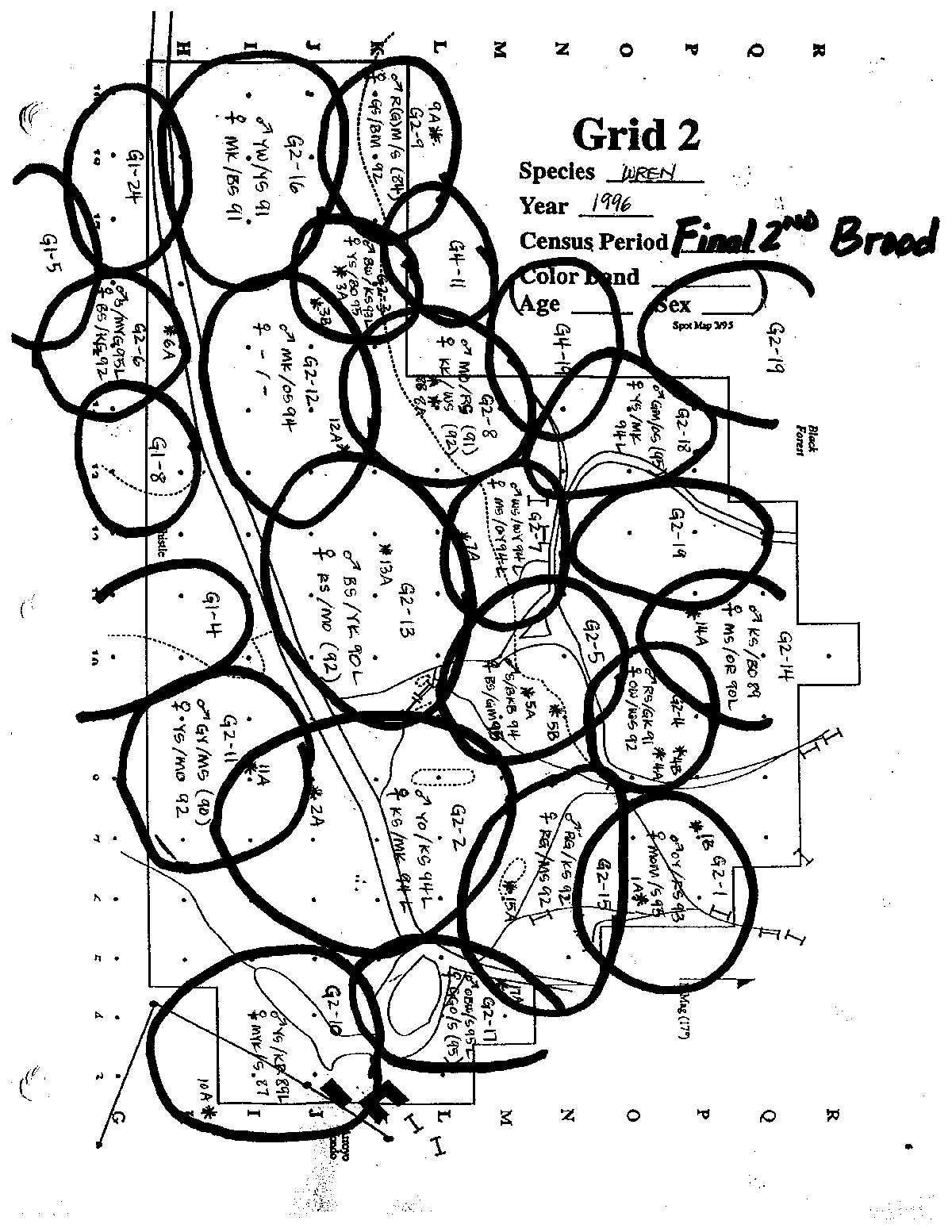

An intern biologist responsible for a given nest plot spends hours every day in spring and summer, observing and charting birds’ activities. Among the common nesting bird species here are wrentit, song sparrow, Nuttall’s white-crowned sparrow, spotted towhee, Swainson’s Thrush and Wilson’s warbler. One way that nest searchers record these birds’ intimate relationships with their habitat is a hand-drawn map of each territory: how large or small it is; how it may intersect or overlap with the neighboring birds’; if it expands or shrinks during a given season; where the bird places its nest(s); how a territory changes over time; who mates with whom (many resident birds can be identified individually by the colored bands researchers have placed on their legs); and even how a sedentary species like the wrentit may share its territory with its own kin from one year to the next.

As you might guess, the only way to capture such fine-grained knowledge is a medium that harkens back through times past—ink on paper.

“Each of these hand-written, hand-drawn records tells a small story about individual birds, a specific year, a given breeding site, a parcel of land, the habitat,” Humple says. “Then, collectively, these data allow us to tell a larger and longer story—across a half-century—about how well the entire bird community is doing, about the habitat and weather as they change over time, and about this region and what to expect going forward.

“That’s why we prioritized the particular data binders we evacuated. Many of our records at Palo, like the rest of Point Blue’s data, now have been digitized—entered, scanned, or both. We have been working backwards through time and digitizing all the rest, but this is a massive undertaking. Eventually, we hope to have the resources needed to digitize all our information. But that hasn’t been possible yet; so, many of our data binders are uniquely vulnerable to being lost in a fire.”

The value of all this fine-grained knowledge is amplified by the extraordinary duration and constancy of the research effort. Long-term continuity is exceptional in ecological monitoring, because the field work is labor-intensive and challenging to sustain across the years. Point Blue (founded as Point Reyes Bird Observatory) began work at Palomarin in 1966. An original focus, which continues today, is mist-net monitoring to document occurrence and trends among migratory songbirds. By now, the landbird studies at Palomarin have yielded one of Point Blue’s four keystone data sets, from which scientists can tease out signals of environmental change, for example, earlier arrivals of migratory songbirds in spring.

The constancy of this data-gathering effort depends on the dedication of intern field biologists—who compete for a niche at Point Blue. The intern training program is widely renowned and, over the years, has fledged thousands of biologists and conservationists into professional life across the United States and beyond.

The data rescue at Palomarin Field Station concluded on August 19. Then Point Blue chose to have the five interns and one graduate student who were residing at Palomarin, in their tight-knit Covid bubble, relocate to a safe location in Petaluma. An evacuation warning, though not an order, was in effect for the area around Bolinas, but the remoteness of the field station amplified the risk of staying longer. While it’s regrettable to miss even one day of field work, the gap in the data-set is minimalized by the sheer mass of time this research effort spans.

And it helps to know that irreplaceable information, held within many data volumes and field journals, has migrated away from the threat of loss to wildfire.

Diana Humple, Palomarin Lead at Point Blue Conservation Science, contributed to this story.

Learn more about the Palomarin Field Station online, including public visiting opportunities when the current pandemic protocols are lifted.