Update, Dec. 15, 2020: The US Fish and Wildlife Service announced that after a four-year assessment it has found the monarch butterfly deserves protection under the Endangered Species Act, but that listing is not a priority right now. The monarchs will not receive any protection for the moment, and the agency will review the decision again next year. “We must focus resources on our higher-priority listing actions,” USFWS Director Aurelia Skipwith said in a press release.

Two years ago, when volunteers counted only 27,212 monarch butterflies in the Xerces Society’s annual Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count, it meant the butterflies had crossed a threshold identified by scientists as the point past which western migratory monarchs were likely to become extinct.

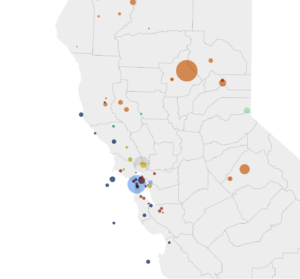

Still, after holding steady through 2019, the numbers trickling out of the count so far this fall have stunned even scientists who expected the worst. A week after Thanksgiving, with more than half of monitored overwintering sites — including all the largest ones — reporting their numbers, the 2020 count is below 2,000 butterflies. The number represents an astonishing continuation of the near-total collapse of the western migratory population of the species over the last few decades. Scientists estimate that between three and 10 million monarchs overwintered in California in the 1980s; in the late 1990s volunteers counted millions of them; more recently they counted 192,624 in 2017 and 298,464 in 2016.

“I sort of thought I was prepared for anything in terms of monarch bad news,” said Matt Forister, an entomologist at the University of Nevada-Reno. “But I did a double take.”

“We were expecting it to come in low, but not that low,” said Cheryl Schultz, an entomologist at Washington State University. “If I had to make a guess three months ago, I think we would all have been talking about less than 10,000. But coming in at less than 3,000. That’s … unexpected.”

“The big question is will they bounce back, and certainly we hope they will,” Xerces Society Endangered Species Program Director Sarina Jepsen said. “But the preliminary information we have from midway through the midwinter count is not promising at all. We really need to think about a Western United States and California that doesn’t have monarch butterflies. Because we’re getting pretty close to that.”

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

How to Help Monarchs Now

The Xerces Society needs volunteers for citizen science projects to monitor monarch populations, and the milkweed habitat they depend on. You can also add pictures of monarchs or monarch caterpillars anywhere you find them to iNaturalist.

While planting milkweed isn’t appropriate in much of the Bay Area, you can help by planting recommended nectar plants. Find out more about California pollinator conservation, including region-specific plant lists, from Xerces here.

The North American monarch butterfly species Danaus plexippus plexippus has two major migratory populations, an eastern population that migrates from overwintering sites in Mexico through the states east of the Rocky Mountains, and a western population that breeds west of the Rockies and mostly spends winters in coastal California. Non-migrating monarchs are also scattered throughout the state, country and world. Both migratory populations have declined, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service expects to decide whether to protect all monarchs under the Endangered Species Act in December 2020, after considering the matter for six years. In the meantime there are coastal areas throughout California whose monarch groves are matters of identity — Natural Bridges, Pacific Grove, Pismo Beach, Ellwood Mesa — who now face “monarchs on all their signs, but no monarchs,” Jepsen said.

Schultz, Jepsen, and several colleagues wrote in a 2019 paper in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution that the monarch might have entered a “textbook extinction vortex.” Like all insects, monarch populations fluctuate dramatically, but once a population reaches a certain low point, it becomes more and more difficult for them to recover on their own from a down year. Schultz was the lead author on the 2017 paper that suggested the threshold for western monarchs might be 30,000. When scientists gathered to talk about that number in 2016, the count had just come back at nearly 300,000. The risk of extinction seemed high then, but not necessarily imminent. When it dropped below 30,000 the next year, the question became, as they wrote in the 2019 paper, “if the experts were correct.”

“We did not expect to be here,” she said. “We didn’t want to be right.”

Western monarchs face problems at almost every stage of their lives. Habitat loss has reduced their food sources, breeding sites, and overwintering sites. Habitat degradation has made once-hospitable overwintering sites no longer a place where a butterfly can survive the winter. Climate change has dialed up heat and drought, shifting the timing of the butterflies’ emergence and migration. Wildfires, smoke, and unusual weather might directly harm them. Pesticide use has increased everywhere. In a study led by biologists from Xerces and Forister’s lab and published earlier this year in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, scientists took 227 milkweed leaf samples from 19 different locations in the Central Valley — agricultural lands, public parks, wildlife refuges, even gardening stores — and found pesticides on all of them. Separately in a 2016 paper in the journal Biology Letters, Forister correlated the rapid rise in California’s use of neonicotinoid pesticides with declines in numerous butterfly species in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“Insects have an almost unending capacity to bounce back from small numbers,” Forister said. “But one thing we’re going to learn in the next 30-40 years is [the limits of] that almost. At what point don’t they bounce back?”

“We’re still losing overwintering sites every year, including this year. They’re getting cut down, they lack protection completely, or the limited protection they have there’s a lack of awareness about.”

Jepsen said it will take a “wakeup call” and dramatic action for the monarchs at this point. One high priority should be protecting overwintering groves, she said. Though some groves, like the Pismo Beach site, are on State Parks land, there’s no restrictions on what neighbors might do. Jepsen said they watched in horror this year as a neighbor cut down critical trees adjacent to one monarch grove.

“We’re still losing overwintering sites every year, including this year,” she said. “They’re getting cut down, they lack protection completely, or the limited protection they have there’s a lack of awareness about.”

Jepsen said the state might make an effort to better protect overwintering groves, perhaps requiring a monarch specialist to consult before trees are cut down within a certain distance of a grove. She said people who live near monarch groves can also help by keeping an eye on them — going to city council meetings when development is proposed, or helping local authorities reduce pesticide use in their communities. Even people who don’t live near monarch overwintering sites can help by joining monarch and milkweed monitoring programs, finding ways to decrease pesticide use, and planting nectar plants or, if locally appropriate, native milkweed. Schultz said posting monarch sightings to iNaturalist or emailing them to her lab, from any life stage and any location in the western United States, will help researchers better understand where the butterflies go after leaving their overwintering groves, and could inform better protections.

The monarch isn’t alone in its decline, and Forister said several other California butterfly species are in an even more perilous spot. Between pesticides and rapidly warming temperatures, it’s just been a bad decade for butterflies, with even common species like cabbage whites suffering massive declines. Most alarming, Forister said, is that scientists see declines in butterflies with extremely different lifestyles and habitats, from widespread species like the West Coast lady to local specialists like the California hairstreak.

Forister said he thought off-the-charts warm and dry falls might be particularly challenging to Western butterflies.

“Over the next couple of years we’re going to learn that climate change is having a far more pervasive impact on the West than other places,” he said.

While conservationists wait for a decision from the USFWS on listing the monarch, it would also help, Jepsen said, to list the species as endangered under the California Endangered Species Act — except that in a bizarre case in late November, a Sacramento Superior Court judge found that the state’s Endangered Species Act, as it was written, cannot be used to protect insects.

The text of the law defines “endangered species” as “a native species or subspecies of a bird, mammal, fish, amphibian, reptile, or plant which is in serious danger of becoming extinct throughout all, or a significant portion, of its range due to one or more causes.”

When the state Fish and Game Commission decided in 2019 to consider four rare bumblebees as candidates for endangered species listing, a consortium of agricultural groups sued, saying that since the law doesn’t specifically name insects, it can’t be used to protect them. This left the state arguing, supported by Xerces and other conservation groups, a somewhat absurdist position, that insects are, in fact, fish under the law. The Fish and Game Code defines a “fish” as “a wild fish, mollusk, crustacean, invertebrate, amphibian, or part, spawn, or ovum of any of those animals.”

Traditionally regulators have determined that since the definition of “fish” includes “invertebrates,” that terrestrial insects can be listed as endangered. But Judge James Arguelles, who was appointed to the superior court in 2010 by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and was nominated in June for a seat on the eastern district court by President Donald Trump, wrote that the legislators clearly meant only to include “invertebrates connected to a marine habitat” under the definition of “fish,” leaving terrestrial insects out of the law entirely.

“I don’t believe the Legislature intended to leave insects out,” Jepsen said. “I believe they were working with this odd definition of fish when they passed and amended the Endangered Species Act. It’s hard to believe that a law that was passed to broadly protect wildlife in California would leave out 80 percent of all animal biodiversity.”

Schultz said it’s another rare butterfly, the Fender’s blue, that gives her hope for the monarch. When she first started working in the late 1990s, there were 1,500 Fender’s blues flying in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. They had been thought extinct through the 1980s, and were listed as endangered by the federal government in 2000. Since then, she said, public-private partners, scientists, and land managers have worked together to save the butterfly — and its numbers now bounce between 15,000-30,000.

“It takes time, and science, and partnerships, and commitment,” Schultz said. “But it’s possible.”

Clarification: This story has been updated with a clarification of the November court ruling, which states that the California Endangered Species Act allows protection of only invertebrates “connected to marine habitats.”