On a recent afternoon, tides recede at Pillar Point in Half Moon Bay, revealing what could pass for another planet. Cautiously navigating slick stone, my family hopes to spot sea slugs (very alien), and, if lucky, an East Pacific red octopus. But on this day, it’s a red leather star’s casual pose, the nervous dash of a wooly sculpin and the easy sway of sunburst anemones that have us folded over in awe. “I found a shark’s tooth!” my 5-year-old son exclaims, marveling at what is likely a crab’s lost claw, but we go with shark tooth.

Pillar Point’s reef is unique. Tidepools often run along the coastline, but Pillar Point stretches as far out as a football field on a minus-tide day and hosts at least 650 species. A sunny, low-tide day this time of year used to lure a couple dozen, maybe 100 visitors. As people have looked for socially distanced outdoor things to do in the pandemic, they’ve been drawn to the reef. Over the summer crowds grew steadily and starting in November, the first month in which mussels are considered safe from biotoxins, daily crowds numbered anywhere from 200 to 400 during low tides. That’s remained the norm through the holidays, causing concern among scientists who worry about the potential ecological impact to a place that’s long been a resilient home to many different human uses.

Alison Young, a marine biologist, arrived one day in mid-December to see an estimated 400 people. It made her nervous. It seemed most were there to harvest. That’s the other big draw of Pillar Point — you can take, not just look. With a license, it’s legal to take a certain amount of mussels, urchins, crabs, turban snails and other invertebrates. Young took a video and posted on Twitter that recreational harvesting at Pillar Point had become “completely unsustainable.”

Young co-directs the Center for Biodiversity and Community (formerly the citizen science program) at the California Academy of Sciences with Rebecca Johnson, who is also a marine biologist. They love Pillar Point’s rich, diverse habitat and generous size. “It’s one of the largest areas you can tidepool in in California,” Johnson says. Twenty miles south of San Francisco, city folk can bring a picnic, the kids, the dog, and there’s no scaling down cliffs necessary to reach the tidepools. For the last nine years, Young and Johnson have led a community science project to document life on the reef, with volunteers setting up regular ecological grids on low tide days and recording more than 25,000 observations.

They want people to discover Pillar Point and, until recently, they weren’t concerned with harvesting. But mussels don’t regenerate overnight. Research indicates it can take up to ten years for mussels to re-establish, and they’re critical to this rocky intertidal ecosystem. Seabirds rely on them for food as do sea stars, which are still rebounding from sea star wasting disease. “(Mussels) are a habitat forming species,” Young explains. “They’re sessile. They’re attached to the rock. Lots of things come and live on the mussels and inside of the mussels.”

One square yard of rock might consist of 1,500 mussels, but thousands of other marine creatures share that real estate. Mussels form thin but mighty byssal threads that glue them to rock, giving them the strength to hang on as the ocean lashes. Those threads also build necessary structure for worms, baby mussels, hermit crabs and other small species.

If large chunks of mussels disappear entire beds might weaken, making them more likely to wash away, setting off a trophic cascade in this beloved patch of coastline. Johnson says recent crowds haven’t completely stripped mussel beds, “But it’s changed,” she says. “And there are so many fewer mussels.”

On a Sunday in late December, I park about a half-mile from the reef to avoid a line 12 cars deep inching their way into Pillar Point’s dirt lot. Overflow lots down the street are also full, as are neighborhood parking spots in nearby Princeton. As I walk to the reef, I pass parents packaging their kids in puffy coats and rain boots.

It’s about three in the afternoon. Low tide is at roughly 3:30. The crowd appears 200-plus. From far away, harvesters look like fists clenching and unclenching as they bend over the mussel bed, pull mussels, stand, then get back to it. The crackle of mussel breaking from rock is constant and slowly Home Depot buckets, coolers, grocery bags, even plastic trick-or-treat pumpkins fill up.

Sara Worden, an environmental scientist with California Department of Fish and Wildlife, says it’s “exciting” to see Californians connecting with nature. It may be the pandemic’s one redeeming quality. “Harvesting in tidepools has become a thing statewide,” Worden says. “We started getting reports of this happening in southern California during the low tides back in June and July. As that began to happen we started to hear more about it occurring in the Monterey Peninsula up to Duxbury Reef and the Golden Gate.”

Mary Pepper noticed increased tidepool traffic at Dillon Beach, in Marin County. She lives in nearby Tomales and says that in the spring tidepools were filled with starfish, anemones and mussels. But around Father’s Day, she says, those invertebrates started vanishing. “I’ve been here for 35 years. I taught my kids to walk on those tidepools and I’ve never seen anything like it,” she says. “I could see where starfish had been ripped from rocks. All the rocks that had mussels on them, (the mussels) were gone.” (It is illegal to take sea stars from tidepools and it can result in a $1,000 fine.)

In southern California, Worden says, some visitors were reporting harvesting due to job loss and a need for food. But Lt. James Ober with the law enforcement division of CDFW says that doesn’t appear to be the case at Pillar Point. “The information I have been receiving is that the majority of people who are taking invertebrates at Pillar Point are doing so recreationally,” he writes in an email. And that’s exactly what Pillar Point is there for.

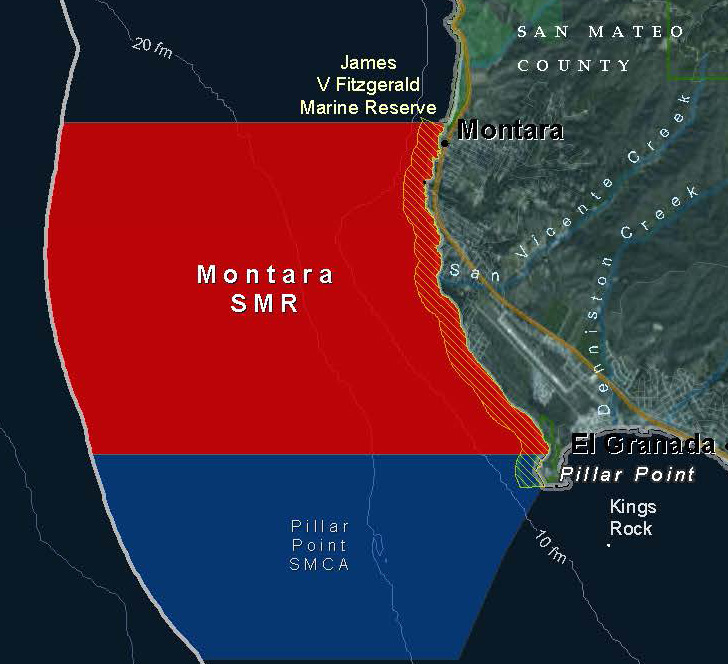

After California passed the Marine Life Protection Act of 1999, the state spent years researching and finalizing an intricate network of marine protected areas along California’s coast. From Point Arena to north of Santa Cruz, there are 25 protected areas. Some allow limited fishing, others nothing at all. The theory behind the networked protected areas was that they would create reserves for marine species to survive and continue to repopulate unprotected areas. At the Montara State Marine Reserve, which is adjacent to Pillar Point, fishing and tidepool harvesting are prohibited. While recreational explorers have visited the tidepools at Fitzgerald Marine Reserve within the Montara reserve for generations, the county closed the reef fully to all visitors at the beginning of the pandemic, and it has not reopened.

Pillar Point has been the opposite, a place that’s open to every kind of use, even during stay-at-home orders. Worden says Pillar Point’s ecological significance is no less important than protected areas, but when final decisions on boundaries were made, community input heavily influenced how to handle Pillar Point. “That reef has been a popular place both culturally and for harvesting for locals in the area,” she says. Of course, when regulators left Pillar Point unprotected no one envisioned the pressures of 2020. “We didn’t anticipate this new influx of tidepool take that’s happening,” Worden says.

Hartwell Lin recently read about Pillar Point while searching for family-friendly, COVID-safe activities. “It’s my second time (here),” Lin says, holding a modest haul of mussels in a red net. “I think a lot of people are looking for stuff to do outdoors.” Social media and blog posts in the last few years have hyped the bounty at Pillar Point and a few YouTube videos have hundreds of thousands of views.

“These are the best mussels you can get locally, and I think people have figured that out,” says Mike Volckaert, who’s been coming to Pillar Point for 30 years. “(The mussels) don’t have any sand in them, so unlike some shellfish where you chomp down and get sand, these are completely clean.”

Dressed in waders, his glasses speckled with ocean surf, Wen Tang says he likes to come a couple times a year with his kids, though, at the moment, his toddler son in a teddy bear sweatshirt shivers at his knees and begs to leave. Tang believes some newcomers might be “overharvesting on the beach,” taking more than the 10-pound legal limit on mussels. But Tang has his scale and knows the rules. “I tell the kids no tools, use your hands,” he says. Though illegal, it’s not uncommon to see people using screwdrivers and scissors to snap mussels loose.

CDFW along with the California Fish and Game Commission have fielded concerns of harvesters not following rules and avoiding fish and game wardens by harvesting at night when no one’s around.

On that late December day, turned evening, warden Max Roland stops dozens of people leaving Pillar Point to check for licenses and make sure limits and regulations were respected. He says “nearly every day” he finds someone who has taken a starfish from Pillar Point. Within an hour, he has 15 people waiting for him to write citations by flashlight as the sun slips away.

One young man visiting from New York has a Halloween bucket filled with illegal, baby crabs. Another family harvested 375 turban snails. The limit is 35. When they learn that, the group can’t help but laugh, rattled by the mistake that may cost them hundreds of dollars. “Give us some grace,” one of the women in the group pleads with Roland, offering to put them back. But Roland says the snails have already been taken and many may die, so he’s obligated to write the citation. (Later, he’ll return all the confiscated creatures to the ocean.)

Pillar Point lacks any signage indicating regulations, as well as where Pillar Point ends and the Montara State Marine Reserve begins. Johnson says that’s led to some people “trickling into” Montara where it’s illegal to take.

Worden says CDFW is in the thick of trying to respond and adapt. “We can’t stop people from going,” she says. “So how do we balance things out?”

CDFW recently created educational flyers for volunteers to pass out on busy, low-tide days. Worden says signs indicating boundaries between Pillar Point and Montara will be posted soon. Eventually, Worden hopes to have materials that help visitors understand the importance of conservation. “A lot of them are out there because they want to be outside and they love the environment,” she says. “They don’t know the turban snails they’re taking could be 30 years old.”

More pressing, Worden says, is ensuring all signs and flyers are multilingual. “I do think these outreach efforts will continue, will evolve, will get better,” she says.

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, I meet Rebecca Johnson on the reef. The crowd isn’t nearly as large as on weekends, but still well over 100 people. She points to a pool once stocked with urchins that now have few to none every time she visits.

We crouch to inspect byssal threads that cling to a rock like wet hair. Nearby, a man scrapes mussels loose with a small rake. Johnson talks about how a marine biologist in the late 1950s wiped mussels off a square meter of rock at Duxbury Reef and discovered that it took 10 years for the mussels to repopulate that space. “All of this is super variable site by site and depends a lot on conditions,” Johnson tells me later. “But it definitely takes years for mussels to return.”

If the MPA network works as designed, mussel larvae originating at Montara, or really any MPA along the North Central California coast, should travel through currents and help mussels regenerate at Pillar Point. Worden says MPAs work as an “insurance agent,” keeping marine life abundant, even in unprotected parts of the coast. CDFW is conducting a large review of MPAs and the health of their habitats in 2022. Other entities, including the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), continually monitor species at Pillar Point and other sites along the coast.

The next round of minus tides during daylight hours will happen in mid-January, then again at the end of the month. Johnson’s not sure if the crowds will continue to harvest at the current pace or what the long-term impacts of the last few months could be.

She stands near a mussel bed and looks out at the farthest edges of the reef, twirling one of her long braids and takes a few moments to think out loud. “If they can’t come here, where do they go? There has to be a way that makes it so that this is still a place people can come and enjoy. Maybe there’s restrictions on take or a moratorium on mussels for a year,” she says, pausing. “I’m going to have to figure this out.”