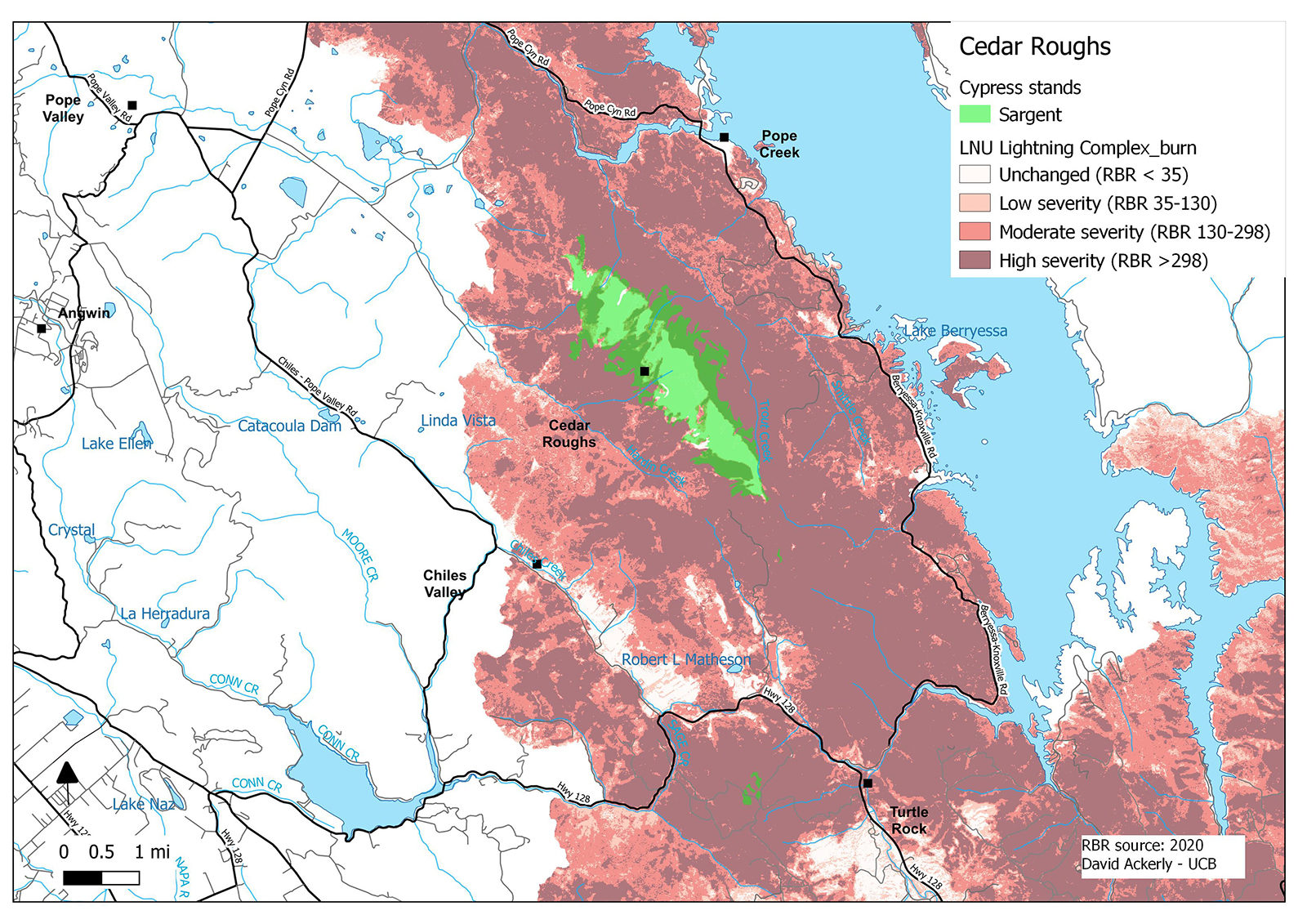

The splash of green on the ashen landscape was unexpected. Marc Hoshovsky, a naturalist retired from a career with California state agencies, was reviewing a satellite photo of areas burned in the LNU Complex fire last fall, hoping to tease out insights into its trajectory across the lands around Lake Berryessa. This landscape, on the southeast flank of the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument, had burned repeatedly in fires over the past decade. Amid the fire damage revealed in the photo, that green flag, centered on the monument’s Cedar Roughs Wilderness area in eastern Napa County, stood out like a Fresno pepper dropped on a barbecue grill’s burnt charcoal.

President Obama created the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in 2015, setting aside a compilation of federal lands scattered across the inner Coast Range on the Bay Area’s northeast margin. The monument stretches 100 miles from BLM properties along Solano and Yolo counties’ Blue Ridge north to 7,056-foot-high Snow Mountain in the Mendocino National Forest. Together, these properties conserve a region of remarkable geology and biodiversity within easy reach of the Bay Area, the presidential declaration setting aside the monument acknowledged.

Other nearby public lands include four California Department of Fish and Wildlife areas (Knoxville, Cedar Roughs, Cache Creek, and Putah Creek), shorelines of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lake Berryessa reservoir, four University of California reserves (McLaughlin, Quail Canyon, Stebbins Cold Canyon, and Cahill Riparian), and local government parks and open space administered by Napa, Solano, Yolo, and Lake County. Other private wildlands within or near the monument are protected by Tuleyome, the Land Trust of Napa County, Napa County Parks and Open Space, Solano County Land Trust, California Rangeland Trust, and Audubon California.

Marc and I travelled the Lake Berryessa region in early January to explore how the LNU Complex fire had affected the area, including the parts of the Cedar Roughs Wilderness the fire seemed to pass over. Marc knows the area well, having surveyed it repeatedly to coauthor Exploring the Berryessa Region: A Geology, Nature, and History Tour (from Backcountry Press). The varied geology, he told me, reveals how California was assembled as tectonic plates collided at the ocean’s edge and accounts for much of the monument’s varied topography and floristic diversity.

It is also a landscape shaped by wildfire. For the National Monument’s ecosystems, fire is a familiar visitor, not the disaster it can be for human settlers. Prior to the 20th century, fire renewed the inner coast range’s grasslands, swept innocuously beneath thick-barked oaks, and cleared dense chaparral, creating conditions for regrowth from root crowns and seedbanks. As elsewhere, decades of fire suppression and an extended fire season are creating conditions for larger, more damaging blazes. Much of the National Monument has been affected by wildfire over the past decade, with some areas on its dry eastern margin burning five times out of the past 6 years, the most frequent fire recurrence in the state. Marc and I hoped our visit might reveal how these infernos were affecting the area’s diverse vegetation, further exposing its geologic features, and yet had spared the Cedar Roughs.

For Bay Area residents, a convenient access to the area is Highway 128, which leaves the Napa Valley near Rutherford and continues east past Hennessey Lake, following Conn Creek, a Napa River tributary, toward Winters. The road rises along the south side of Greeg Mountain through terrain that the fire had left seared and barren. Much of the chamise chaparral had been scalded from the sunny, south-facing slopes it had once dominated. Where the fire had burned especially hot, only white, ashy skeletons of burned shrubs marked where those greasewood stands had been. The wildflowers that may germinate if winter rains are sufficient hadn’t yet emerged. A few green shoots of toyon, sprouting bravely from the shrubs’ burned remnants, provided welcome but scarce evidence of regrowth. Scorched live oak woodlands and singed grey pines with blackened bark remained in more sheltered locations.

As we drove, Marc pointed out gray and beige Franciscan Complex rocks poking through the ash. This geologic formation, so common in the Bay Area, is a mélange of sandstone, shale, graywacke, and conglomerates scraped from deep beneath the ocean and pushed to the surface by the Bay Area’s colliding tectonic plates. Also evident were expanses of blue-green and red serpentine soil, derived from mineral-laden rock scoured from the deeply buried edge of the subducting tectonic plates and surfacing in mud volcanoes that erupted along fault lines 70 to 150 million years ago. Because serpentine soils lack important plant nutrients and hold harmful minerals, endemic vegetation adapted to this infertile setting often predominates there. Our destination in the Cedar Roughs Wilderness lays atop such soil.

Just beyond the turn for Kuleto Estates winery, Marc directed me to pull into a turnout to inspect an outcrop of blueschist, a rock formed 9 miles or more beneath the earth’s surface, as sediments along the colliding plates were compressed and cooled by seawater, then thrust to the surface. Further along the road he pointed out a block of eclogite, a metamorphic rock embedded with grains of garnet, raised from even deeper in the earth’s crust.

Highway 128 crosses into Putah Creek’s watershed as it approaches its intersection with the Berryessa-Knoxville Road. The corner is marked by the Turtle Rock Bar and Cafe, a watering hole named neither for a reptile or a stone, but rather for a former owner. Putah Creek drains much of the southern part of the National Monument, carving Devil’s Gate, the site of the Monticello Dam that impounds Lake Berryessa, passing black basalt outcrops deposited by Cascade lava flows, and continuing east to supply water to Solano County’s towns and farms.

We turned north at the intersection, taking the Berryessa-Knoxville Road along Capell Creek toward Lake Berryessa. Utility workers restoring electric lines and patrols of motorcyclists enjoying the sunny day and winding route shared the road with us. Rocks exposed in road cuts revealed the interplay between serpentinite, the parent of serpentine soils, and sedimentary sandstones and shales. The sedimentary rocks, common through much of the Central Valley, are deposits that settled in submarine canyons along the continental margin to be uplifted later by tectonic plates’ ancient collisions. In Capell Creek Canyon, the fire had avoided many small vineyards and other farms. Hints of green tinted their grasslands, watered by December’s few storms. Some graceful and fire-resistant valley oaks, scattered among the farms, are reminders of the original oak savanna, which prospered where unrestricted by serpentine soils’ infertility. Where soils reverted to serpentine, knobcone pines and scrubby leather oaks, sometimes parched by the fire’s hopscotched path, were common.

As we reached Spanish Flat, Lake Berryessa emerged from behind the screen of folded hills on our right. We turned up a steep local road to a subdivision overlooking the reservoir. All but one of the development’s houses had burned, leaving only charred patios, driveways, and the vistas that once attracted homebuyers. A few hardy anglers boated across the reservoir’s more than 32 square mile surface, searching for trout and catfish. The dirty bathtub ring around the impoundment reflected the dry winter. We were surprised to see burned vegetation on Goat Island, a half mile from the lakeshore, a testimony to the distances travelled by the wildfire’s wind-blown embers. On the far shore, protected from flames by the lake’s broad expanse, blue oak and grey pine woodlands ascended the Blue Ridge toward the rocky 3,057-foot summit of Berryessa Peak, which lends the monument its name.

The highway crossed an arm of the lake and intersected Pope Canyon Road, which runs west toward our destination. The canyon’s palisades of green pillow basalt are reminders of eruptions from long ago submarine volcanos. Burned guardrail posts and charred highway signs lined the right-of-way, waiting repair. As we passed the confluence of Pope and Trout creeks, the Cedar Roughs appeared to the south. The 6,300-acre wilderness includes steep canyons, rolling grasslands, and quiet streams, crowned by the stand of Sargent cypress (Cupressas sargentii) that Marc had noticed on the satellite photo. On its often fog-shrouded heights, 1,700 feet above the lake, the cypress stand up like a flattop haircut on a 1950s engineer. The wilderness also harbors wildlife — deer, squirrels, coyotes, quail, songbirds, and golden eagles, including providing sanctuary for Napa County’s last wild black bear population.

Sargent cypress are well adapted to wildfire, which opens the evergreen’s cones and exposes bare soil for its seeds’ germination. The species, endemic to California and confined to serpentine soils, can grow up to 50 feet high, with canopy widths two thirds of its height. But where soils are especially poor and growing conditions harsh, Sargent cypress remains stunted and shrubby. In other preserves, these trees are reported to follow the fog line, along which the cypress forest can start and stop abruptly. The wilderness’ 3,000 acres of cypress are among the state’s largest stands.

Why the LNU Complex fire spared Cedar Roughs’ trees remains a puzzle. Many of the cypress are reported to be even-aged, which combined with their fire dependence suggests that the population was established after a prior conflagration. Blackened scars on the area’s slopes indicate flames may have overrun lower elevations but spared the more level heights. Perhaps those elevations were protected by a change in slope, shifting winds, or moister soil. In fact, Marc’s research in CalFire archives dating back to 1916 revealed no wildfires affecting the Roughs, a remarkable record in a region where wildfire is so common.

We planned to hike into the wilderness for a closer look at the cypress. The website for Tuleyome, the nonprofit champion for the national monument’s creation, describes a trail ascending towards the Roughs from the adjacent state wildlife area’s Berryessa unit along Pope Creek. But the wildfire’s damage had closed both the state land and the wilderness area. (Note to self: next time check the website). By next year, a new trail may extend into the wilderness along a route that the Napa County Regional Park and Open Space District and others have purchased west of Lake Berryessa’s Smittle Creek Day Use Area, but that hiking path is still under development.

As we continued west on Pope Valley Road, the fire damage diminished, replaced by vineyards and blue oak woodlands. At Pope Valley’s historic hamlet, we turn left on the Howell Mountain Road towards Angwin and the Bay Area. We climbed through a mixed forest of black oak, Douglas fir, and one of the state’s most interior redwoods groves, a dramatic contrast to the grasslands and scattered blue oaks on the area’s eastern boundary. The coastal species and windy road were reminders of the complex geology and biodiversity seen during the day’s exploration of the National Monument.