In 1965, Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Whalen, poets and students of Buddhism set out on a ritualized walking meditation, or circumambulation, of Mt. Tamalpais. Hiking clockwise as tradition dictated, they selected notable natural features along the way and assigned rituals to perform at each: Buddhist and Hindu chants, spells, sutras, and vows.

In an interview in 1992, Snyder encouraged subsequent circumambulators to be as creative as they liked, stopping at the points his trio had designated, or at others.

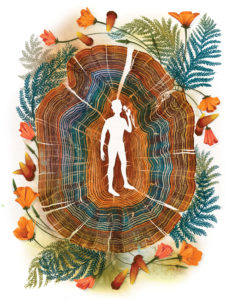

Circumambulation, an intentional, ceremonial circling of a sacred object, is an ancient ritual with roots in many world cultures. But what does it mean in modern times?

Snyder explained, “The main thing is to pay your regards, to play, to engage, to stop and pay attention. It’s just a way of stopping and looking — at yourself too.” In graduate school at UC Davis in the late 1990s, I studied poetry with Snyder. I learned from him the importance of noticing and naming where I am and what is around me, the concept of bioregionalism.

Taking up Snyder’s circumambulation mantle in the 1990s, English professor and photographer David Robertson led students on excursions of Mt. Tam in the spirit of Snyder, Ginsberg, and Whalen. One chilly March day in 1998, my boyfriend — now husband — and I joined him for the circuitous 14-mile route up, and back down the mountain, stopping to chant the same Buddhist and Hindu spells, sutras, and vows at each of ten pilgrims’ stations that the trio had done in 1965. Robertson’s intent here was to get his UC Davis Wilderness Literature students out of the classroom and into the field. Since the course featured texts by Snyder, a trip to Mt. Tam seemed a good choice.

Tagging along, I trekked through groves of coastal live oak, Douglas fir, Sequoia sempervirens, across grassy hillsides and amid fog scented with peppery California bay laurel. It took all day. And even though I was a strong and avid hiker, it was hard work. But it was worth every drop of sweat shed to be able to peek into history, retracing the steps and words of the original circumambulators. Still, I wondered: as a non-Buddhist, how did these incantations apply to me? Was it appropriative for us to invoke them? Was it enough that we wanted to learn about them and honor their traditions by performing them? When I asked Robertson, also non-Buddhist, he explained that circumambulating Mt. Tam was a way for him to create meaning for himself in relation to the natural world.

Like Robertston and his students (and me), innumerable people have undertaken the “CircumTam,” as it’s fondly nicknamed, since the inaugural 1965 trek. It’s a compelling tradition, as Mt. Tam is a beloved mother mountain of the Bay, towering in the clouds above all along with Mt. Diablo and Mt. Umunhum, reminding us where and who we are, no matter where we may be.

2020 was a difficult year for many reasons, including, of course, a global pandemic. In the year’s final days, my husband (same as my boyfriend mentioned above), our 17-year-old son, who loves to hike, and I had been cooped up at home for months. Over the summer, we had taken advantage of our unexpected time together, camping, hiking, and backpacking in California’s mountains. But winter found us housebound and feeling a bit trapped. Our annual pilgrimage to Joshua Tree National Park to stay with friends and “hike our guts out,” as I often put it, had been quashed by Northern California’s third lockdown. Like a caged coyote, I paced our little house in Davis, thinking I would lose my mind if I couldn’t do something to break up the tedium of sheltering in place in winter’s darkness.

Cue the New Year’s Day CircumTam: with a day’s notice and some adventurous pandemic podmates, we pulled together a trip for January 1, 2021, hoping to set the tone for a new year that we desperately wanted to be better than the previous one–for all of humanity.

Podmates Paul and Jennie dubbed our trip a “Circum-bobulation” because of the improvisation necessary for COVID-era social distancing, the limited daylight hours in January, and impacted parking in 21st century San Francisco Bay Area.

So we began half a mile uphill from Pan Toll Ranger Station (see: impacted parking, above). We piled out of the car on the not-so-spiritual side of the road. David Robertson had lent me a wooden-bead necklace and embroidered satin shawl, sweat-stained veterans of many a CircumTam, which he had obtained when he journeyed to Japan’s Omine ridge to learn about that region’s ancient circumambulation rituals. I donned the regalia to pay respect to David and to Gary for their mentorship, and to all the miles they’d logged in service of teaching others about the importance of linking ourselves to the land, to bioregion.

Cars whizzed by us on the road, searching for parking spots. We chanted a spell, or Dharani, intended to remove disasters. Although it was not from our culture, it was the way Snyder et al had begun their circumambulations, and it seemed appropriate, given the times; we hoped to invoke safety on our trek but also to pay respect to the many hardships faced during the previous year, and to ward off any future ones.

We cross-countried to the Old Mine Trail, and up toward what we hoped was the “ring of outcroppt rocks,” featured in Snyder’s poem, “The Circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais.”

Did we find it? No. But we did stop at a circle of rocks and stood quietly, absorbing the cold winter sun and wafting fog, and watching dried grasses shimmer in the wind. Teens Owen and Rose humored us but kept their distance.

Near Rock Springs, we found a serpentine crag adorned with an offering: a circle formed of rose petals, pine boughs, pinecones, lemons and limes. Examining this shrine, we guessed that a person longing for something had come here to ask for it. Here was more evidence of the human need to forge relationships with the land.

Trekking to a nearby lookout point for a picnic lunch with a view, we approached a huge Douglas fir and upon closer inspection saw it was a granary tree: acorn woodpeckers had drilled and filled hundreds of holes with acorns, making it a giant pantry for themselves. I marveled at the connection between a giant conifer and many small avians.

At the lookout point, we watched the stunning dance of paragliders checking their gear and sailing off the cliff toward Stinson Beach. We chatted with them, and Paul got so enthused about the sport, I thought he might buckle into a harness and leap into the void with them.

One thing about spending nearly a year in confinement is that when you emerge, everything seems new, even magical. Snyder said that the stops they designated on Mt. Tam in 1965 were “… like playing with the being of the mountain, nothing fancy about it.” Our little pandemic pod adopted this playful attitude by wandering the rest of the day, veering off the traditional circumambulation route.

After lunch, we ambled the Rock Springs trail, which steered us to the Mountain Theatre, a large amphitheater constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. As if by magic, a trio of bluegrass musicians appeared on the stage below us, tuning their instruments and playing songs. We sat, relishing the very first live music we’d heard in a year. Goosebumps marched up and down my arms, a sensation of kismet — new beginnings, hope, and possibility — that shivers through us when we’re lucky enough to feel it. I dared to breathe a little deeper.

We made our way to the West Point Inn by late afternoon and enjoyed sunshine and expansive views over the North and East bays. The teens showed us how to take socially distanced selfies, which we snapped to memorialize the zenith of our hike. Then we started back toward Pan Toll on the Matt Davis trail, arriving at dusk an hour or two later at our consecrated roadside parking spot with just enough time before dark to finish our journey by offering words of thanks to each other and the mountain for a safe day’s journey.

We hopped into our car and rolled off toward home.

With a map, a little creativity, full water bottles, and a sense of adventure, we had inaugurated a new family tradition and created some COVID-safe fun that boosted our mental and physical health during the pandemic. We also had a chance to experience ourselves in relationship with the environment, with the nature and beauty of Mt. Tam. Especially in times of distress, it’s important to feel connection, not only with other humans but with the environments around us, large and small.

Gazing at the night sky out the car window, I felt a familiar sense of oneness with all those stars, and I telescoped between feeling tiny and insignificant and feeling utterly connected to all of it.