In 1970, Jacques Cousteau’s Undersea World and reruns of Sea Hunt were at the height of their popularity, and Lynn Kimsey, a high school junior growing up in Richmond, wanted to be a marine biologist “in the worst possible way.” Kimsey spent much of her childhood outside, and when the weekends came around her mom would drive her to the San Francisco Bay shoreline, where young Lynn would wade into the mud and explore. A biology teacher at John F Kennedy High School encouraged her to collect what she found, and so Kimsey started to keep a personal record of San Francisco Bay invertebrates.

The Bay was different back then. It was dirtier and more polluted, Kimsey says. Commercial salt ponds dominated the South Bay. Trash lay in giant piles along the Central Bay shoreline. When Kimsey arrived at her collecting spots, she’d first go check all the car tires in the mudflats, because they made a nice home for worms and other creatures for the collection jar.

It was also much more accessible. There were miles of vacant lots and abandoned industrial stretches of shoreline. You could just drive right up and walk to the water’s edge. Kimsey explored beyond Richmond to other sides of the Bay, and eventually, she started taking her finds to scientists at the California Academy of Sciences for help with identification.

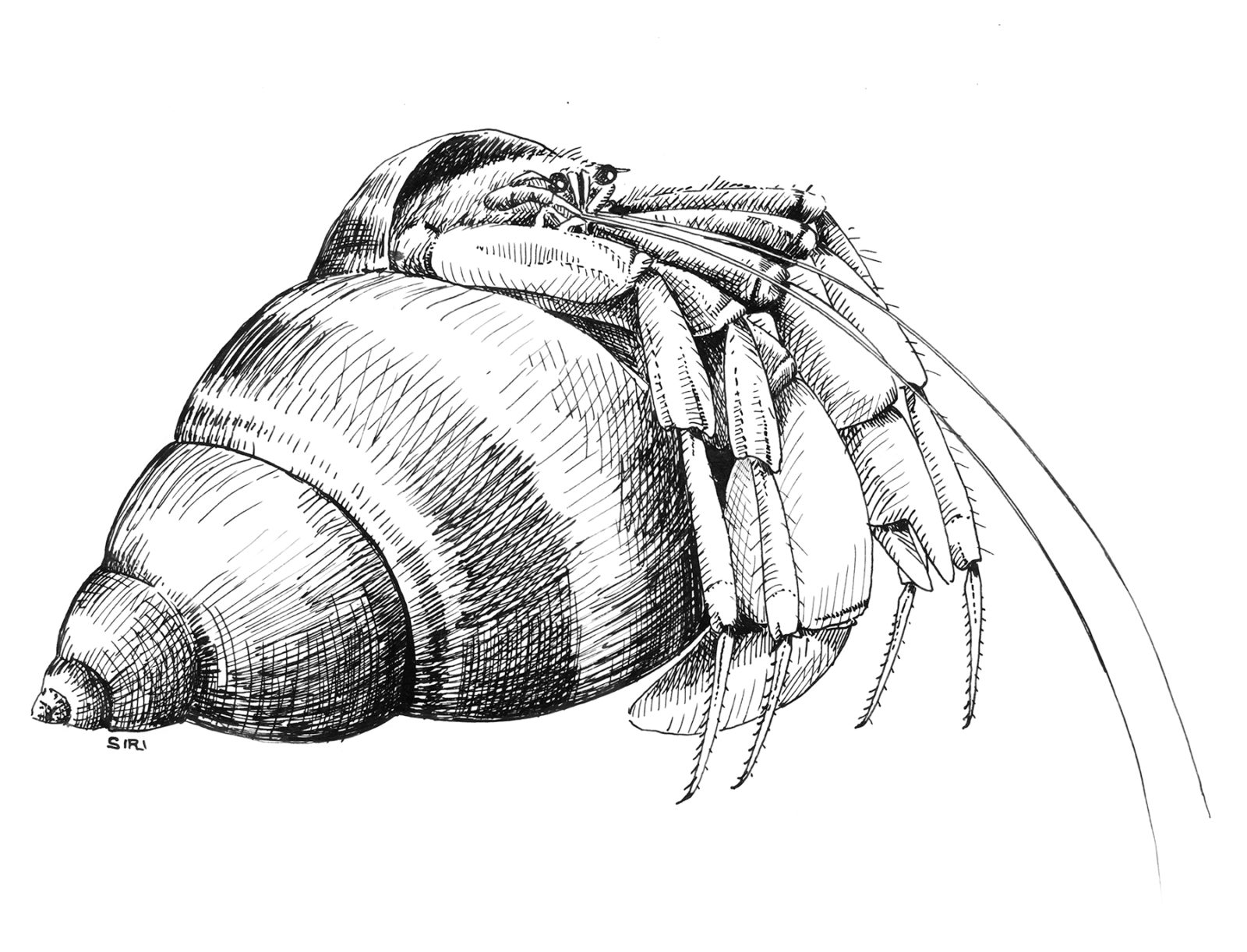

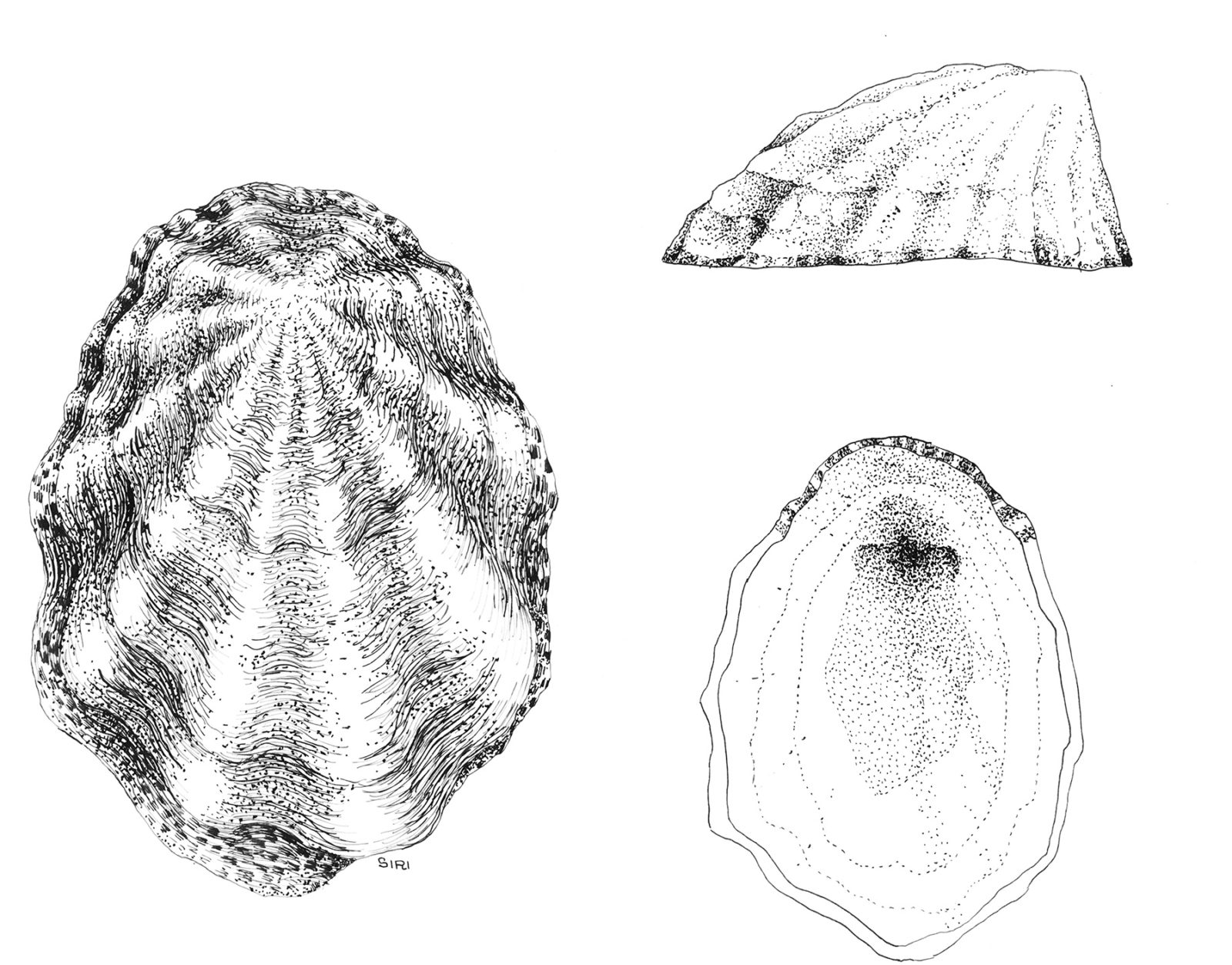

Academy scientists, especially marine biologist Jim Carlton, encouraged Kimsey to systematize her approach. So from April 1970 to May 1971, Kimsey spent a year collecting invertebrates from the mud and rocks and tires at 34 different sites around the Bay.

She wrote it all down, and identified all her collections, and then … she went back to another love, insects. Kimsey worked her way through college as a scientific illustrator, and moved on to an eventual career in research entomology. She’s now a professor of entomology at UC Davis and director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology. She’s spent the last four decades studying insects around the world, “mainly stinging things,” she says. She’s described many new species of wasps, and researched urban insects like cockroaches.

“I’ve been doing this for a very long time, and every year you learn something that an insect is doing where you smack yourself on the side of the head and go, ‘They do what?’” she says. “It’s never dull.”

In 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, Kimsey was looking through old notes and realized it had been 50 years since she surveyed the Bay as a high school student. She still had all the notes and the records. Furthermore, she knew, San Francisco Bay biodiversity surveys are surprisingly rare. You can count on one hand the major efforts to figure out what invertebrates live along the edge of one of the world’s most significant estuaries, and almost everything that has been done was limited to a few collecting spots, not the entire shoreline. The most comprehensive recent survey is 20 years old and didn’t cover natural intertidal areas like the ones Kimsey visited. In short, Kimsey saw, she was sitting on unpublished data from a 50-year-old survey that had never been done before or after.

Kimsey called Carlton, now an emeritus professor of marine science at Williams College who also got his start exploring the Bay and has spent much of his life studying invasive species, and suggested they finally publish her work. After a half-century, her record might provide a scientist a way to compare the Bay of 1971 with the Bay of 2021. “It would be nice to get somebody fired up to look at it because I think it’s a really interesting subject, and I’m not sure at this point anyone even knows what lives in the Bay,” Kimsey said by phone in July.

In December 2020, Kimsey and Carlton published the survey data in the journal Bioinvasions Records. It’s in some sense hard to know what to make of it as a record, simply because there’s so little to compare it to.

“It’s kind of remarkable for a place as famous as San Francisco Bay that we could find little information describing the intertidal life of San Francisco Bay,” Carlton says. “When Lynn brought this to my attention, this resurvey of what’s out there, well, it just hasn’t been a subject of interest for the history of the Bay. Which I found fascinating.”

In a paper in the journal Science in 1998 Carlton and aquatic bioinvasions expert Andrew Cohen concluded that the Bay might be the most invaded estuary in the world. New species have been coming in constantly since European ships started arriving en masse in the 1800s. They have arrived on ship hulls and packed with commercial shellfish and in ballast water, and they continue to arrive today. The rapid pace of introductions means it can be difficult to know exactly what’s living here now or how the Bay is changing. What was common or uncommon or there or not there in 1971 is probably different than what’s there now.

“If someone said, ‘Give me a list of all the native species in San Francisco Bay,’ I don’t know where I would point to except to say, ‘If you’ve got a few years and want to dig out a few thousand papers, you could put that together,’” Carlton says.

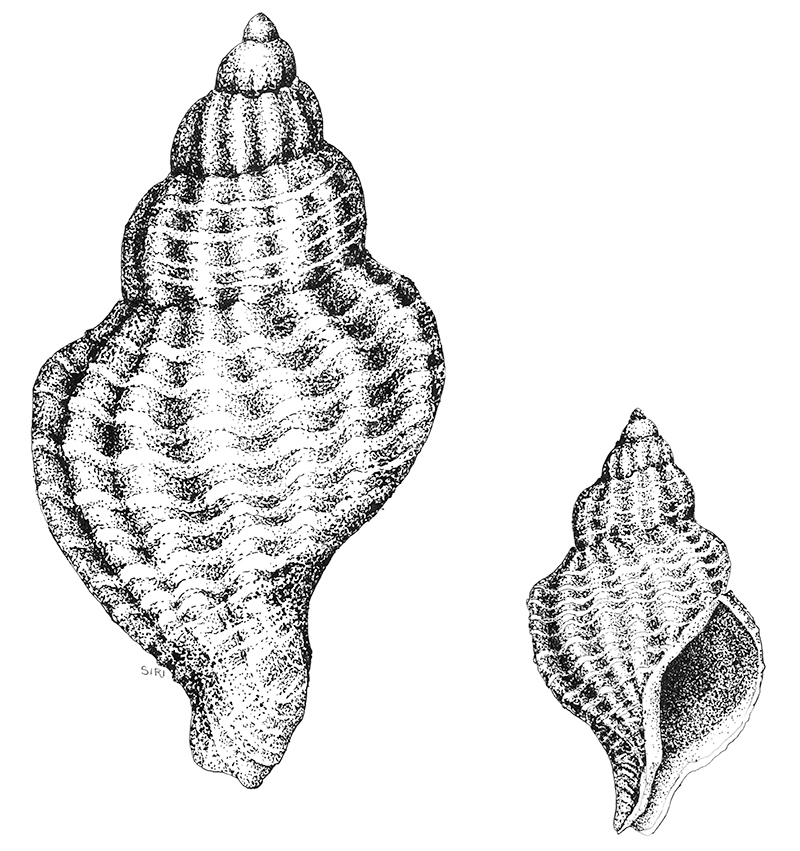

Kimsey recorded 139 species from her 34 locations. She and Carlton further sorted them by their assumed origin: native species from the Northeastern Pacific, and those introduced from the Northwestern Atlantic, Northeastern Atlantic, and Indo-West Pacific Ocean. The surveys show a clear pattern: the further you go into the Bay, the more invaded it becomes. At her most exposed two coastal sites near the Golden Gate, Kimsey found only one introduced species, a wood-boring isopod called Limnoria tripunctata. At her four sites in the South Bay salt ponds, more than half the species came from some region of the Atlantic.

Scientists have proposed a few explanations for why things are where they are. There’s a strong salinity gradient from the outer coast to the fringes of the South Bay and San Pablo Bay; it’s likewise colder close to the ocean and warmer away from it; the bottom transitions from the rocky ocean shoreline to the muddy and sandy Bayshore. But it’s not a pattern that’s been explored in the scientific literature, or updated for the 21st century. “The relative roles of physical, chemical, biological, and ecological drivers that may regulate the relative proportions of native and introduced species in the Bay system largely remain to be investigated,” Kimsey and Carlton write.

The closest publicly available guess at what lives in the Bay now probably comes from SFBay:2K, a four-year project to survey dock-fouling and bottom-dwelling invertebrates led by the California Academy of Sciences between 2000-2004. That project, now partially archived on an old Academy website and browsable in the Academy’s collections database, notes that it was the first survey in more than 40 years.

“It’s fantastic that Kimsey and Carlton eventually published their data,” Academy Invertebrate Zoology Collections Manager Christina Piotrowski, who worked on the SFBay:2K project, wrote in an email. “It’s so important that this otherwise ‘gray data’ be brought to light and made accessible so it can be combined with museum data records and cited as baseline data for future studies of the Bay.”

The challenge, Kimsey and Carlton say, will be getting someone to do that future study of the Bay.

“It’s not hot and sexy,” Kimsey says. “Hot and sexy is going to Costa Rica and playing in coral reefs. And that’s really what attracts people. Getting down and dirty in the suburbs, it takes a different attitude about a whole different subject area.”

More specifically, the challenge would be finding money to do it. It’s well-documented the many ways modern science has largely moved away from taxonomic studies and field collections and toward genetic studies and ecological modeling. Specialists who can identify the life around them are aging out of academia, and not being replaced. There are sometimes entire families of animals with only one or two people on Earth capable of distinguishing between various species, especially when it comes to less charismatic life forms.

“We don’t have modern intertidal surveys of the Bay to compare to Lynn’s, but in the bigger picture we don’t have much about the Bay in many ways, which is somewhat eyebrow raising,” Carlton says. “To me it stands in great contrast to having those questions as to what to preserve or restore, in the absence of knowing what’s there in the first place.”