Visitors to Candlestick Point State Recreation Area along San Francisco’s western bayshore typically go to the urban park oasis for its panoramic views of the Bay, East Bay Hills, and San Bruno Mountain, walking between the areas of restored grass, native plants and trees, or resting at one of the park’s picnic table areas.

But on a sunny afternoon in early October, a State Parks employee in a green bulldozer pushes heaps of debris from the park over a concrete K-rail, out of the State Park and into the official jurisdiction of San Francisco, where it can be picked up by the city’s Department of Public Works.

Informal settlements surround the sometimes bumper-to-bumper row of recreational vehicles, trucks, and cars that line the Hunters Point Expressway. The settlements are surrounded by cones, tarps, and wooden structures in some cases, granting privacy to the individuals and families living there. For the last nearly two years, that’s been a typical scene at Candlestick, where vehicle dwellings have mushroomed along the 3.2-mile park border.

In comparison to a month ago, today the road feels deserted, as more K-rail and a “ROAD CLOSED TO THRU TRAFFIC” sign have replaced the encampments that used to line either side of the road.

In a city already struggling with an affordable housing crisis, the pandemic has turned the margins of the state’s signature urban park into a home for several hundred people who live out of their vehicles. Amidst growing health and safety concerns for these individuals and the greater neighborhood, community advocates, state parks, and the city have proposed turning a small part of the park into a safer, more humane place for people to live in their vehicles. On Oct. 21, the State Lands Commission unanimously passed a proposal to allow California State Parks to sublease 312,000 square feet of parkland, about 2 percent of the overall park acreage, to the city of San Francisco for the operation of what they will call a vehicle triage center, or VTC.

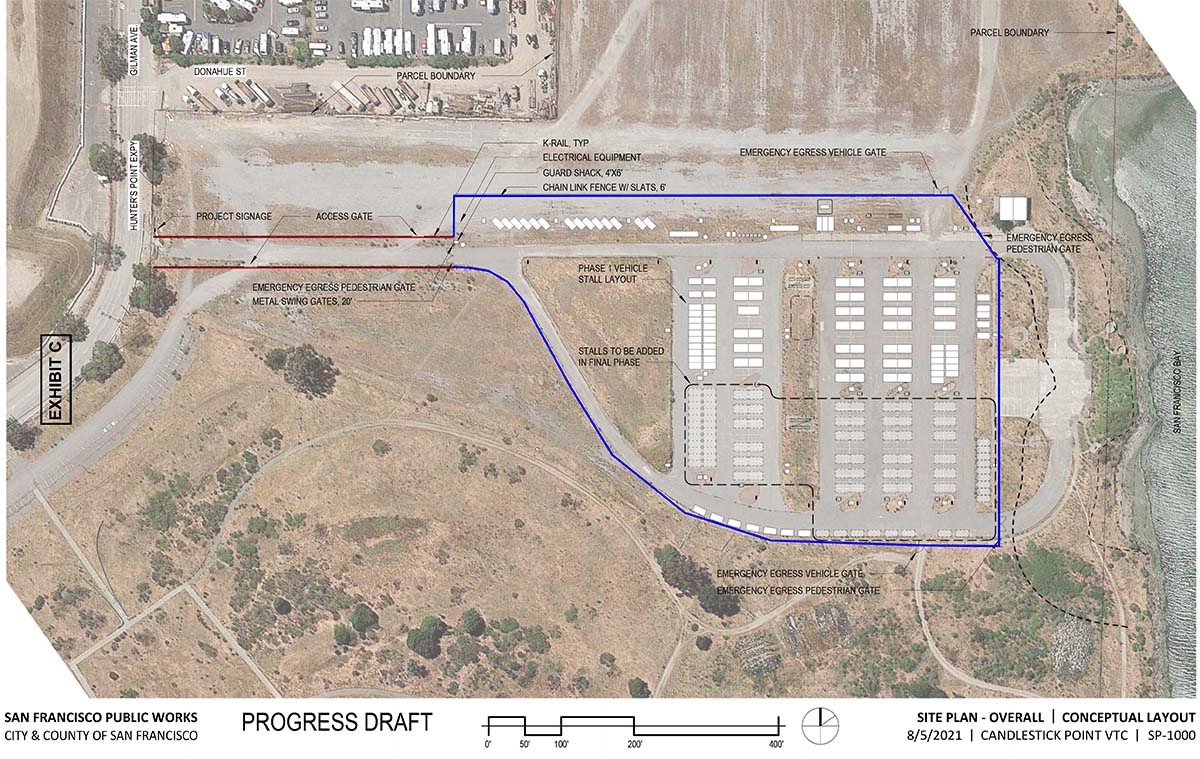

The center is slated to open this January in the State Park’s boat launch parking lot, and will run for two years. It will provide spaces for 150 vehicles to park, as well as bathrooms, electricity, blackwater pumping, showers, laundry, and a communal area, in addition to case management, housing services and 24-hour staffing and security. Setting up and running the program for its two-year term will cost the city $13.2 million.

Though San Francisco piloted another vehicle triage center in a parking lot near Balboa Park from January 2019 to March 2021, the Candlestick VTC will be the first time a state park is officially used to shelter people who are unhoused. The Candlestick project stretches the boundaries of what has traditionally been considered proper use of public lands, pointing to an evolving conversation around how the “public trust” can be used to combat economic and racial inequality. It also reveals the fragile nature of trust and complex web of stakeholders in the green spaces of Bayview-Hunters Point, where community activists have fought pollution and city neglect for decades.

“If peace is found on common ground, then equity is found on public lands,” says Anthony Khalil, the inaugural environmental justice advisor to the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, and a food sovereignty manager at Bayview-Hunters Point Community Advocates. Khalil says that while the pandemic has created a “unique and endemic situation,” he sees the VTC as an “opportunity to showcase” how public lands can support the needs of community members most affected by the housing crisis and historical inequality by putting them at the forefront of decisions about how public land is used.

Though the effects of the affordable housing crisis are squeezing people across the state, there are few places in California where state parks, extremely costly housing markets, and histories of environmental racism intersect as closely as they do in Bayview-Hunters Point. The global pandemic has forced jurisdictional agencies and the community to work together in ways they never imagined.

“This is not something that normally I thought I would be dabbling in in my career with State Parks,” said Gerald O’Reilly, the San Francisco Bay sector superintendent of California State Parks.

In addition to trail work and grounds upkeep, park employees like O’Reilly have turned their focus to addressing vehicular encampments near the park, whether that includes putting a K-rail along the park’s boundary to keep cars and RVs from entering the park, or meeting with community stakeholders to discuss how to best aid individuals living out of vehicles.

Vehicular encampments were increasing in San Francisco even before the pandemic. From 2017 to 2019, two thirds of newly unhoused people in San Francisco were sleeping in vehicles. As of August 2021 there were 677 RV and vehicle dwellings — slightly less than two-thirds of the city’s total vehicle dwellings — recorded in District 10 (which includes the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood).

After conducting a point-in-time count of unhoused people in the neighborhood in March, a working group of community organizers and stakeholders began workshopping solutions to connect them with much-needed access to sanitation facilities, showers, laundry and other services, including resources to exit homelessness. The result took shape as a vehicle triage center in Candlestick Point State Recreation Area.

However, now that the VTC proposal is moving forward, some residents are resistant — calling out a chronic lack of resources in the historically Black neighborhood, and asking why one of their coveted natural spaces should be used for the center.

Once bountiful wetlands, by the 1970s Candlestick Point was an informal dumping ground. Community members, alongside California State Assembly Representative Art Agnos, successfully advocated for the state to purchase the land and develop its first urban state park, which opened in 1978. But Candlestick has been underfunded from the start relative to more-visited state parks. In 2008 and again in 2012, the state threatened to close the park to help reduce state budget deficits.

“There’s very little access from the community to the actual open space,” said Patrick Rump, Literacy for Environmental Justice Urban Stewardship Director, citing a lack of trails, sidewalks, signs, and public transit near Candlestick State Park. “Some of the tragedy of what’s occurred during covid out here is that you already had a park that had some accessibility issues and they’ve just been exacerbated.”

Today, park accessibility continues to decrease as vehicular encampments have taken over sidewalks. On-site parking lots and bathrooms remain closed after over 18 months. The park is open, but O’Reilly said fewer visitors have come.

VTC proponents hope the new designated parking area will address accessibility issues, relieve inhumane living conditions, and reduce environmental impacts in the surrounding areas.

“By repurposing underutilized public space, we’re going to be able to provide something that is healthier and more dignified for people experiencing homelessness and living in their vehicles, but also an ability to clean up that area from a physical environmental perspective,” said Emily Cohen, the deputy director for Communications and Legislative Affairs at San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

Lena Miller, CEO of Urban Alchemy, a nonprofit that ran the Balboa VTC’s day-to-day operations, acknowledged that vehicle triage centers are a temporary fix — but a needed one.

People don’t think about what living in a vehicle entails, she said: “having to shit in a jar in your car on the street, having rats cohabitate with you, not being able to wash your hands, being exposed out on the street, being raped.”

The center is key to fully reopening the rest of the park’s assets, including parking, bathrooms, and campsites, O’Reilly said.

But one group of residents is unhappy with the prospect of a center, and enlisted the Golden Gate University Environmental Law and Justice Clinic to speak against it at the State Lands Commission meeting.

“Everything that no one else wants in the city is dumped in our community,” said Shirley Moore, vice president of the Bayview Hill Neighborhood Association, at a neighborhood association Zoom meeting in early October. The group is advocating that mobile dwellings be spread throughout other parts of the city.

In various meetings with city and state officials, association members expressed frustration fueled by the historical and ongoing lack of green spaces in the area, opposing the plan on the basis that it would limit residents’ access to the park.

But Michelle Pierce, the executive director of BVHP Advocates and a member of the VTC working group, says spreading out into the city has never been a realistic option.

“If you’re going to fight this particular solution, you’re saying you’re happy with the status quo,” Pierce said. “Move those people to the Presidio is not a solution. These are not barn animals.”

When it comes to using the public park, Pierce added, it raises many questions, especially regarding race and class.

“Who gets to use what spaces, and in what ways, and why is one person’s way of engaging with the parks more appropriate than another person’s way of engaging with the park?” Pierce asked. “Shouldn’t we all be allowed to develop our own relationships with nature, and what it means to us?”

The proposed VTC site is a barren parking lot, a shell of former days when it was populated with rowdy tailgaters donning red and gold jerseys before 49ers games in the now-demolished stadium. When the team left for Santa Clara, so did city resources dedicated to neighborhood upkeep, many community members say. Funding and attention returned with proposed developments, which include 13 miles of new trails and parks along with 12,000 homes. To residents who have long felt overlooked, the conditional nature of the attention, with resources tied to development and parks and trails built seemingly for the benefit of future residents, not current ones, has led to further distrust and fear of gentrification.

“It’s continuously always project, project, project,” Khalil said.

A 2020 MTA Report notes that investments in roadway infrastructure and transportation are tied to development milestones, meaning “the anticipated delivery of new transportation services is now unclear due to delays in full remediation of contaminated soil.” This follows the closure of many Bayview-Hunters Point MUNI lines during the pandemic, cutting off access to essentials such as grocery stores, Pierce said.

Now, as the developments have stalled due to the pandemic and the failure to properly decontaminate the former shipyard, the city’s interest in the southeast bayshore waned again, neighborhood advocates say.

“When the brakes screeched to a halt on this development, it felt like the city’s attention to this part of the city of San Francisco just kind of vaporized,” Rump said.

However, despite closures and delays, the pandemic has the potential to produce one thing: new partnerships.

“Without the pandemic, we would have never been put in each other’s paths,” Pierce said of the working group.

Though the center and its services will be temporary, O’Reilly said he believes that it will offer an opportunity for the park to create a lasting partnership with the city.

Instead of paying rent for utilizing public land, during the center’s tenure the MTA will provide regular parking enforcement in the neighborhood, police will conduct daily patrols of the park and the Department of Public Works will remove debris at least three days per week in the surrounding area.

An arrangement like this is “uncommon,” said Cohen, who sees the center as a “really important nexus between housing justice and environmental justice.”

“Building these relationships so that we can be in a position to compassionately respond to this pending crisis is important,” Bayview resident Chris Whipple said.

Individuals like Khalil still champion the necessity of broader systemic change through what he called “self-determination” of public lands, building beyond a “broken history of triage.”

To Khalil, the long-term solution is putting underserved people and community-based organizations at the helm of decisions being made about public lands, including funding and the highest leadership positions.

“Time will tell on what’s the next stages of this,” he said. “I think it’s a real test of compassion, empathy, intersectionality and all that, and putting it on the line. But what can we change culturally on the larger scale?”