Ever since the 1930s, when an improbable remnant colony of sea otters was discovered off the rugged Big Sur coast after more than a century of intensive fur hunting, Californians have worked to bring the animals back from the edge of extinction. Their numbers have grown from around 50 individuals to a little under 3,000, where the population has hovered for some years, remaining threatened under the Endangered Species Protection Act. While the otters no longer face imminent extinction, a growing movement to bring them back to northern California waters could spell revitalization not just for these furry mammals but for entire communities of life—our own included, as Californians collectively look toward coastal ecosystems for climate solutions.

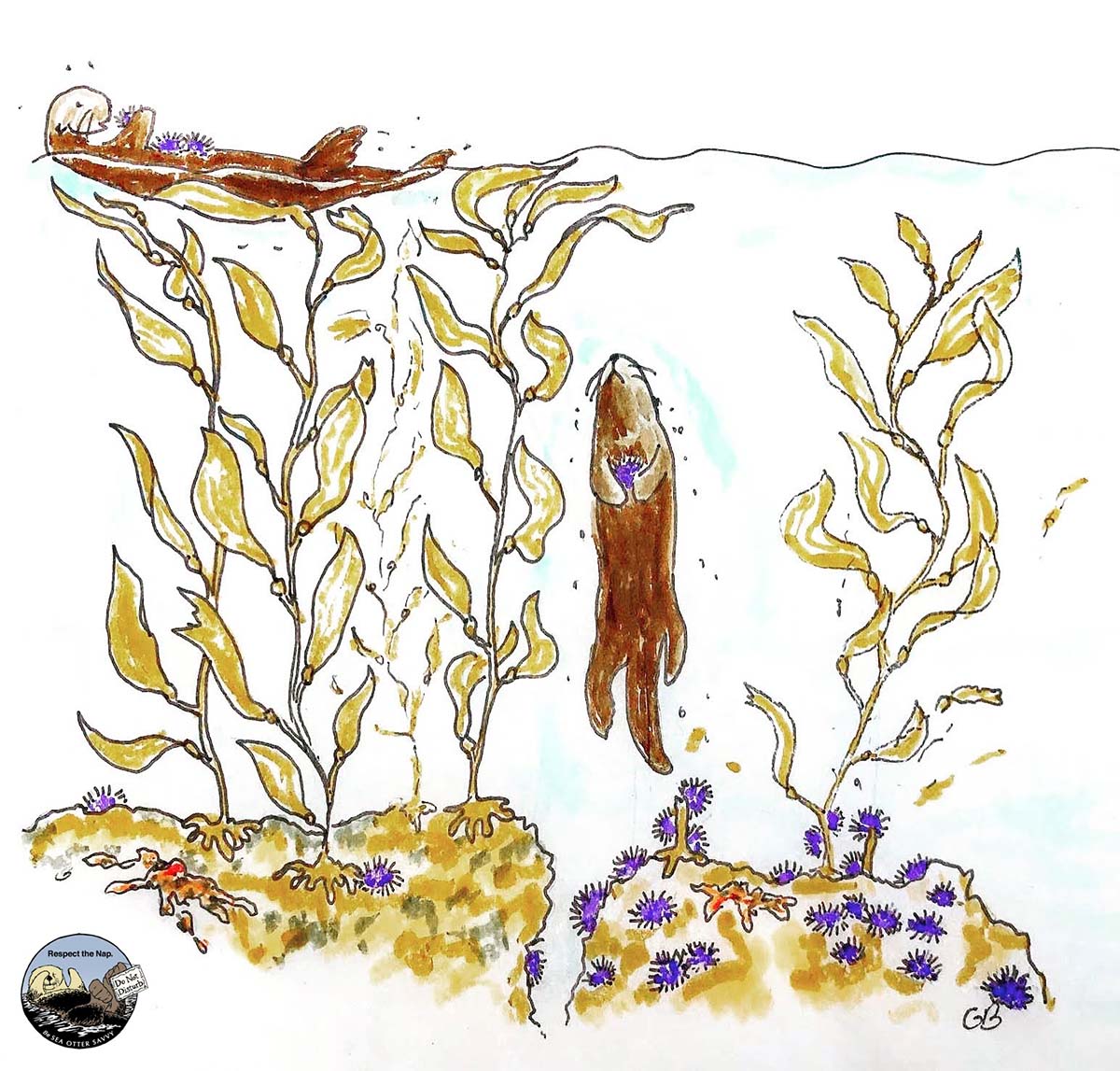

For thousands of years, sea otters were the keepers of kaleidoscopic communities of life along the California coast. Otters plucked and ate kelp-grazing urchins, and the kelp grew steadily, harboring a dazzling diversity of life from tiny invertebrates to fat harbor seals. The sea otters’ near-extinction in the early 1900s meant not just the potential extinction of a single species, but the extinction of ecological interactions—the extinction of relationships. Even now, in the places where sea otters remain locally extinct, marine heatwaves and mass sea star die-offs have toppled the ecological balance of kelp forests—95 percent of California’s kelp stands have disappeared in the last 10 years—while in places where otters have returned, they have boosted the health of surviving remnant kelp patches.

For the last five years, the California sea otter population has held steady or slightly declined on the central coast. But the otters haven’t been able to expand their range beyond the core region from San Mateo County south to Santa Barbara County, and their current numbers are still far below what is necessary for a truly sustainable population. Now, recent research on otters’ ecological interactions shows a pathway to help them expand into their former territory.

In 2013, Sonoma State University biologist Brent Hughes discovered a connection between sea otters and the seagrass beds he was studying in Monterey Bay’s Elkhorn Slough. In places with high levels of nitrogen from agricultural runoff, algae will begin growing on seagrass, preventing it from photosynthesizing and eventually killing it. An invertebrate called Taylor’s sea hare helps graze the algae down. “These animals are amazing,” Hughes says in a recent webinar hosted by Marine Conservation Institute, showing a photo of a small sea slug with green dappling across its body. “They’re like little lawnmowers.”

Hughes’ study showed that eelgrass in Elkhorn Slough had started to rebound—despite heavy nutrient loads and extreme algal blooms—right around the same time that sea otters were being reintroduced to the estuary. It turned out the sea otters were devouring the local crabs, which were predators of the sea slugs and other algae-eating invertebrates. By keeping the crab populations in check so that the “lawnmowers” could do their work, otters were reviving eelgrass ecosystems. A follow-up study by Hughes’ team demonstrated that seagrass beds expand in the presence of sea otters, and in 2021 Hakai Institute released a paper showing that sea otters increase the genetic diversity of seagrass.

As in any good relationship, the benefits are mutual: otters help seagrass beds thrive, and in turn seagrass supports otters, providing rich food and restful habitat where otters can escape strong currents and large ocean predators like sharks. “Of the habitats available to otters,” says Hughes, “the highest concentration of sea otters in California is in Elkhorn Slough, and within that habitat the highest concentration is in seagrass beds.”

When he received a Smith Fellowship for conservation, Hughes was able to springboard off of his observations in Elkhorn Slough, exploring how sea otters might influence other estuaries elsewhere in California. In 2019, Hughes and several colleagues published a study suggesting the estuarine habitats in San Francisco Bay could theoretically support as many as 6,000 sea otters. This report is spurring a growing movement to return otters to their historic range in the San Francisco Bay Area—a movement that could revive not just otters but entire ecosystems.

If sea otters and seagrass meadows thrive together, what’s keeping the otters from taking matters into their own paws and pushing further into their old estuary territories? Between their current range and the estuaries of Northern California, “there’s not a lot of kelp habitat for them to use as migratory jumps from kelp patch to kelp patch,” Hughes explains, “so there’s not a lot of opportunity to find refugia from great white sharks.” Heather Barrett, the science communication director for the nonprofit Sea Otter Savvy, which works to reduce human-otter conflict, describes the coastal journey northward as a “shark gauntlet” that bars the entrance to estuaries in Northern California.

Biologists have also learned that otters are extraordinarily “site loyal,” which means that it’s tricky to pluck them up and set them down in a new location. In 1987, an experimental translocation program began on San Nicolas Island, where otters were relocated to the remote Channel Islands from the mainland California coast. Though a small population of sea otters remains there today and is gradually growing, most otters returned to their original territory, leading to the translocation program being terminated in 2012. However, young otters are more likely to stick to a new territory, and a groundbreaking program at the Monterey Bay Aquarium has succeeded in releasing more than 35 orphaned otters into Elkhorn Slough. Here, the rescued pups—which have learned how to succeed as otters from surrogate otter mothers at the aquarium—have survived just as well as their wild counterparts, and they now account for the majority of otter population growth in the slough over the last 15 years. It’s a success story that could easily scale up once the right pieces are in place.

And the pieces, it seems, are beginning to click into position. “Forward momentum right now is huge,” says Andrew Johnson, who spent 20 years pioneering the Monterey Bay Aquarium surrogacy program and now works with Defenders of Wildlife. In Oregon, an Indigenous-led nonprofit called the Elakha Alliance is evaluating the feasibility of bringing sea otters back to the Oregon Coast. At the same time, Congress has ordered the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to explore sea otter reintroduction as a species management strategy across the broader West Coast. Longtime otter biologist Tim Tinker spearheaded the Elakha Alliance feasibility study and is now also helping to advise the report for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The synchronicity of these two efforts—and the congressional pressure to finish the West Coast report this year—brings the question of otter range expansion into near focus after years of slow groundwork.

Meanwhile, Johnson has been in conversation with the Aquarium of the Pacific and SeaWorld to coordinate preliminary planning for new surrogacy facilities for orphaned otter pups, although Covid-era funding priorities have slowed the work. If established, these facilities could help raise more orphaned pups than the Monterey Bay Aquarium can manage alone—pups which could, theoretically, be released into new estuaries when the time is right. “I think it’s all going to hinge on surrogacy,” Johnson says. “Continuing to take a passive approach may never achieve recovery of the population, at least not in our lifetimes.”

If otters are reintroduced into their historic range, where will they live? Although Hughes’ 2019 study suggests that San Francisco Bay could sustain huge numbers of sea otters (and historically it did, as otter bones found in middens from Indigenous village sites along the Bay suggest) the reality of bringing otters into the Bay is complicated. High shipping traffic, nearshore development, and toxic levels of urban pollution might make it a tough entry point for young otters. Hughes and Tinker are working to develop models that will predict how well smaller Bay Area estuaries like Drakes Estero and Tomales Bay could support otter populations. As a graduate student researcher at San Francisco State, Jane Rudebusch designed a map that analyzes potential sea otter reintroduction sites by overlaying promising habitat across a myriad of risk factors, from Indigenous clamming sites to areas with high boating traffic.

Returning sea otters to places where they’ve been missing for a hundred years is a complicated conversation. The greater Bay Area is a different place than it was a century ago—people from all walks of life depend on the coast for their livelihoods, from oyster farming to outdoor recreation. Any project that moves forward with sea otter reintroduction will need to honor these complicated layers of industry and economy; without consensus, range expansion plans are likely to stumble. The nonprofit Sea Otter Savvy is currently gathering feedback in a stakeholder survey, which can be found on their website.

Voices from all sides are important: in Southeast Alaska, the successful return of northern sea otters to much of their historic range has sparked debate and frustration among fishermen who argue that the otters compete for lucrative urchins and shellfish—no small inconvenience, in an industry valued at $10 million. However, Hughes says, “what we’ve seen up north is that otters regenerate habitat” in a way that might bolster biodiversity to benefit both ecosystems and economies. “They eat urchins and bring back kelp, and they might offset any negative effects on fisheries.”

In the time ahead—a time punctuated not just by the possible return of a keystone predator, but also by marine heat waves, storm surges, ocean acidification, and other climate disruptions—looking toward the future of fisheries will likely be a necessary reckoning, regardless of where sea otter range expands. The ocean is overstrained, and while sea otters can do a lot for us, we might also need to redefine what’s sustainable for ourselves and future generations on the California coast. It seems that the right order of operations is to heal first, and to find a new balance afterward.

It is important to note that the return of sea otters to northern California can’t be simplified as a return to the way things were. It’s possible, instead, that otters might help us address the way things are. Intact ecosystems—in particular, intact ocean ecosystems—play an enormous role in mediating the effects of climate change. Studies indicate that coastal ecosystems sequester ten times more carbon than tropical forests, and can hold that carbon for millennia longer than terrestrial ecosystems can. But these “Blue Carbon” habitats are among the most endangered ecosystems in the world. We are losing almost two percent of seagrass meadows every year—two soccer fields worth every hour. If otters can revive estuaries elsewhere along the California coast as efficiently as they’ve rebalanced Elkhorn Slough, then they may well be not only ecosystem architects, but “unsung climate heroes,” too, says Marine Conservation Institute President Lance Morgan. Here on the West Coast, where the effects of climate change are increasingly visible and visceral, this is no small thing.

Treating our coastal ecosystems not just as casualties but as active agents in tackling climate disruption requires an act of reimagining. In restoring this lost balance, it seems we have the opportunity to summon not just an old world, but a better one.