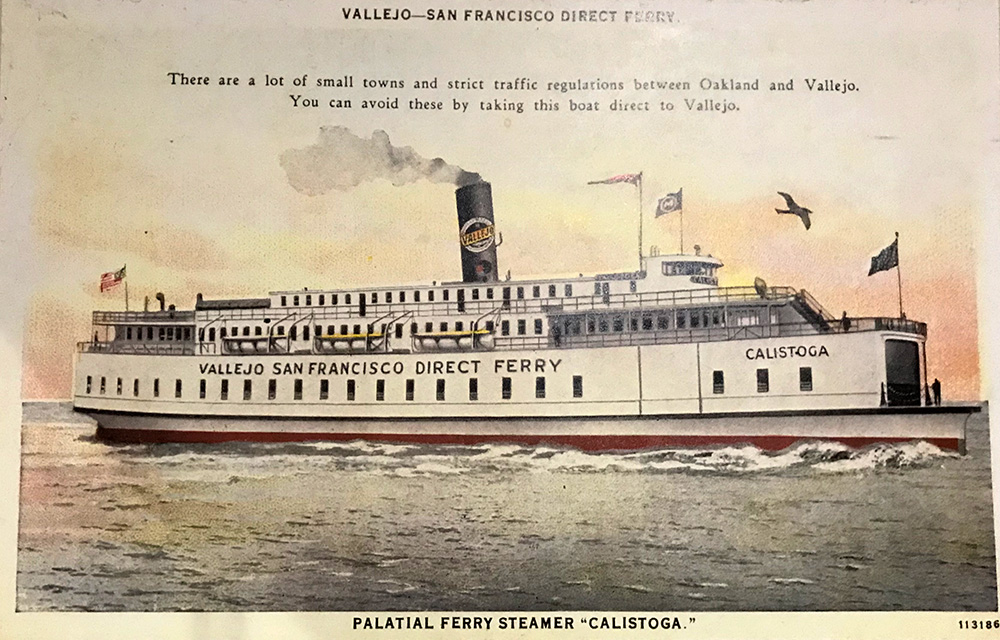

Before the bridges, there were ferries. In the mid-1930s, before the Golden Gate and Bay bridges were completed, over 50 million people crossed the Bay by ferry annually. And yet, to promote use of these massive public works projects, the California State Legislature banned passenger ferry service across the Bay, leading to the elimination of ferries by the mid-1950s.

Fortunately, today the Bay is once again transected by daily ferries. What’s more, they’re environmentally friendly, relaxing, and cheap—a trip from San Francisco to Richmond, for example, costs just $4.50 for a beautiful 35-minute journey. So for the past several months, I’ve been exploring what I can see of the Bay by ferry.

By boat, I’ve learned, you get a sense of how thoroughly—for good or ill—people have manipulated San Francisco Bay’s 400 miles of shoreline, building landfill, ports, railroad terminals, channels, bridges, and extensive military and industrial infrastructure.

But you also see the Bay’s transition to a more “natural” state, healthier for nature and for people. Restoration efforts are visible as tidal wetlands, redeveloped shoreline parks, and the Bay Trail.

There is magic in boarding a ferry at San Francisco’s Ferry Building. From there, I can transport myself to other worlds, just across the Bay, and explore them on foot or by bike. Here are five places that delighted me.

Alameda: An island of contrasts

Arriving at Alameda’s Main Street Ferry Terminal, I’m reminded that Alameda, like Oakland across the channel, is a busy port. Cargo ships with containers stacked high dwarf the ferry. Commercial, military and government ships are festooned in scaffolding for repairs. Dock workers zip supplies around by bicycle. I’m mesmerized watching this activity, and disoriented by the scale of the human-built environment. At the ferry terminal, a short stretch of the Bay Trail lined with sculptures describes Alameda’s maritime history (one of the sculptures, a coiled-up rope, has been aptly nicknamed the Doo Doo Sculpture).

But Alameda is an island where nature and green spaces co-exist with the working shoreline.

On Main Street, I come upon the nonprofit Ploughshares Nursery, a native plant nursery. Here also live rescued domesticated pigeons and doves. Next door is the Maker Farm, a ramshackle collection of artists’ studios and public maker spaces in shipping containers. These two sites, and the Farm2Market next door, are part of the Alameda Point Collaborative (APC), a nonprofit organization that helps unhoused people find supportive housing in the former military barracks nearby.

At Farm2Market, volunteers invite me to wander through the orchard and beds, abundant with kale and other autumn veggies. Farm2Market is a community-supported agriculture site that trains and employs people who are now living in APC-supported housing. I’m struck by the contrasting juxtaposition of these natural spaces, built on human compassion and optimism, with the nearby port and military structures.

The Main Street Linear Park, a green space lined with young redwood trees and rainwater swales, appears to be developing into a beautiful greenway. It takes me to Encinal Beach, a wilder place. Here, Alameda’s shoreline offers beaches and a rocky breakwater wall where great blue herons hunt. On a concrete float offshore, harbor seals have hauled out to rest. The shoreline also offers an adventure in rambling and scrambling over rocks at low tide and through residential neighborhoods, as sections of the Bay Trail between Encinal Beach and the popular Crab Cove and Crown Memorial State Beach do not yet connect.

I’ll return another day to follow the Bay Trail south from Crab Cove to the Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary, one of the Bay’s last remaining salt marshes. You could also visit the USS Hornet, a decommissioned aircraft carrier, and catch a ferry from Sea Plane Terminal nearby.

Richmond: A city taking back its shoreline

As the ferry approaches Richmond, I see another industrial shoreline—here, ships are built and autos assembled, among other industries. Next to the ferry terminal, though, is a dramatic silvery sculpture called Changing Tides, inspired by the eel grass that creates habitat for marine wildlife. There, clear interpretive and wayfinding signs give me a friendly welcome.

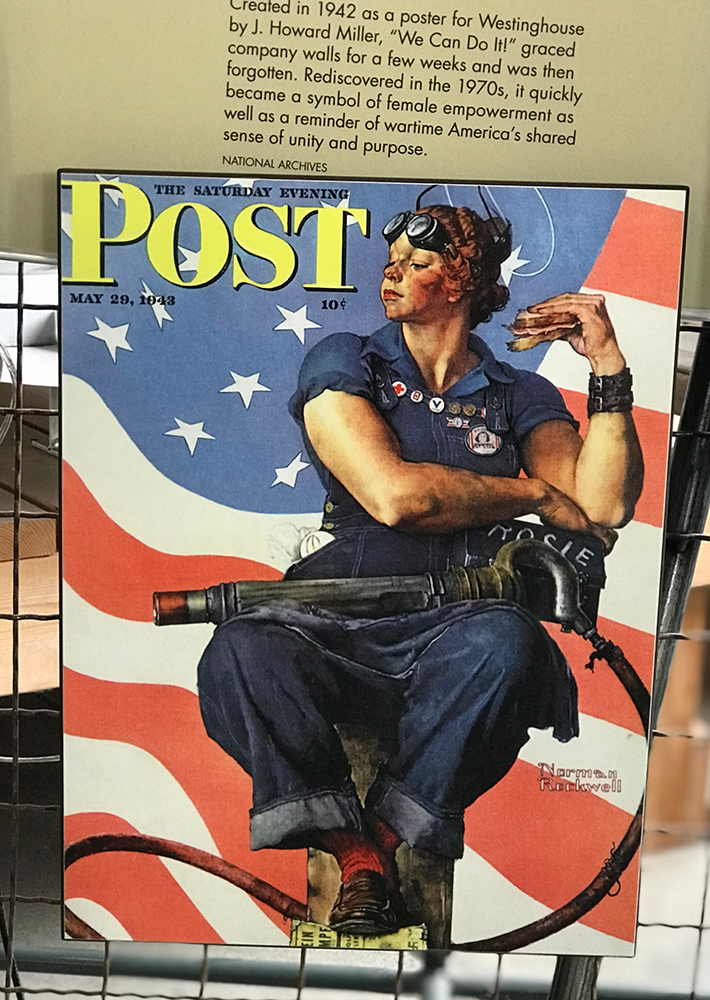

Here, the shipbuilding industry attracted women and people of color into the workforce, helping make Richmond and the Bay Area more diverse. This social history comes to life at the free Rosie the Riveter World War II/Home Front National Historical Park Visitor Center, just east of the ferry landing. It’s well worth a visit.

But Richmond carries the weight of decades of environmental contamination from these industries, too: extensive fencing and danger signs interspersed along the shoreline’s new housing development. There are many places apparently unsafe to tread.

I learn more about Richmond’s history through interpretive signage along the Bay Trail. The city has developed more of the Bay Trail and connections than most other Bay communities: 36 miles of trails with just 6 miles of gaps. The paved, accessible Marina Bay Trail section offers views of Angel and Brooks Islands and the San Francisco, Berkeley, and Oakland skylines, as well as frequent benches, picnic tables, and clean restrooms (a free trail guide is available at the Rosie the Riveter Visitor Center or online here).

Further along, the developed shoreline transitions to a more natural tidal wetland. Since the tide is low, I veer off the paved trail at Shimada Park to walk along the beach towards the mudflats of Meeker Slough. It teems with shorebirds—snowy egrets, great blue herons, double-crested cormorants, coots, American avocets, curlews, willets, and others. Bikers or hikers can follow Meeker Slough towards El Cerrito and Albany.

I head back towards the ferry along the Meeker Tidal Creek, where ducks and other water birds forage along exposed mudflats. At the marina I come upon a black-crowned night heron, out early for dinner (the Assemble Marketplace next to the Rosie the Riveter Visitor Center serves up human food and drink, too). That evening, the relaxing return ferry ride to San Francisco rewards me with a beautiful sunset and lit-up SF skyline.

Vallejo: California’s first capital

The fast ferry from San Francisco to Vallejo takes almost an hour, but I see so much along the way, both natural and human-made. Barely visible is the north shoreline of San Pablo Bay, eight or so miles away. Along the way I get to see Mt. Tamalpais, Mt. Diablo, and so many magnificent bridges: Bay, Golden Gate, Richmond-San Rafael, and Carquinez. Plus islands—Alcatraz, Angel, and less famous ones like East Brother Island, off Point Richmond, with its historic lighthouse.

The ferry slows to navigate the channel between Mare Island and Vallejo, which is at the mouth of the Napa River. The Carquinez Bridge looms in the distance. To my right, gulls and cormorants perch along the breakwater, while houses on stilts perch above the water. To my left, Mare Island’s wetlands provide a natural foreground for the dilapidated military structures dotting the island and the massive military ships in the port beyond.

Upon arrival, I’m met with art. Just outside the ferry terminal, a mosaic totem pole known as Connections promotes the Vallejo Art and Architecture Walk, a self-guided tour through the historic downtown. (Look out for the Flaming Lotus Girls’ SOMA sculpture, the birds-eye view Gateway to Vallejo mural, and the storied Alibi Clock). In one of the many active studios scattered throughout downtown, an artist happily fills me in on Vallejo’s thriving arts community.

As the state’s first capital, briefly, Vallejo played an important role in California’s transition from the Mexican land-grant period of the early 1800s, to statehood in 1850, and to the first US Navy installation on the West Coast, the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, in 1854. I learn more about this history in the quirky Vallejo Naval & Historic Museum, located in the city’s original City Hall. Around the corner, I’m treated to an impromptu tour of the restored Beaux Arts-style Empress Theater by a friendly woman working at the ticket booth.

Wandering back to the ferry terminal, I imagine how this concrete-and-grass waterfront could be restored to a more natural, wildlife-supporting shoreline, as I’ve seen elsewhere along the Bay. I plan another ferry trip to visit Mare Island next winter, when over a million shore and water birds will be migrating through or overwintering in this important wetland.

Tiburon: History, wildflowers, and stunning views

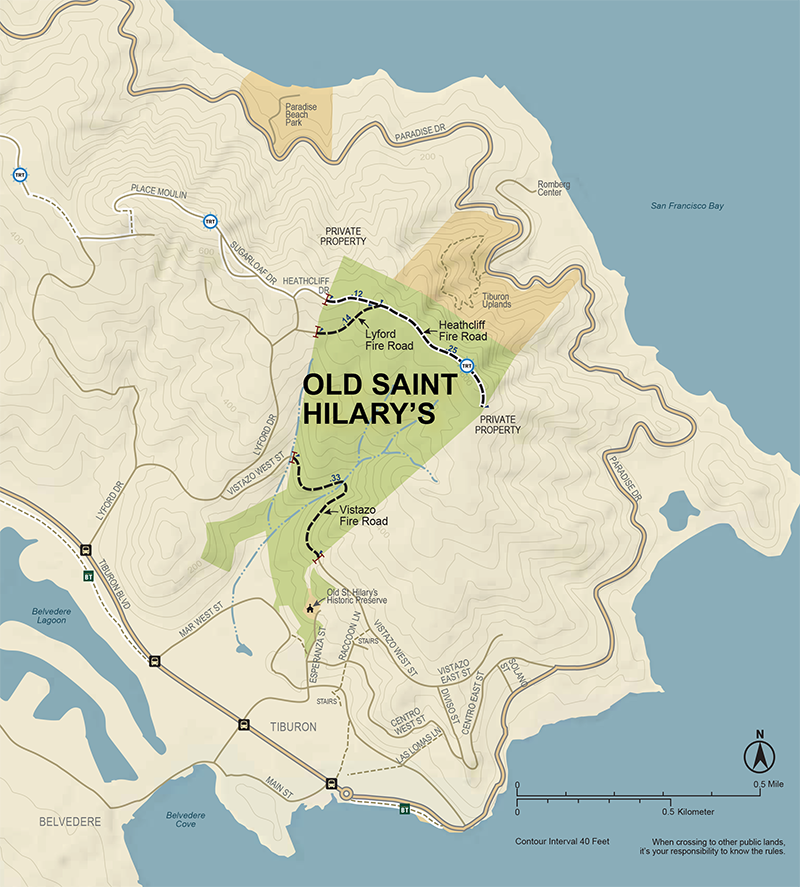

The ferry to Tiburon makes a quick stop at Angel Island, where most people get off. A festive group of international visitors stay on for Tiburon. Watching them take selfies with the views reminds me not to take the Bay Area’s beauty for granted. I leave them behind at Tiburon’s harbor, sleepy on this weekday morning, and trek up to Old St. Hilary’s Church via a trail parallel to Beach Road. Emerging onto Esperanza Road, I am rewarded with my first view of the church, framed by coast live oaks.

Built in 1888 to serve railroad workers in Tiburon and surrounding communities, this charming Carpenter Gothic-style church is now a historic landmark, surrounded by a 122-acre wildflower preserve. Today the church connects visitors to Tiburon’s past, as the end of the railroad from Petaluma, from where enormous ferries transported people (and entire railroad cars) to San Francisco. Signs outside the church, which is open on Sunday afternoons April through October, describe its history and natural setting: serpentine rock covered by grasslands that support a diversity of wildflowers, some endemic to this hillside. I’m here in October, when the garden and hills are dry and brown, but I make a mental note to return for the spring flower display.

The trail behind the church exits the preserve onto residential Lyford Drive, which then re-enters the Preserve at the Lyford Fire Road. Stunning 360-degree views from the top sweep clockwise from San Quentin, up to Napa, and all the way around the East Bay and San Francisco to Belvedere and Sausalito, with the Golden Gate Bridge in the distance. From there, I scramble down a dry creek bed to the Vistazo Fire Road, just above the church, which takes me into residential Vistazo West Street. I discover stairs hidden between houses that take me down to Raccoon Lane, and then back down to Tiburon Boulevard, to catch the ferry back to San Francisco.

Tiburon offers less hilly hikes along Richardson Bay towards Blackie’s Pasture, or following Paradise Drive east from the ferry terminal towards the Railroad Museum and Schooner Cove.

Also a short walk from the ferry, the hilly streets and stairways of Belvedere Island offer fantastic views and house-gazing.

Treasure Island and Yerba Buena Island: What’s under the bridge

The contrasts between flat, human-made Treasure Island and rocky, natural Yerba Buena Island are obvious to anyone gazing across the Bay. From the ferry, I notice both are undergoing massive construction. Cranes and construction barriers dominate the view, leaving me unsure where I can explore.

First, I visit Treasure Island’s most iconic site, Building 1—the Art Deco structure built for the 1939-1940 Golden Gate International Exposition. Treasure Island itself was quickly built by the US Army Corps of Engineers (using 25 million cubic feet of mud) to host the fair and an airport for the Pan American Airways Clippers. But at the start of World War II, the military took over the island. Building 1 now hosts the free, unpretentious Treasure Island Museum, highlighting local history.

A steep road connects Treasure Island to Yerba Buena Island, which peaks at 338 feet above sea level. On my left, a new accessible path leads down to Clipper Cove Beach, a protected recreational area with views of the East Bay and the Bay Bridge. On my right, a new native plant garden winds up the hill to new condominiums. Even late in autumn, blooming sticky monkey-flower, seaside daisy, and yarrow add color to the hazy SF skyline scene. Within only 150 acres, Yerba Buena Island’s landscapes include riparian, tidal, woodland, and grassland areas—an impressive spread of biodiversity.

I meander through the construction until I’m almost directly under the new eastern section of the Bay Bridge. Below lies stately, mostly deserted military housing and the still-active Coast Guard Station. Amongst gnarly old eucalyptus trees, a new native stormwater garden is being planted under the bridge. From the Coast Guard Station, I wander out to the Bimla Rhinehart Vista Point, under the Bay Bridge. Opened in 2019, this hidden picnic and viewing area creatively incorporates remains from the Bay Bridge’s original east span and offers views of the troll who supposedly now lurks under the new span.

Heading back up to Yerba Buena’s top, I check out the entrance to the Bay Bridge East Span Path, the bike and pedestrian path over to Oakland, which is part of the Bay Trail, and make a note to try that another day. A shuttle driver on break between ferry pick-ups offers to take me down the hill to Mersea, a funky Treasure Island restaurant pieced together from shipping containers. After a relaxing beer, I stroll further north along the Bay, then circle back to the ferry. I’ll return to see how the landscape restoration and construction is going, and explore more of these islands.

How to get on a ferry

• Ferry maps and schedules. For East and North Bay, you’ll take the San Francisco Bay Ferry. For Angel Island and Marin, it’s the Golden Gate Ferry. From San Francisco, one-way ticket prices vary from $4.50 (to East Bay destinations) to $9 (to Vallejo). Clipper Card is an easy way to pay and to get youth, senior, low-income, and transfer discounts.

• Bikes can be brought onto ferries for free, if space allows.

• San Francisco Bay Trail maps are available from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.