Luke Ellison is holding something most of us will never get to see: a Delta smelt. Graceful, iridescent, and about as long as my finger, these fish are so rare in the wild that just six adults were found during a sample survey of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta last spring. And the Delta is the only place in the world where this endangered species lives—in the wild, that is.

Delta smelt also live in enormous round outdoor tanks and smaller tanks inside dimly lit trailers filled with the sound of running water. Crowded onto two acres near the edge of the Delta, the neat rows of tanks and trailers comprise the UC Davis Fish Conservation and Culture Laboratory (FCCL), which maintains a captive population of 10,000 smelt as a hedge against their extinction in the wild and another 10,000 for research. If the wild smelt die out, the captives will be released in an effort to keep the species going. Just 50 miles east of Berkeley, the lab, founded in 1996, feels a world away amid cow pastures, vineyards, and orchards.

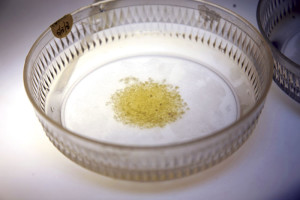

Ellison, the lab manager, deftly squirts eggs from a female smelt into a dry bowl, where they form a tiny yellow mound. Next he adds milt from a male, gently swishing the slender fish around the bottom of the bowl to mix the milky sperm with the eggs. Then he adds water, activating the sperm and completing this act of artificial conception. “We used to let them spawn on their own in the tank but this way we can choose the pairs,” Ellison says. “That lets us make sure they’re genetically diverse.”

Listed as threatened by the federal government in 1993 and as endangered by the state in 2010, Delta smelt were once common. “In the 1970s, they were one of the most abundant fish in the estuary,” says UC Davis biologist Peter Moyle, a leading expert on California’s inland fishes, including Delta smelt. “We caught them by the hundreds in sampling nets.” Those days are long gone, and last summer’s survey for juvenile smelt found only one. Moyle predicts that the species will go extinct in the wild within the next few years.

To prepare for that likelihood and institute a plan B, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation recently extended FCCL’s funding for four more years. The effort is costly at about $2.5 million annually. “We need a lot of power to pump and cool water, and a lot of people to handle the fish,” explains FCCL director Tien-Chieh Hung. And why is the BOR investing so much in this effort? This agency operates the Central Valley Project, which delivers Delta water to Central Valley farms and cities and is therefore one of the main causes of the smelt’s decline.

Another is the State Water Project, which also delivers Delta water to Central Valley farms and Southern California cities, and both projects get water via the Banks Pumping Plant. In what must be unintentional irony, FCCL is a mere two miles north of the pumps that marked the beginning of the end for smelt in the Delta. The pumps, which suck water from the Delta and send it south, also suck in Delta smelt and crush those unfortunate enough to get too close.

While the state installed fish-protecting screens upstream of the pumping plant in 1968, that didn’t change the fact that the pumps divert freshwater flows from the Delta, making the water there too salty and warm for smelt. Drought, of course, does the same thing. Other major threats include invasive fish that eat juvenile smelt, as well as invasive clams that eat the tiny crustaceans called copepods that are the mainstay of the smelt’s diet.

“It’s hard to be optimistic about smelt,” Moyle says. “There isn’t good habitat for them anymore.” Their sensitivity to water quality makes them the aquatic equivalent of a canary in a coal mine—as goes the Delta smelt, so goes the Delta ecosystem. And if the smelt can’t make it, prospects are dim for the Delta’s other at-risk fish, such as green sturgeon, longfin smelt, and winter-run chinook salmon.

Historically found from the point where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers flow into the Delta to Suisun Bay, most Delta smelt spend the majority of their lives in brackish water, where the fresh water from upstream mixes with the salt water from the ocean, but migrate to fresh water to spawn. They live for just one year, so the lab breeds the captive fish annually, in sync with their natural spawning cycle which begins in late January.

The artificial spawning process is a painstaking one. To match up the 300 pairs that researchers believe will ensure the genetic diversity essential to healthy populations, smelt handlers start with a pool of about 2,500 fish. Ellison shows me how to calm smelt in a bath of light anesthetic, inject a minuscule ID tag under their translucent skin, and snip a sliver from their tail fins. The procedure is quick and the smelt barely seem to notice.

Tail fin snips go to the UC Davis Genomic Variation Lab for DNA analysis, revealing who should mate with whom, and the ID tag lets smelt handlers find the fish chosen to parent the next generation among the 2,500 contenders. After spawning each pair by hand, handlers incubate the sticky eggs in transparent columnar tanks, which bathe them in running water that is collected from the Delta and then cleaned and cooled.

As the fish hatch, the water current carries the tiny hatchlings into a raising tank. They are so small that “they look like dots with tails,” Hung says. The hatchlings eat even tinier animal plankton, called rotifers, and just-hatched brine shrimp, both of which are grown on site in barrels of bubbling water. Each year the lab starts the breeding process with about 200,000 eggs in order to end up with 10,000 adult smelt in the captive or “refuge” population.

To boost the refuge population’s genetic diversity, the lab has a permit to collect up to 100 Delta smelt from the wild each year. “We compare the genetics of the wild and refuge fish to make sure we’re not too far off,” Hung says. To assess the lab-bred smelts’ chances of survival in the Delta, he also plans to see if they tolerate salinity and avoid predators as well as the wild ones. Although similar, captive and wild smelt are not genetically identical and may also behave quite differently, so releasing the captives into the Delta—where they could breed with and alter the wild smelt—is a last resort.

Last year FCCL couldn’t find any wild smelt nearby, so instead it collected from the Sacramento River’s deepwater ship channel, which is in the northeast Delta near West Sacramento. Discovered in the 2000s, this population of smelt spend their entire lives in fresh water rather than living in brackish water as adults and returning to fresh water to spawn as those in the rest of the Delta do. And if the day does indeed come when there are no wild smelt to be found, FCCL’s backup smelt will be ready and waiting for us to share the Delta with them once again.