The Bat Brigade waits for the sun to set in Sunol Wilderness Regional Preserve. Pencils, clipboards, and data log sheets in hand, these volunteers stand before a set of wooden boxes—almost flat, like panels, with narrow openings at the bottom—attached to the back of the visitor center. Another group of volunteers sits 20 yards away at another panel mounted to a post like a scoreboard. Across a parking lot and service yard, a third team waits at a larger wall of panels decorated with medieval spires and battlements. David “Doc Quack” Riensche, wildlife biologist for the East Bay Regional Park District, calls this the “bat castle.” The Bat Brigade is his name for the rolling roster of volunteers who help him conduct surveys of bats throughout the East Bay.

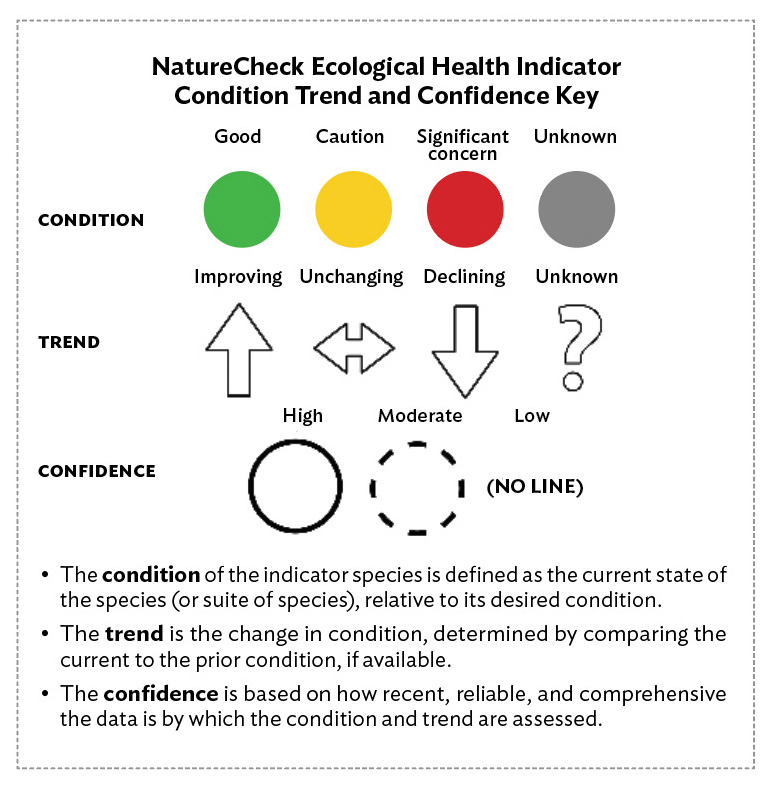

This is a series on NatureCheck, a scientific collaboration looking at indicator species to assess East Bay habitat. You can read the full report here. (Illustration by Jane Kim)

Other STORIES IN THIS SERIES

How Healthy Is the East Bay’s Habitat? An intro to NatureCheck, and how you can help.

Measuring Migration From the Hills to the Sea Rainbow trout depend on healthy streams.

The Wildlife-Rich Grasslands Checking in on ground squirrels, tiger salamanders and golden eagles.

Finally, the sun casts its last glow. Frogs croak from Alameda Creek. Mosquitoes buzz. And then, out of the castle, winged mammals charge from the keep. At first they drop one by one from the narrow openings. Then they begin pouring out like water from a tap, their wings fluttering at imperceptible speeds.

Three species share the artificial roosts and go their separate ways to forage. The Mexican free-tailed bat, named for the tail that sticks free from its tail membrane, flies fast and high, snatching moths from the open air. The small, mouse-like California myotis zooms to the treetops to find insects in the oak woodland canopy. And the Yuma myotis swoops low over the creek, sending out high-pitched vocalizations beyond human hearing to echolocate caddis flies and other bugs above the water.

During his 30-year career with EBRPD, Riensche has been a champion for bats in the East Bay, leading volunteer surveys and educational programs to understand and inform the public about the 16 species of bats reportedly seen in the Bay Area—the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the 1,400 species of bats worldwide. Even in the East Bay, bats are diverse. Some prefer rock outcrops, treetops, and crags, while others roost in bridges and barns. The Piedmont Stables at Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park, for example, host a large colony of big brown bats.

“Bats are amazing,” Riensche says in his typical excitable but matter-of-fact way. “And they are in trouble.” Habitat fragmentation, insecticides, climate change, wind farms, and wildfires are just a few of the stressors bats face. Bats also encounter human persecution, Riensche explains, catalyzed by overblown fears of diseases like rabies and, more recently, coronaviruses.

Much of Riensche’s knowledge of East Bay bats comes from exit surveys—counting bats as they leave their roost to forage—and bat acoustic monitoring software that identifies species by their call, recorded with a high-frequency microphone. As part of NatureCheck, Riensche is standardizing his surveys to follow the multiagency North American Bat Monitoring Program protocols. In 2021, the Bat Brigade, along with agency biologists and park staff, conducted the first year of solstice exit surveys, collecting a baseline of data on East Bay bats. The surveyors are repeating the count this year, while Riensche collects call recordings on a field laptop situated on the bed of his green EBRPD pickup. Together, these two metrics can help track how many bats are roosting during the breeding season, which in turn can provide insight into the health of the ecosystems bats depend on.

East Bay bat species

Pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus)

Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii)

Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus)

Red bat (Lasiurus blossevillii)

Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus)

Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

California myotis (Myotis californicus)

Long-eared myotis (Myotis evotis)

Fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes)

Long-legged myotis (Myotis volans)

Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis)

Canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus)

Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis)

Little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus)—Rare

Small-footed myotis (Myotis ciliolabrum)—Rare

Big free-tailed bat (Nyctinomops macrotis)—Very rare

And as far as bats as an indicator species goes, those ecosystems can be broken down into two components: healthy roosting habitat and insects.

“Bats eat bugs. A lot of bugs,” says Riensche. “A lot, a lot, of bugs.” So many bugs, in fact, that without bats, the North American agricultural industry would lose up to $3.7 billion a year in pest damages, according to a 2011 report in Science. For the future, one of the network’s goals is to better understand the East Bay’s invertebrate populations and diversity. This is especially important now, on the brink of what some scientists call the insect apocalypse. Studies have shown that insect populations are plummeting eight times faster than those of mammals, reptiles, and birds.

But tonight, in Sunol, the bats indicate the insects are buzzing. Once the bats are lost in the dark of night, the Bat Brigade ends its count, packs up, and heads home. In total, they counted 256 individuals. But at his truck bed, Riensche’s laptop still clicks with frequencies. He concentrates on the screen, waiting for a pallid bat or a Townsend’s big-eared bat—both designated as species of special concern in California. He knows pallid bats roost here alongside free-tails and myotis. He’s unsure about Townsend’s. “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack,” he says, but he plans to keep searching.

species Assessment for hoary bat:

East Bay Stewardship Network partners