On a clear day in mid-August David Loeb and I paused on the beach at Point Reyes. “I wonder if that’s serpentine,” I said, as we considered a greenish outcropping jutting up from the dunes. Loeb and I had been hiking at a good clip punctuated with frequent stops to appreciate quail, white-crowned sparrows, and Indian paintbrush. Loeb demurred on the crumbly formation. We were possibly looking at granitic rock, he said, which characterizes much of the Pacific Plate the peninsula sits on. By contrast, “serpentine is associated with the North American plate. Of course the two plates meet right here at Point Reyes,” he added.

Teasing out a geologic mash-up, puzzling over layers of vegetation and small mammal and bird communities, and reflecting on our own human presence in a singularly ravishing place, Loeb and I could have been hammering out the lineup for an issue of Bay Nature magazine. The publication Loeb co-founded 17 years ago and has edited until recently uniquely conveys the pleasures of a recreational hike informed by history, science, and conversation among friends. “You get the whole Bay Area gestalt on this one loop,” Loeb remarked. “It all comes together right here.” The same could be said of his magazine.

We had begun one of Loeb’s favorite walks at the Laguna Trailhead and ambled through coastal scrub to the ocean. Stepping gingerly, we managed not to discomfit a flock of elegant Heermann’s gulls, their orange-tipped beaks showing a bit of finesse among big western gull interlopers. Shorebirds stopping over or taking up residency at Point Reyes have created their own generational loop here for eons, and their theme of eternal return has created as much a sense of wonder as the sight of an uncommon species. With Loeb departing from the daily doings of the magazine, there is a similar sense of moment, its significance created by all that has led up to now in his tenure, and all that will continue to unfold thanks to his vision.

Full Circle

And right here, or very close by, is where David Loeb, a New York City born and bred easterner, fatefully merged his Harvard-schooled history and literature major sensibility with our local flora, fauna, rocks, and water. On a youthful visit to Limantour Beach in the 1970s, Loeb had a revelation worthy of the hippieish milieu. “Obviously,” he told me, “this was the place I was going to live.” He moved west. “I started hiking a lot,” Loeb said. “And wondered, ‘Wow, how was this landscape formed?’ I felt there was something much more powerful going on here than its just being beautiful. But I didn’t have an intellectual construct to really inquire into that.”

After studying film for two years, Loeb joined the People’s Bakery Collective, making bread for collectively-run natural food stores in various San Francisco neighborhoods. His social justice and community-building instincts met up with the publishing world in the late ’80s and early ’90s. “The U.S. was actively destroying a people trying to live just and whole lives,” he told me, referencing the Central American wars in which the U.S. government was trying to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. “That hurt,” he said.

The publications he worked on at the time literally gave voice to the people themselves, particularly those in Guatemala. “Our impetus was to let people tell their stories in their own words, to stop that hurt—to help forge a real connection with people past the politics.” Eventually, Loeb felt he wasn’t effecting enough change.

Ways of Seeing

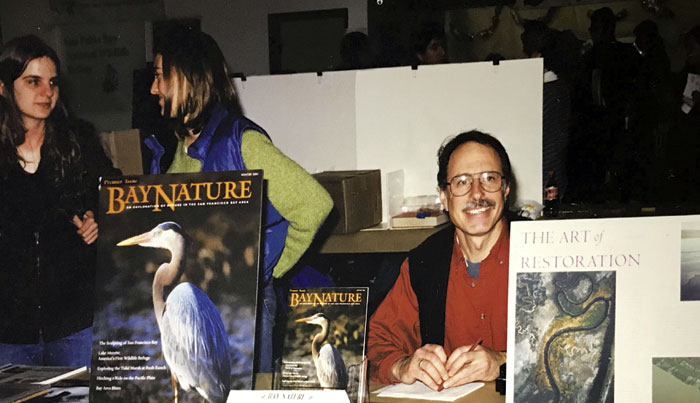

Returning to his nascent desire to understand the what, when, and how of the Bay Area’s natural world, Loeb pondered a local magazine devoted to the subject. He envisioned a vehicle for exploration that would help people develop a deeper bond with their own environment. Partnering with publisher Malcolm Margolin, now legendary emeritus of Heyday Books, he founded the magazine in 2001. From the beginning, Loeb’s concept included a mechanism for helping to protect the very landscapes he extolled. He took the idea of the magazine to scores of local environmental organizations, partly to mitigate any anxiety they might have that it would usurp their memberships. “Their feedback was, ‘This is great. Tell the stories about the lands we’re trying to protect, and we’ll do the campaigns.’ That fit perfectly with what Malcolm and I wanted to do.”

One of Loeb’s favorite stories, looking back over these 17 years, appeared in the October-December 2001 issue, the magazine’s third. “The Dream Given by You: Welcoming the Salmon Back to West Marin” by Jules Evens is indeed iconic of Bay Nature. Evens puts the biotic world within the deep framework of the geology and hydrology of the Lagunitas Creek Watershed, describing the historic weather patterns that developed here “perhaps 8 million years ago,” and says “the earliest settlers were salmon—coho and steelhead—along with salamanders and the redwoods.” The piece layers in personal story with poetry, science, and indigenous lore, gathering the ties that bind us in a seamless whole that is a pleasure to read. “I had plenty of time to work on that story with Jules,” Loeb recalled. “With some updates it remains relevant today.”

It is an amazement to read 17 years of Bay Nature magazine and reflect that the stories it tells so entertainingly have also instructed so well. The regular Bay Nature reader today understands that natural processes unfold across multiple, interconnected scales, and that we humans have a vital role to play in their continuance. Not only does the magazine function as a guide to physical locations and how to visit them, it has also guided how we think about them. While environmentalists have argued passionately for and against the relative merits of pure wilderness and human-impacted nature, the magazine has unobtrusively negotiated a truce between these concepts and provided way-finding for readers curious about both.

Story Maps

Loeb’s leadership of the magazine was interrupted by cancer in 2004; fortuitously Dan Rademacher had just come on board and ran it for about nine months. “David and I overlapped for half a day before he went into chemo at the time,” Rademacher told me. “It was a big deal for me to take on this thing he had started—the relationships, the presence of the magazine in the community, and the way people responded when I called up as the new guy showed how people were trusting the magazine and David. He came back and we really collaborated over the next nine years,” Rademacher told me.

“David was always wanting to go a bit deeper and truer to the values of the scientists and the naturalists we covered,” Rademacher added, emphasizing Loeb’s devotion to quality. “He has a driving curiosity, which he lived out every day in the office and on the trail.” Remarking that when Bay Nature began it was something of a “charity case” for established writers accustomed to getting paid more than the nonprofit could offer. He said Loeb’s steady gaze and caution are the reasons “the magazine is still here all these years on.” Many top-drawer writers have come back again and again to write about subjects they are passionate about.

“If you want to grab eyeballs and imagination, you have to have an extremely good visual quality,” Larry Orman told me. A longtime Bay Nature Institute board member and supporter, Orman founded Greeninfo Network, which, among other visual communication services, makes environmentally focused maps. Maps are a regular feature of the magazine, and Loeb has been a champion of developing them as a part of the story-telling language of conservation. He helped make maps that bridge the worlds of science and lay readers.

All Together Now

And, of course, a magazine, and Bay Nature’s other programs, really hits its mark when it helps create a community. “I love it,” Ellie Cohen told me. The CEO and president of Point Blue Conservation Science, Cohen is herself a maverick in the Bay Area environmental arena, and she was one of the very first recipients of Bay Nature’s Local Hero awards. “I love to read about places I’ve never been to and places I have. Everything about it is top-notch.” Cohen pointed out that the magazine does more than enlighten and entertain—it coheres not only nature, but people across scales.

“Unlike other estuaries, we have 103 municipalities around the Bay Area that are really not unified by anything other than Bay Nature magazine!” Cohen said. “Ecologically we are all interconnected and the boundaries are all human-made. David found a way to bring us together and to understand ourselves as one ecosystem.” Noting that the Bay Area is home to many institutions at the forefront of nature-based solutions and ecosystem science, she added, “The “magazine helps the community come together, to learn from one another. There’s nothing else like it that is Bay Area-wide that can connect the practitioners, the researchers, the policy makers, and the general public. And David deserves a lot of credit for focusing on climate change when others avoided it.”

Back to the Future

Loeb has called climate change “exhibit A” in making the case that a perilous number of people carry out their lives with little or no awareness of our connection to nature. “We do still depend on the natural world and its resources for survival,” he has said, “even if we are separated from that reality by many layers of plastic packaging.” Bay Nature covers climate science in a way that brings highly technical and sometimes abstract-seeming concepts down to earth. It helps readers examine complex technological solutions and how they fit, or don’t, with more traditional nature-loving values. For example, a recent piece by staffer Alison Hawkes pondered the potential use of gene manipulation to control invasive species.

At the same time, Loeb has circled back again and again to stories about traditional life ways, what we can learn from them not only about the past but about making better choices going forward. “I’ve wanted to help create an alternative narrative,” he told me. “To give voice to people, to species, to landscapes we are often moving past without seeing or hearing.” He has reminded us that indigenous people first named the places we now call the Bay Area, embedding those names with stories that pass on important cultural information to subsequent generations. As we are at pains to read and understand that information today, Bay Nature has been and will continue to be an invaluable guide. And so too the man who founded it.

“I’m still going to be hiking and birding and doing all the things I love to do,” Loeb said. “I’m just letting the hard job of putting out a high-quality magazine go to the next generation.”

Loeb had intended to extend our hike down to Sculptured Beach, but once past the gulls we realized the tide was too high to get there. So we trucked up the beach and continued back around on our loop, heading into a verdant tunnel. “Now we get to go back along a riparian corridor,” he said with glee. “An entirely different set of species!” Song sparrows darted in the foreground and Loeb pointed: “A warbler?” Well, perhaps we would find out. We followed on as a flash of yellow disappeared into the green.

Mary Ellen Hannibal is an award-winning environmental journalist and author of Citizen Scientist: Searching for Heroes and Hope in an Age of Extinction.

-300x225.jpg)