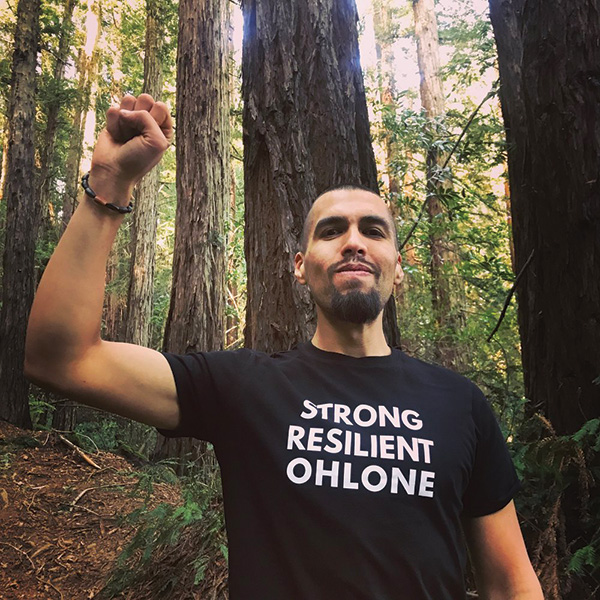

Editor’s Note: An Ohlone cultural revival has taken hold in the Bay Area in recent years. Languages, basket artistry, land stewardship, and ceremonies have been brought back to life, and now, Ohlone food has too. Vincent Medina, a member of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, and Louis Trevino, a Rumsen Ohlone, are rediscovering the ingredients native to Bay Area lands and the favorite dishes of their ancestors. Having prepared their traditional foods (with modern twists) for their communities and the public at events, they are now opening the first cafe dedicated to Ohlone cuisine.

Vincent Medina:

The East Bay is home: the home of my family, my Tribe, and the place where our people have always lived. Long ago, back in the ancient days—our old people teach us—the world began here on the peaks of tuuštak (Mount Diablo) during a great flood that covered Earth with water. Since those beginning times our people have never left this place. I feel proud to know how rooted I am. I grew up in San Leandro and San Lorenzo, close to the same creeks where my ancestors fished salmon and steelhead. It’s the same place where many of our old villages were before contact with outsiders. It’s where most of us still live today. It’s where I’m from.

I come from an old East Bay family. My great-grandmother, Mary Archuleta, was proud of her Indian identity and instilled that pride in all of my family. Growing up, I remember elders who, like my great-grandma, carried themselves with a quiet dignity. These people knew who they were. That generation did everything they could to keep our identity alive.

When I was a young person, my family and my Tribe strengthened our bonds to Ohlone culture; my parents drove me up dusty roads to Sunol for tribal camp, and we spent time in the tule marshes at Coyote Hills. Being in these landscapes with older Indian people gave me an understanding of how deep and layered our story is here. Not everything could be passed down to us, however, and it hurt to learn the reasons why.

European colonizers first arrived in the East Bay in the late 1700s. Spain, Mexico, and the United States claimed our homeland at different times. Each actively worked to erase us from the land. They suppressed every aspect of our Ohlone culture—from our Chochenyo language to our basketry, from our religion to our cuisine, to our very names. Laws impeded our people from keeping their practices alive under the Spanish. The Mexican Californio caste system didn’t allow Indians to return to the land. And California’s American government offered bounties for Indian scalps during the Gold Rush.

Despite these difficulties, our ancestors persevered. They kept information about the traditional ways alive. One way was with recordings. In the 1920s and ’30s, old-timers living in Niles and on the Pleasanton rancheria, where my great-grandma was born, shared the old ways with linguists and anthropologists from Washington, D.C. Tribal elders Angela de los Colos, Jose Guzman, and Susana Nichols recounted everything they remembered about our language, stories, religion, dances, the land we come from, the food we ate, and much more. They also described the injustice our people experienced. These recordings are what makes revival of the old ways possible today.

When I read about my culture in those old handwritten documents, it brings up powerful feelings. I’m compelled to do something, to work to restore the things that were taken from them—and from all of us. I’ve studied those notes for the past seven years and peered deeply into the practices of my people. I have learned Chochenyo, the language of my ancestors. I now speak it with conversational fluency with others in my family, and this gives me hope for what is possible.

In those old notes, our people often talked about food. I associated typical Indian foods with things like fry bread and buffalo, but these elders mentioned chia, venison, gooseberries, acorn, clover, and manzanita. They shared how our ancestors preferred traditional Indian foods over introduced foods. They almost always pair the names of each food with a translation in our language. Many foods are associated with a story, some of those stories even stretching back into our Creation times.

Everything I read made me want to try these foods. So in 2016, my Rumsen Ohlone partner Louis Trevino and I began locating places in the East Bay and Carmel Valley where our traditional foods grow. We started gathering plants like Native teas, learning how to give gratitude, to pray over the plants in our languages, to take only what we need. And then we fell in love with these foods—the rich, if subtle, flavors that come from the land we come from; the dark blackberry purples, deep acorn brown, and muted watercress-green colors; the scents of pine and bay laurel and minty yerba buena; the way the food makes us feel. Louis and I are focused on making sure Ohlone foods are part of the larger revival in our community.

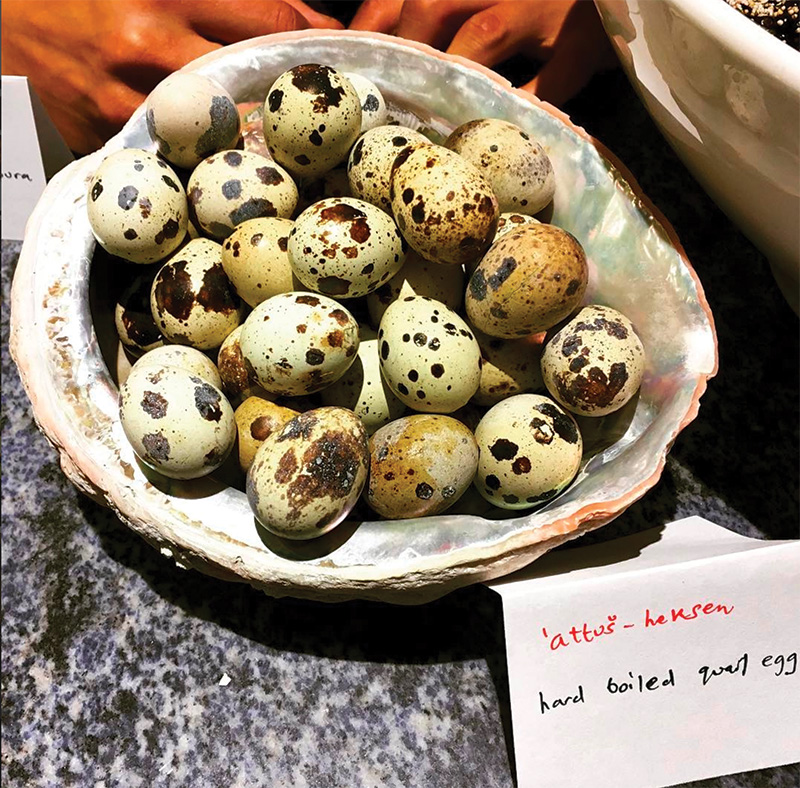

In September 2017, we launched mak-‘amham, which in Chochenyo means “our food.” mak-‘amham is a “guerrilla restaurant,” meaning that we move around our homelands serving our Ohlone cuisine. To share this work, we host gathering trips, cooking classes, and formal dinners for Ohlone people, so they have the tools to keep these culinary customs alive and pass them down to their own families. We hope that acorn soup will become a comfort food again, and that quail eggs will one day be more popular among our people than chicken eggs. We believe these foods can improve the collective health of our communities by providing a nutrient-rich, traditional diet.

mak-‘amham also creates physical spaces where our people can see Ohlone culture reflected outside of their homes, a place where the public can learn about our culture and our cuisine. We are opening Cafe Ohlone by mak-‘amham in the back of University Press Books in Berkeley. Our cafe operates three days a week, and we offer seasonal small bites, such as acorn bread, soft-boiled quail eggs, pinole seed cakes, and bay nut truffles, alongside smoked traditional meats wrapped in local herbs and four different locally gathered Native teas.

I am proud to see our culture return home. Our ancestors and elders left us with the knowledge to keep our story alive. The revival of our language and food traditions rights an historical wrong. In Chochenyo language, the oldest language of the inner East Bay, we say holše mak-nuunu— “our story is beautiful.” muyye mak-muwekma—“our people are strong.” ‘ayye makiš haššemak horše mak-muwekma hemmen tuuxi—“and we do right for our people every day.”

Louis Trevino:

Food, for me, has always been inextricably tied to family, to security and warmth, to culture, and to love. As a child, I spent a great deal of time in the restaurant opened by my great-grandparents Jim and Connie Cerda, El Rancho Grande. While I never got to meet my great-grandmother Connie, I was intimately acquainted with her sauces, salsas, and more; her recipes made the restaurant a mainstay in their community.

When the restaurant first opened, my great-grandparents lived in the second story of the same building, so that she could begin making her sauces before sunrise. Through her recipes—the herbs, spices, produce, and meats, and the long and slow cooking methods—I got to know my great-grandmother. I always felt secure in the restaurant, surrounded by family and love. It was there I learned to count change, swim, and even ride a horse. It was also there, with my grandmother Marylou Yamas, that I learned much of our family’s history. Her stories tell of togetherness and persistence, all made possible by love. She taught me that we are Indian people.

It was there that, at the age of 11 or 12, I first came to know something of our Rumsen Ohlone language. I was given a thin black notebook, with lists of vocabulary words from across Central California. My grandmother told me to pay special attention to the column labeled “Monterey,” because “that is us, that’s our language.” The notebook was a printed copy of Alfred Kroeber’s 1910 publication The Chumash and Costanoan Languages. I pored over those six pages of vocabulary and a telling of the origin of our world. The vocabulary gave a glimpse of the complexity of our Rumsen language. The stories told of our creation and how maččan (Coyote) gave instructions for living and eating well. It was like peering through a tiny pinhole at our Rumsen Ohlone people from before, and I was left with a deep respect for our old world, and a deep sense of wonder at what it must have contained.

For years I thought that this list and these stories were all that remained of our old world. But in 2014, I attended the Breath of Life workshop in Berkeley, organized by the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival. At this conference I met my partner, Vincent Medina, and I first came to know the true depth and breadth of documentation that exists of our Rumsen Ohlone language. Vincent, who is on the Advocates’ board of directors, had already made great strides in the revitalization of his Chochenyo Ohlone language. His progress was an inspiring example of what is possible even when working entirely from documentation. During the conference, I also met Linda Yamane, a Rumsen Ohlone master basket weaver and now dear friend, who had for many years researched our culture. She introduced me to a trove of documentation of our Rumsen language.

The last known fluent speaker of Rumsen, Isabel Meadows, spent the final decade of her life being recorded by an ethnographer from the Smithsonian Institution named John P. Harrington. She spent the last five years of her life traveling with Harrington to Washington, D.C., working closely with him to record what she remembered of our language, history, foods, religion, stories, songs, and more. Harrington also recorded other Rumsen speakers, including Laura and Alefonso Ramirez, Tomas Torres, and others. Faced with the enormity of this documentation, I realized that I had more than just the pinhole to peer through. I could delve into these recorded memories of these Rumsen elders and learn about our culture, language, foods, stories, and songs. I understood then that researching and practicing our cultural specifics would be a lifelong task, and I dedicated myself to it wholeheartedly.

Vincent and I share a deep desire to see our cultures fully revitalized. Our home is a space where our languages, our aesthetics, our songs, our foods, all those old ways are elevated. By immersing ourselves in this documentation, we gain a sense of the perspectives of our people from before on many things, from the injustices they faced to their hopes for the future of our people. We learn about ourselves in the process. We grow to love and care for those people from before and feel they are close to us. We care for what they cared for.

We began some time ago to notice references to foods; pinole and acorn preparation methods; greens and their value for wellness; the pursuit of mushrooms after the rain and berries in the summer. Some of these references talk about specific people and the ways they prepared food differently. And some of these references, as with pullum (acorn bread) and kurkx (pinole), end with an expressed desire to try the food again, because it is so delicious. When those mentions appear, we are filled with a desire to feed these elders the foods that they crave and remember with fondness. By preparing these Ohlone foods today, and celebrating them with our people, we hope to somehow satiate those people from before, to let them know that today we still care for the foods they cared about, and that this way of living continues. To that end, together we launched mak-‘amham, an effort to revitalize our foods as part of the broader cultural revitalization effort. Our Cafe Ohlone by mak-‘amham, much like my great-grandparents’ restaurant, will be a space where our people can feel the security, warmth, and togetherness of our living and thriving culture, and where our young people will be inspired to carry these practices into the future.

All of the work that Vincent and I do is rooted in the love we have for each other, for our people from before, our people today, and our people to come. This is the way maččan instructed the people to eat and live, and this is the way it ought to be.