It’s not surprising that Robert Doyle had his first gardening job at around age 14 or 15. Raised in Concord, before the walnut orchards and wheat fields had given way to suburban developments, Doyle spent his childhood exploring the hills and creeks around Mount Diablo. “I was kinda the cartoon picture of frogs in my pockets and mud in my shoes—or barefoot,” he says. Having grown up on a farm, his mother loved nature and welcomed any critter he brought home, be it a frog, a snake, or whatever else young Bob could catch.

By the time he started high school in the late ‘60s, Doyle had become a bit of a trouble-maker. But after a biology teacher introduced him to Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold, Doyle delved into the history and science of ecology, finding a way to redirect his rebellious energy into something worthwhile, which, he says, “pretty much changed my life.”

By 1970 he was helping organize his school’s inaugural Earth Day. It was a busy and exciting time to get involved with conservation, he says, as environmentalists scored local and national victories, from the grassroots Save the Bay campaign to the passage of the National Environmental Protection Act. Though he was just one of many engaged and energetic young environmentalists, a handful of local leaders saw something special in Doyle.

One of Doyle’s teachers introduced him to those who would go on to found Save Mount Diablo, including esteemed botanist Mary Bowerman, who invited him to join them on surveys around Mount Diablo to look at land that might be preserved. Doyle hiked through places like Black Diamond Mines where he watched, listened, and learned about conservation first hand.

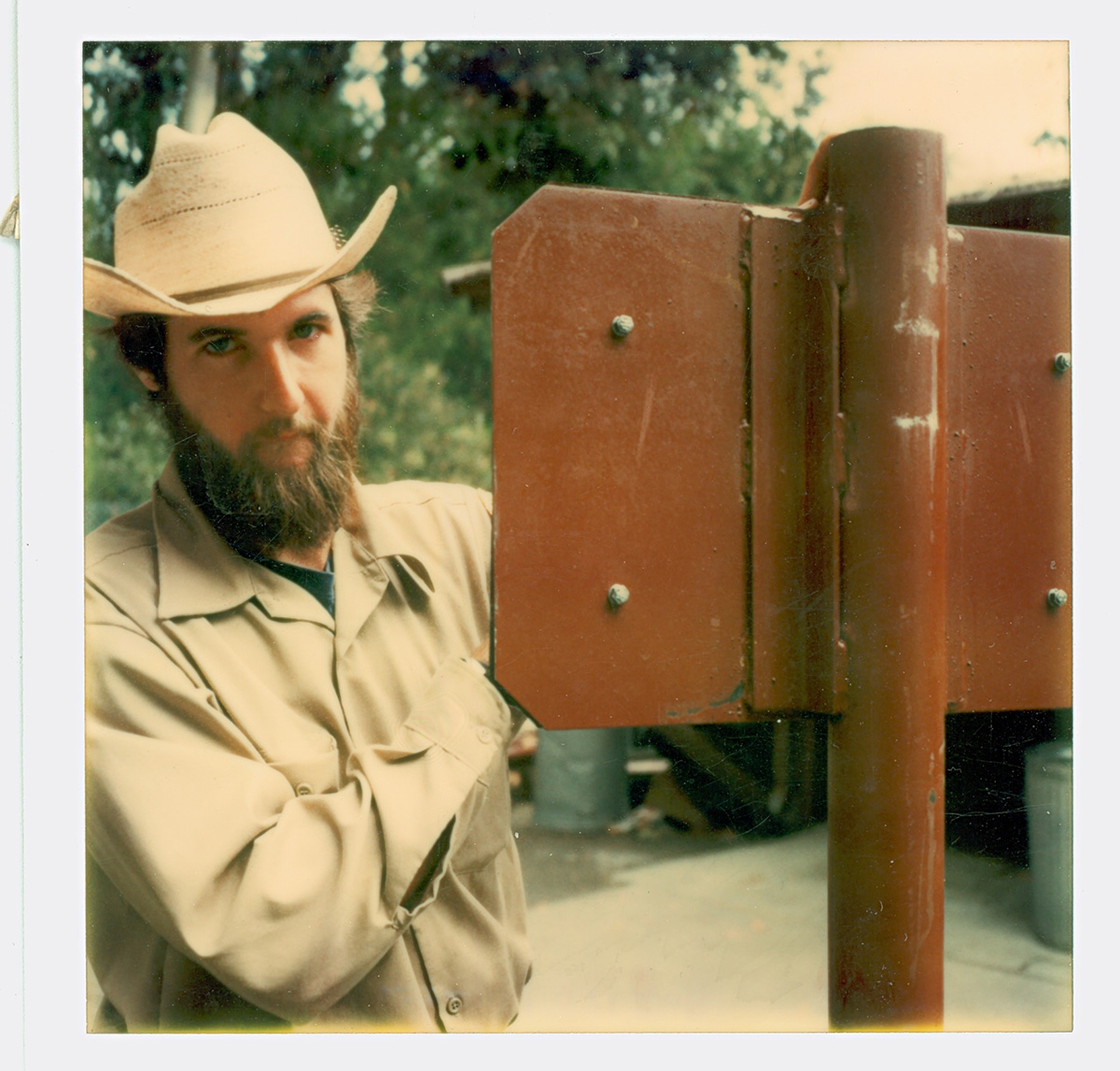

As an eager but unproven young activist, Doyle had access to some of the most influential Bay Area conservation leaders of the day—the “Wizards,” as he fondly calls them. He became a founding board member of Save Mount Diablo, and was advocating for the mountain’s conservation at the state capital by age 19. “I was a young protege, and they really pushed me to do things because I had lots of energy,” Doyle says. Apparently, all he needed was that push.

Doyle was hired by the East Bay Regional Park District as a seasonal ranger in 1973, when the district consisted of around 24 parks on less than 25,000 acres. By the end of 2020, when he retires as general manager, the district will stand at an impressive 125,000 acres in 73 parks—due in no small part to Doyle’s efforts.

During his tenure at the largest regional park district in the nation, Doyle’s gone from having a front row seat to the regional conservation movement to being one of its key players. Through the ‘80s, ‘90s, and ‘00s, Doyle worked tirelessly to save “the best of the last” East Bay landscapes and habitats from urban sprawl and development. In total he’s helped conserve 61,000 acres, open 18 new parks, and develop countless miles of trails.

The park district’s priorities today, however, have changed a bit since Doyle started his career almost five decades ago. The population that the EBRPD serves has increased by 57 percent since 1970, with more racial and cultural diversity. Meanwhile, climate change, which wasn’t on the radar in Doyle’s early career, is contributing to increasingly large and frequent wildfires in upland parks as well as rising tides at the shorelines.

Doyle is proud of all that he’s accomplished—“more than I ever expected”—and says he has no regrets. And yet, when looking to the future, he’s the first one to say, “we need to do more.” In what seems like the end of an era, Doyle is stepping down at the close of 2020 to make way for the next generation of conservation leaders at the district.

Early Years

After a few years as an EBRPD ranger and a brief stint working on responses to environmental impact reports, Doyle got the opportunity that kickstarted his park district career. In 1979, district Chief of Land Acquisition Hulet Hornbeck, who knew Doyle from those hikes with Save Mount Diablo, tapped him to design and develop the EBRPD’s new, interconnected trail system.

Charged with planning the trail routes as well as negotiating with sometimes antagonistic landowners for the rights to build them, Doyle was developing the skills that would serve him throughout his career. “That’s where I learned about land,” he says. “I had to look at who owned what, how to weave the trails through these beautiful places.” By the time Hornbeck retired in 1985, they had completed almost 100 miles of regional trails. “It was a challenging time, but Hulet kept pushing me, and I kept being competitive and it’s a remarkable system,” says Doyle. “I think it actually is the best urban trail system in the United States.”

Doyle succeeded Hornbeck as the Chief of Land Acquisition and Trail Planning—only the second one in the history of the park district. Doyle was in the position for just three years before he was tasked with the huge responsibility of co-authoring Measure AA, an ambitious $225 million bond measure, to help the EBRPD avoid a financial crisis. Over half of the bond measure’s revenue was allocated for EBRPD land acquisition, so it was Doyle who led the effort to determine which lands should be prioritized and how much they would cost. Doyle often likens the passage of Measure AA, and the influx of cash it provided, to “being strapped to a rocket ship and somebody lights the fuse.” Doyle and his team had promised to create 7,500 acres of new parks and expand existing parks by 20,000 acres. Now, they had to deliver.

Expanding the Park District

The years after the passage of Measure AA “was a pretty amazing time to be working at the park district,” says Andrea Mackenzie. Back in the early ‘90s, Mackenzie joined the EBRPD as an environmental planner in Doyle’s department, and now, as the general manager of Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority, she counts Doyle as a colleague and a friend. “A lot of his success and who he’s become was formulated in the ‘90s during this period of great expansion.”

Over the next 25 years, Doyle more than made good on his Measure AA promise. As Chief of Land Acquisition, and later as Assistant General Manager for Land and Planning, Doyle oversaw the addition of more than 47,000 acres to the park district—the greatest expansion of parks and trails in the district’s 85-year history. He added thousands of acres to existing parks such as Morgan Territory and Pleasanton Ridge, bought the land for parks like Bay Point Regional Shoreline and Crockett Hills Regional Park, and added countless miles of trails to networks including the San Francisco Bay Trail and Bay Area Ridge Trail. Altogether, they serve millions of people every year.

It’s easy to look at these parks today and think that their conservation was inevitable. But the victories were hard-won. “Everybody already knows my reputation as being a tough negotiator,” Doyle says. “[I’m] pretty aggressive about implementing the District’s mission.” As a leader, Doyle was tenacious, and he expected the same from his staff. “Bob Doyle was not always the easiest boss to work for,” says Mackenzie. “He challenged us to work really hard, try new things, and learn from our mistakes.” She recalls that Doyle would send her to late night public meetings to advocate for parks and open space, where she met strong opposition from developers. “He’d expect me to go in there and have those hard conversations… He wasn’t afraid to get into healthy debates or even file lawsuits to win the day.”

Doyle has described land conservation as a “competitive sport.” And as the son of an athlete and coach, Doyle has a natural talent for it. “Bob is not a shy soul,” Mackenzie says. “He knows who to talk to, how to get right to the point.” In brokering land deals, he’d leverage the influence of the EBRPD and what they could bring to the table. Both Mackenzie and Annie Burke, executive director of TOGETHER Bay Area, emphasize Doyle’s skill in cultivating partnerships between agencies, nonprofits, and community organizations and developing those regional connections to more effectively conserve parks and open space. In his work to protect and restore McLaughlin Eastshore State Park, says Mackenzie, Doyle “in many ways perfected the partnership between local and regional districts and state parks to work together to get things done.”

Perhaps as a counterweight to his intensity as a leader, Doyle says he likes to make a lot of bad jokes. “You have to laugh because you’re dealing with a lot of tough issues… You try to lighten things up.” He follows up on projects regularly to keep people focused, encouraging them to do their best for the public. “You have a long line of spinning plates and one starts wobbling and you have to run back to that beginning and spin it again,” he says. Most of all, he tries to remind people that he has their back. “And if I have their back… I can push them!” he adds. “See? Another joke.”

General Manager

Park visitors directly benefit from Doyle’s land acquisition work when they use East Bay parks and trails. But much of Doyle’s work has been more behind-the-scenes. The role of general manager, which he stepped into ten years ago, he says, is about funding and people. In addition to managing the system’s staff, budget, and long-term priorities, Doyle advocates for park funding and legislation on a local, state, and national level. Some recent victories include the passage of California Prop 68, the Parks, Environment, and Water Bond, in 2018 and the permanent funding of the Land and Water Conservation Fund with this year’s passage of the Great American Outdoors Act. Mackenzie says Doyle has been successful at influencing public policy because he engages directly with agencies and elected officials. “They say imitation is the highest form of flattery,” she says. “I’ve imitated much of what I’ve learned from Bob in passing funding measures.”

What he’s realized in this past decade, though, is “it’s no longer about you and your achievement. It’s not about ‘you’ve got this many acres preserved, you opened this amount of parks or trails.’ It becomes about you being the mentor and supporter of the people who work for you.” Doyle, probably more than most, understands the importance of having mentors who believe in you, push you, and give you opportunities.

Much of his work as general manager has been about growing the staff, including hiring lots of young people and giving them the tools to be successful. Just as his mentors helped spark his career in conservation, Doyle hopes he’s inspired young people who want to follow a similar path: “What’s kept me going these last years is seeing those bright young minds, and talent, want to learn, want to achieve, and want to work for the public.”

As Doyle speaks about young people, it is hard to ignore that he is referring to my generation. I’m 25—somewhere between a Millennial and Gen Z-er. Doyle says that in the ‘70s, lots of young people were very active and engaged on environmental issues. The same is true today, but what’s changed is the way we organize and the issues that are most important to us.

Doyle, I think correctly, observes that “It’s the younger generation who’s saying ‘that’s great that you bought all this land and that’s great that you did all these great things—it’s not good enough.’” And, ever-ambitious, he recognizes the need to do more. His advice: “Don’t be a complainer…we need to take action.”

But it’s the role of young people to both criticize and take action. Right now, we’re listening and learning from those in power—those like Doyle. We criticize to push the movement to address our priorities, from environmental justice to climate change. Joe Biden has the most ambitious environmental platform of any president to a major political party, and that’s because environmentalists and progressives, especially young activists, pushed him to adopt one.

Perhaps Doyle doesn’t see our activism because so much of it happens online. Doyle tells me that he wonders how the environmental movement will organize around the all-encompassing threat of climate change. In the 1970s, environmental activism was oriented around membership-based groups like the Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, and Save the Bay. Organizations remain a useful tool for organizing and community-building, but digital media is arguably just as important. Some people may scoff at internet activism, but it’s an efficient, accessible, and scalable way to raise awareness and organize around issues.

Thanks to decades of environmental justice activism, climate change and other environmental issues have taken on new political relevance as mainstream social justice issues. If the work of youth-led organizations like Sunrise Movement and 350.org is any indication, the future of the environmental movement is one that centers climate change, racial justice, and economic inequality. Doyle says he believes that the intelligence, skills, passion, and diverse perspectives of young people will save the planet. He’s right.

The Future

Indeed, he’s optimistic about the next generation working toward creative solutions (“like we did in the 70s”) to address two main challenges facing the district: climate change and making parks more accessible to communities of color.

Under Doyle’s leadership, the EBRPD has made a strong start in that regard. Funds from Measure FF, which passed with more than 85 percent of the vote in 2018, are going to forest management and wildfire protection in the hills, as well as restoration and upgrades to shoreline parks, which serve park-poor areas in the flatlands. They’ve also helped launch an innovative Parks Prescription program, which emphasizes the importance of park access as a public health issue.

Regarding climate change, he says, “We’re seeing the impacts on our shorelines with bigger storms, bigger tides, we’re seeing our forests go up in smoke. And I think the East Bay Regional Park District has been a leader in managing the fuels after the ‘91 fire in the Oakland hills, but this needs to be a national, state, and local effort, big time.” Doyle says we need a “climate army” to mitigate the effects of climate change and to do the physical work of land stewardship.

He also sees jobs as the solution to making parks more accessible and relevant to communities of color. He was a founding board member of East Bay Conservation Corps (now Civicorps) which provides young people with education and job training, and he says he’s seen time and time again how offering pathways to fulfilling careers in outdoor recreation makes people, and their communities, feel invited to parks. “Just walk around a regional park, it is extremely diverse… What we have to do is get more of those people working in the parks, and we will.”

The idea reflects a core tenet of the Green New Deal, which bills job creation as a key tool and benefit of transitioning to a green economy. But in 2019, only 34 percent of the EBRPD’s staff were people of color, with very few among senior leadership. Indeed, the EBRPD has never hired a person of color for the general manager position and may face pressure to finally do so when choosing Doyle’s successor.

Burke says, “I think we need to respect the people who came before us,” and the conservation leaders who have “gone the extra mile” to make the Bay Area look the way it does today. “We also need to approach the work differently. Not out of disrespect, but the work of the twenty-first century is more nuanced [than it once was]. It’s not binary—saved or not saved—and I think it takes a more diverse coalition of people to do it well.”

Most regional park visitors have never heard of Robert Doyle. They don’t know that he thoughtfully designed the trail they’re biking down. They don’t know that he negotiated the deal to buy the park land they’re picnicking in. They don’t know that his lobbying won the park district the funding for the open space where they saw a great horned owl, or a California newt, or a river otter.

Those of us who know the history of the EBRPD will remember and honor Doyle for this legacy of conserving the East Bay’s open spaces and habitats for future generations to know and love. But we would do well to remember not only what Doyle did, but how he did it. Doyle’s mentors, the Wizards, believed that with passion, hard work, and perseverance, success was possible. They didn’t consider failure as an option. Doyle adopted this attitude throughout his career. The next generation will do things differently, have different priorities, and take the park district in new directions. But passion, hard work, perseverance, and optimism? Those keys to success are evergreen.