One early summer morning in 2018, Jon Holcomb steered his fishing boat out of Noyo Harbor, just south of Fort Bragg, and headed toward Caspar Point, a jagged promontory along the rocky Mendocino coast. There, he anchored in about 20 feet of water. Yards away, waves roared.

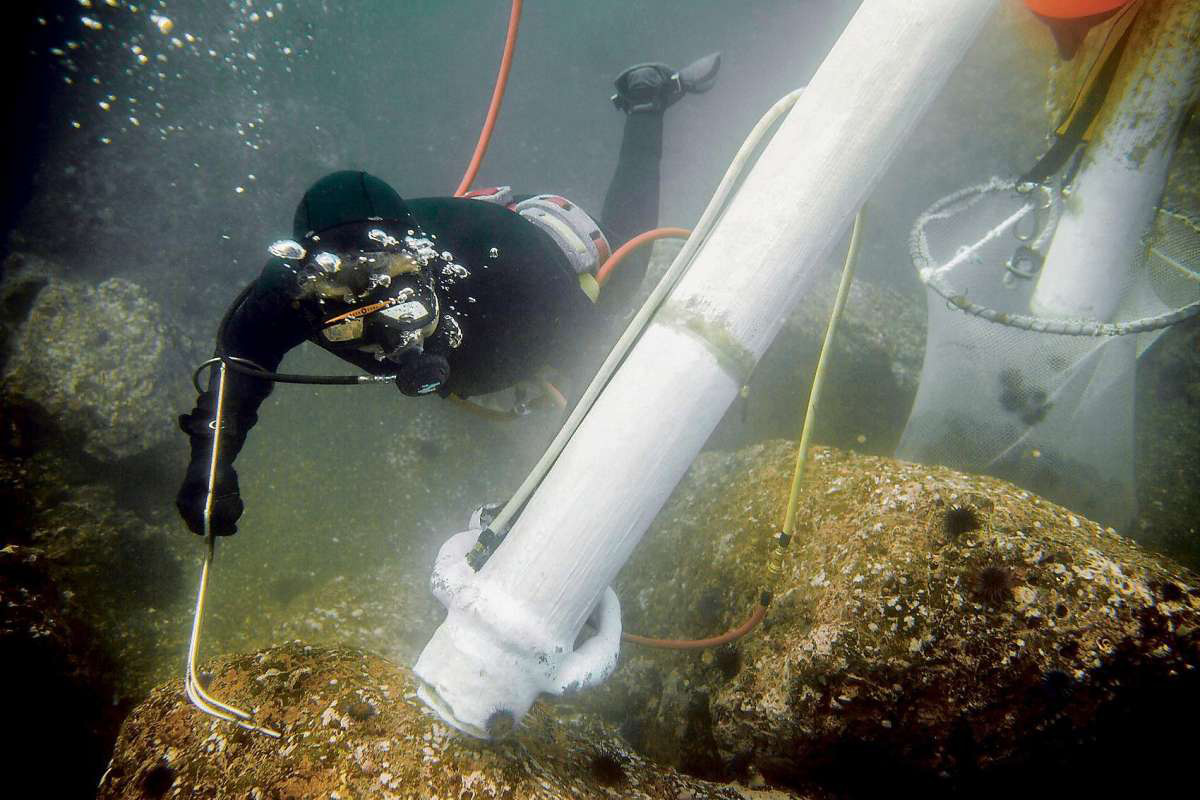

A longtime commercial sea urchin fisherman, Holcomb stayed up top, minding the boat, while his friend and fellow diver, Harry Barnard, submerged himself in the slate-blue water. Under the waves, rock outcroppings covered in spiked purple orbs looked like coronavirus-infected human cells. Other than Barnard and those quarter-size echinoderms, the ocean bottom appeared lifeless. Holcomb and Barnard were there to vacuum up the urchins with a large plastic tube Holcomb had built, called an air lift. In a video taken of the work, Barnard used a long hook to flick urchins off of the rocks and into the mouth of the air lift, where they were sucked into a 350-pound bag.

With visibility at 25 feet, Holcomb says, Barnard was probably looking at around 40,000 urchins. When Holcomb first started working with his air lift, that was about all he could manage in a day. But 40 modifications and 50 dives later, he has gotten that number up to 1,200 pounds, or almost 200,000 urchins. A million urchins every week. The California Ocean Protection Council, a state government body, awarded Holcomb and other urchin fishermen a grant of almost $500,000 to ramp up removal efforts this summer along the Sonoma and Mendocino coasts. “For all my years of diving, I’ve been a hunter-gatherer,” Holcomb says today. “But this is not hunting and gathering anymore. This is maintenance. Kelp maintenance.”

Since 2014, more than 90 percent of the bull kelp along a 200-mile stretch of California’s North Coast has disappeared. The problem isn’t specific to California—globally, kelp forests are disappearing four times faster than rain forests. Kelp forests perform various environmental functions—they’re an important breeding ground and nursery for fish and, despite their equaling less than 1 percent of the plant biomass found on land, they sequester almost as much carbon as terrestrial plants.

While the genesis of the kelp forest disappearance is complex, most everyone concerned with kelp’s recovery agrees the purple urchins, which have stripped the seafloor of every last blade, creating what are called “urchin barrens,” have to go. But how best to get rid of them is a delicate question. Vacuuming them up or removing them by hand is one approach. Another is to let nature take its course and see if the urchins will die out on their own. There are also efforts to reintroduce predators—sea stars and sea otters—that could prey on the urchins.

This divergence in approaches—and their implications for the future health of kelp forests—raises a complicated question: What, exactly, are we trying to restore?

Any attempt to bring back a kelp forest has to begin with a postmortem on a particular forest’s decline. Mark Carr, a UC Santa Cruz biologist known for his expertise on kelp forest ecology, says, “We have to ask, ‘What got us into this situation in the first place?’”

In the case of kelp’s decline along the Northern California coast, the drivers are thought to be twofold. In the summer of 2013, researchers with the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), a research consortium, noticed sea stars in tidal pools along the coast of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula seemed to be “wasting” away, their arms separating from their bodies and decaying into mush. Over the next few months, divers and fishermen from British Columbia to Baja California reported mass die-offs of sea stars, to date having affected more than 20 species and thought to be caused by a virus or several viruses. One of the hardest hit was the sunflower sea star, Pycnopodia helianthoides, which is now locally extinct. Dark purple or burnt orange, with up to 24 arms, the sunflower is the largest and fastest sea star in the world. It’s also now thought to be a top sea urchin predator.

The effect of sea stars on sea urchins can be explained in two ways. The first is straightforward—they eat them. As the sea stars disappeared, urchin populations skyrocketed. The second is a bit more complex. When a sunflower sea star eats an urchin, it crushes the creature’s “test”—the biological term for its calcium carbonate exoskeleton—releasing internal fluids and bits of gonad into the current. Other urchins, sensing this fluid, slink away into cracks and crevices. In a healthy kelp forest, urchins hang out in their hiding spots, avoiding predators and eating bits of kelp that drift by.

Kelp forests rely on the constant upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water to grow as well as to circulate the bits of kelp. But around the time sea stars off North America’s western coast started winding up dead, a large mass of relatively warm ocean water forming in the Gulf of Alaska began to spread south. Scientists in Washington state named this marine heat wave the “blob,” and like sea star wasting syndrome, within a year, it affected the entire western coastline of North America. The “blob” prevented cold, nutrient-rich water from reaching the coast, and kelp stopped growing.

Without a regular supply of kelp detritus settling into cracks and crevices, the urchins grew hungry. And without sea stars, they grew bold. They spread throughout the seafloor, devouring kelp until all that was left was a coral-like algae growing in rigid pink tufts. In areas where sea urchins have stripped away the kelp, the seafloor looks like a giant Pepto-Bismol pink shag carpet. This coralline algae emitted a chemical that has attracted even more urchins, which consumed even more kelp and left behind even more pink fuzz, until the kelp forests had undergone what ecologists call “shift in alternative stable states.”

The kelp forests became urchin barrens, and those barrens will persist until, somehow, the urchins are removed.

The Watermen’s Alliance, a coalition of spearfishing clubs with names like the Long Beach Neptunes and Monterey Tritons, formed in 2008 to fight the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs)—the 120 underwater reserves along the California coast where fishing is severely restricted. Motivated by this mission, the alliance operated as any hunting club might. It organized spearfishing tournaments; petitioned to catch game fish, such as tuna and sea bass, inside the MPAs; and sold a yearly swimsuit calendar (the models wore bikinis made of abalone shells). But as urchins decimated Northern California’s kelp forests, red abalone, which rely on kelp for food, began to disappear. In 2017, the California Fish and Game Commission closed the $44 million recreational abalone fishery due to “ongoing extreme environmental conditions.”

Almost overnight hundreds of abalone divers were stranded on land, and the alliance’s mission changed. “You had all this pent-up energy,” says Francesca Koe, a longtime abalone diver. “People wanted to do something.” The Watermen’s Alliance channeled that energy into killing massive amounts of urchins—so far, it has removed over 60 tons and raised $130,000 to pay commercial fishermen, like Holcomb, to clear coves. The urchin removals were organized, Holcomb tells me, in an effort “to make sure these classic shell fisheries don’t go away, as so many other resources have.”

In the spring of 2019, a coalition of federal and state wildlife agencies, environmental nonprofits, tribes, and fishermen released a plan for restoring kelp forests along the Sonoma and Mendocino coasts. The plan gave commercial urchin removal top-tier status. “It’s like throwing a bucket on a 12-alarm fire,” admits Koe, who co-chaired the working group that drafted the bull kelp recovery plan. “But, quite frankly, doing anything is better than doing nothing.”

Joshua Russo, president of the Watermen’s Alliance, succeeded in early 2020 in pressuring the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to approve a controversial pilot program that will let divers working in Caspar Cove, just south of Caspar Point, smash urchins rather than haul them out of the ocean. “This year, my goal is to get as many divers out there as often as possible,” Russo said, speaking at the Deep Ocean Exploration and Research (DOER) Marine facility in Alameda last February. “It’s all hands on deck.”

Despite all this effort, it’s unclear whether small-scale urchin harvesting can work. “One of the problems that they have with these urchin removal efforts is that the urchins just storm right back in not long after they cleared them,” says Carr, the UC Santa Cruz biologist. “They’re recolonizing those areas so quickly that the forest can’t reestablish.”

Perhaps more important, the coves the divers are trying to clear—such as Ocean Cove, on the Sonoma Coast, and Van Damme Beach, just south of Mendocino—were chosen for their safe beach access and nearby campgrounds, not because they are biodiversity hot spots. “Urchin culling has been a little haphazard in the past,” says Mary Gleason, director of marine science for the Nature Conservancy. “There’s a lot of energy and movement toward smashing urchins, which is great, but we need to be more strategic and focused in where we do that.”

Even as fishermen and divers immersed themselves in urchin removal, scientists watching kelp decline in real time were hesitant to consider restoration. In the past, problems like this went away naturally, Carr says; either a disease would wipe out the urchins, a predator would come in, or a big storm would sweep them off the reef and kelp forests would come back on their own. “Any of that would negate the need for human intervention and the cost of that human intervention.”

There have been tantalizing signs of such a possibility. In 2018, a massive winter storm washed urchin tests up onto beaches along the Mendocino coast. “That made me think, ‘Oh, maybe it’s happening,’” Carr says. “But we haven’t seen evidence of that yet.”

There’s another problem: The urchins simply won’t starve to death. Like zombies in some state of hibernation, the urchins shrink as they slowly consume themselves—first their fatty gonads, then their tests—and subsist on what little nutrients they absorb from the current.

Although a natural solution to kelp’s decline seems unlikely, it’s important to consider the implications of doing nothing. Given how widespread the kelp die-off has been, it’s reasonable to expect that nothing—no human intervention—is exactly what will happen in most areas. This doesn’t mean kelp will never recover. Sergey Nuzhdin, a biologist at the University of Southern California who studies kelp genetics, stressed that kelp is a tremendously resilient species—it evolved to grow in rough, coastal waters, where change is often the only constant. So it’s possible that something will shift the needle and kelp forests will return on their own. “But we’re talking many years before this happens,” Carr says.

When you view the situation in this light, you start to wonder which species is more threatened—the kelp, or the fishermen and divers who view it as an important part of their heritage and livelihood.

One criticism of urchin removal efforts is that ridding the entire North Coast of purple urchins is both unrealistic and inefficient. In response, some scientists have proposed another path: Let the urchins’ predators—sea stars and sea otters—do the work for us.

Jason Hodin is a marine biologist at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Lab on San Juan Island. In collaboration with the Nature Conservancy, Hodin is breeding sunflower sea stars in captivity to reintroduce them onto reefs, as part of a feasibility study. The sea stars in his lab are survivors from areas hit by wasting syndrome, so they likely have some degree of resistance to it—and their offspring could be even more immune.

The project has been slow going. Because the sea stars are now rare, just collecting and holding them in captivity made Hodin nervous. Trying to get them to spawn sounded to me borderline barbaric (the process involves amputating a sea star’s leg and injecting hormones directly into its gonad). Last November, Hodin successfully fertilized sea stars he’d collected in Washington. He now has his first generation of juveniles, but it’s still years before they can be released into urchin barrens. There is only one publication documenting that sunflower stars have been raised to the juvenile stage in captivity—by a master’s student who graduated from the University of Washington in the 1960s—and no one has ever tried to reintroduce sea stars before.

Another urchin predator, the sea otter, is better understood. Scientists recognized the sea otter as a keystone species in California’s kelp forests as early as the 1970s. The species once numbered in the hundreds of thousands and could be found from Alaska to the Baja Peninsula. It’s currently confined to a stretch of California’s Central Coast between Monterey Bay and Point Conception—just 13 percent of its historic range.

Sea otters are the smallest marine mammal and the only one that doesn’t store energy in reserves of blubber. To keep warm, they need to consume a quarter of their body weight in food each day. This may explain why otters in Monterey Bay don’t dive for urchins in barrens, according to dissertation work by Joshua Smith, one of Carr’s Ph.D. students: The emaciated urchins are basically empty shells devoid of calories. But otters have prevented existing kelp forests from slipping into urchin barrens. Brent Hughes, an ecologist at Sonoma State University, has gone so far as to say that if otters had existed along the North Coast in 2013, there would likely still be kelp forests there today.

Hughes’ argument is based on a relatively well-accepted ecological rule known as the diversity-stability theory, which says the more species in a given ecosystem, the more resilient that ecosystem will be to change. It’s a pattern that plays out in kelp forests up and down the California coast. In Southern California, a network of marine protected areas—the very places the Watermen’s Alliance fought to prevent—supports healthy populations of lobster and sheepshead, which continue to eat urchins long after wasting syndrome has taken out sea stars. And along the Central Coast, a thriving otter population has kept urchins from completely overtaking those kelp forests.

“Otters continue to play a really important role in the persistence of kelp forests here in Central California,” says Carr. “One can imagine they would have done the same thing in Northern California.”

For fishermen working to restore Northern California’s kelp forests, though, otters are a political nonstarter. Otters eat the same things we do—crabs, abalone, urchins—so their reintroduction would likely contribute to a decline in local fisheries. Taylor White, a Ph.D. candidate at UC Santa Cruz studying otters and abalone in southern Alaska, told me otters have a disproportionate effect on any ecosystem they exist in: “Just one otter can have a huge impact.” It’s possible the North Coast abalone fishery existed because otters are no longer there. Along the Central Coast, similar fisheries don’t occur—the otters just eat too much.

Even mentioning otters seems to unnerve those working to restore North Coast kelp forests. “The idea of reintroducing otters has no bearing in reality,” Koe says rather quickly when I bring up the idea. Hughes cites the debate between ranchers and conservationists over the reintroduction of wolves throughout the West as a comparison; that debate has largely left the realm of science and now exists in the realm of emotions, with both sides fighting a high-stakes battle for public opinion. “Given the controversial aspect of the otter question, it’s almost a distraction at this point,” says Gleason, the Nature Conservancy biologist. “Fishermen are going to play a big role in helping recover this ecosystem. We don’t want to make this an uphill battle.”

Last September, researchers at NOAA, tracking a new “blob” forming off the West Coast, warned that such marine heat waves will become more common. Suddenly, scientists were faced with the possibility that they could succeed in restoring kelp forests only to have them die off when another heat wave comes through.

Many of the stakeholders I spoke with were explicit about their goal to return Northern California’s kelp forests to pre-2012 conditions. But it’s hard to square that outcome with the disruptions we’re already witnessing—climate change, marine heat waves, and the viruses they exacerbate. After all, the kelp forests of a decade ago were not resilient to change. The question is: Would the diverse kelp forests of a century ago—with sea urchins, abalone, sea stars, and otters—fare any better amid climate change?

Restoring that kelp forest doesn’t have to exclude fishermen. In southern Alaska, where White studies the relationship between otters and abalone, the Marine Mammal Protection Act gives Native Alaskans the right to hunt otters, which they do—currently more than 1,000 each year—often, White told me, in order to prevent the otters from settling in coves where they would decimate abalone and crab populations.

It’s hard to envision a future when Californians would condone hunting otters, but it might be a compromise that conservationists should consider. For the last few years, the Central California sea otter population has wobbled around 3,090—its threshold for being delisted under the Endangered Species Act. Successful future reintroductions, such as along the North Coast or in San Francisco Bay, would surely put it over the top. The waters off the North Coast could then be organized into a patchwork quilt consisting of marine protected areas, where otters and the role they play in maintaining healthy kelp forests are protected, and areas set aside for fishing, where otters could be hunted. “Maybe we need to start thinking about how to spatially manage otters in a way where you’re protecting their populations and roles in the ecosystems in some areas, but you’re also protecting fishery services in other areas,” Carr says.

At some point we will need to acknowledge the ecological role of otters, says Dominique Kone, who as a master’s candidate at Oregon State University wrote his thesis on otter reintroduction. “Oftentimes, when we talk about otter reintroduction, we can get lost in the nitty-gritty,” says Kone, now an ecologist with the California Ocean Science Trust. “But we also need to realize that these coastal areas are missing a really important keystone species that has, essentially, co-evolved with kelp forests. If we return that species, a lot of things that are out of balance might fall back into place.”