Last month, as Hurricane Irma was bearing down on Florida, a crowd of international designers, scientists, and policy-makers gathered at a warehouse-turned-winery at the Port of Richmond.

They were there to launch a new effort called Resilient by Design to consider how the Bay Area will adapt to seas that could, at the extreme end, rise 10-feet higher by the end of this century. Ten winning design teams have until May to come up with shovel-ready projects, from blueprint to community support and a financing plan. The crowd drank glasses of wine, toasted the challenge, and drew comparisons to events playing out on the evening news.

We can’t afford to see Harvey, Katrina, Sandy, and Irma from a distance,” said Richmond’s mayor Tom Butt. “The same type of destruction we see on T.V. is laughing at our doorstep. We need a new approach, we need to think differently, innovate, and work together to adapt.”

It’s easy to feel our environment is gentle and temperate in the Bay Area — somewhere between a t-shirt and a hoodie weather. It’s a mistaken belief, says Bay Area historical ecologist, Robin Grossinger. The potential for a natural disaster is real, and we haven’t properly planned for it. In fact, we’ve anti-planned for it. Throughout the past 150 years as we’ve pushed our footprint into the Bay, building neighborhoods and highways, airports and bridges, we’ve been living in an extraordinary stable time and that’s coming to an end.

It’s an odd historical anomaly in the system,” Grossinger said. “The Bay’s going to keep rising and this is a period when we have made it much smaller. We’ve established this construct of the shoreline as this fixed place.”

A 200-year mega-flood, the steady march of sea level rise, not to mention a major earthquake, and wild fires along the so-called “wild-urban interface” — these are in our future. All this and the added pressure of 2 million more people in our region by 2040.

After Hurricane Sandy gave New York City a wake-up call in 2012, an effort was launched called Rebuild By Design that garnered $920 million in federal disaster relief funds to launch projects to remake the waterfront with berms, wetlands, and a built reef. The Bay Area’s Resilient By Design (RBD) is modeled off New York’s efforts, though with a fraction of the public funding available and a preemptive approach to disaster planning. It’s an acknowledgment that the problems coming down the pike are so large as to require a reconsideration of the Bay’s shoreline.

“I’m just a scientist,” says Andy Gunther of the Bay Area Ecosystems Climate Change Consortium, “and I struggle to provide the visions that can stimulate our elected officials and the public to rally for the kind of changes we need to make.”

Seeded with $4.6 million from Rockefeller Foundation, the design challenge has attracted some all-star talent excited by the prospect of working on the stage of the San Francisco Bay. Among them, Danish futurist Bjarke Ingels, whose portfolio includes such feats as a water-to-energy plant in Copenhagen with a ski slope on top, as well as the design of the world’s first hyperloop in Dubai (he has also designed New York’s ‘Big U’). Also in the mix is Dutch architect Nathalie de Vries, whose firm created a 10-story floating apartment block in Amsterdam harbor in 2002. By mandate, each team has local representation and a process for community input to keep the effort grounded in the Bay Area.

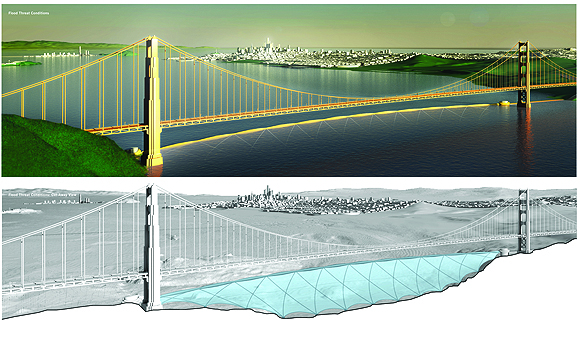

That’s assuaged concerns that the effort won’t produce realistic proposals. The last time the Bay Area opened itself to an international design competition, the result was a series of spectacularly whimsical ideas, including a submerged, cable-reinforced “bladder” under the Golden Gate Bridge to hold back extreme tides. That was 2009 —when fantasies could take flight in the hopes that the world could reduce carbon emissions enough to put off the need for adaptation.

The projects were imaginative and inspiring and provocative but not really very pragmatic,” says Jon Christensen, a professor at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and a member of Team UPLIFT. “I think this effort reflects the distance we’ve come. There are places around the Bay Area that are going to experience unprecedented annual flooding in the lifetimes of people 40 and under today — and that is by mid-century.”

RBD’s executive director Amanda Brown-Stevens says that Bay Area voters’ approval of the Measure AA tax last year for wetlands restoration and sea level rise mitigation positioned the region well for this design challenge.

“We were having conversations on and off with the Rockefeller Foundation, and when Measure AA passed that was when the Rockefeller team took a second look,” Brown-Stevens says. “Their biggest question was ‘how are those projects going to be funded if they don’t have that disaster funding?’ But this region came together and over 70 percent of folks were willing to tax themselves for resilience.”

Still, Measure AA, which will disperse $500 million over 20 years, will not be enough to pay for the RBD projects, and it is stretched across many other ongoing initiatives along the Bay. Funding the proposals with federal money, given the current political climate in Washington, is iffy. But private financing could be available for projects with a development component, and meanwhile, a $4 billion parks and water bond for California may be on the June 2018 ballot.

“There’s no magic bullet in financing,” says Brown-Stevens, adding that a mixture of Measure AA funding, local infrastructure bonds and the potential approval of a state parks bond could bring these design projects across the finish line.

This fall’s immense North Bay wildfires and the record-setting heat waves have revealed new climate-related vulnerabilities in the Bay Area that go beyond the more obvious threats of sea level rise. The design teams will still focus their projects on flooding and soil liquefaction along the Bay, but Brown-Stevens says she hopes RBD’s model of regional collaboration has a spillover effect into other risks from natural disasters.

“We’re moving the conversation forward toward building regional resilience and regional structures.”

The design teams have a big lift in front of them to get these projects close to shovel-ready by May. After touring numerous locations around the Bay in the upcoming weeks, design teams will come up with three to five rough sketches of possible projects. RBD officials will then match each design team to a specific location with representation in each of the Bay Area’s nine counties.

So, what can be done? Bay conservation managers and scientists who are advising the teams are emphasizing a “soft edge” to the shoreline, rather than seawalls and levees. Featuring high on their wish list are tidal marshes, a major part of the Bay’s historical shoreline, which act as a sponge to rising waters and create habitat for numerous species.

For two decades, scientists and conservationists have been painstakingly creating marshes toward a goal of 100,000 acres in the Bay by 2030. But the pace of sea level rise (and the additive effects of high tides and storm surges) means most of these wetlands will be erased by 2100 unless new measures are put in place to shore them up. Experiments with new solutions are underway—for example, a ‘horizontal levee’ that recreates wetlands at a San Lorenzo waste treatment plant — but there’s a sense of urgency to do more and faster.

“We have a lot of incipient prototype efforts with potentially important approaches,” Grossinger said, “but we haven’t gotten to the level of scale or ambition to have the impact needed. I’m excited about these teams. This work could take it to the next level.”

But tidal marshes aren’t going to cut it for some of the most critical spots along the Bay. With only 2 feet of sea level rise, the runways at SFO start to go under and the eastern onramp to the Bay Bridge will be inundated (yes, the same section that was completed a few years ago). These are spots where the design teams are also looking to help.

“We’re not going to let the toll plaza flood,” Gunther said about the use of traditional levees in some areas. “We’re going to draw the line in some places — at least through mid-century.”

Mid-century — about 30 years from now —hangs out there like a great question mark. Sea level rise projections for the Bay Area diverges sharply at that date, and where we end up on the scale of 1-foot to 10-feet by the end of the century depends on the accuracy of the scientific predictive models and what the world does about curbing emissions. When designers asked how much sea level rise they should plan for in their designs, Klaus Jacob, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, advised them to build for the expected lifetime of the structure.

Designers and planners, in a sense, can barely anticipate a future beyond this because it involves the unfathomable prospect of retreating from the shoreline.

“There is an underlying tension here and I hope to see some of these design plans anticipate this,” Gunther said. “Is there a way the design is phased so that as sea level rises, the site retains its resilience and it keeps functioning? If we can acquire and plan transition zones, those shorelines will take care of themselves. Eventually I think coastal development will turn into coastal un-development in a lot of places.”

Nate Kauffman, a landscape architect at UC Berkeley, put his hand to paper and sketched out his vision of a new Bay shoreline. In his 2015 publication, Live Edge Adaptation Project, his sketches show beaches, a barrier island, boardwalks across marshes and campfires in the sand. It’s idyllic, even utopian, and implies a Bay Area that has fully embraced life along the Bay, made safer from higher, stormier seas by mud, water, and vegetation.

Kauffman, a member of the All Bay Collective design team, sees Resilient By Design as a chance to connect people to the Bay so they feel invested in what happens to it. On a recent tour of Arrowhead Marsh with the design teams, he heard from nearby Oakland residents about how impossible it is for some people to get to these marshes.

They cannot ride their bikes down the street because metal scrappers are dropping things on the ground, there’s no pedestrian bridges, and no public transportation,” Kauffman said. “All these overlaying social factors are happening at the same place as this wounded landscape.