Our October-December 2016 story looks at the argument about whether eucalyptus in the East Bay Hills are dangerous. But how did they get here in the first place?

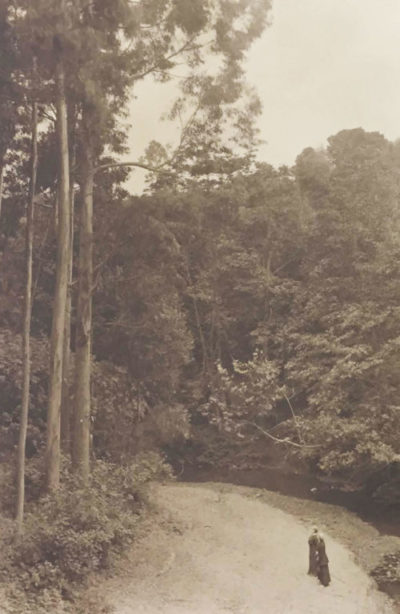

At the end of the 19th century, the country was gripped by fears of a timber shortage, writes historian Jared Farmer in his book Trees in Paradise. This expected problem seemed especially likely in the burgeoning Bay Area, where local timber supplies were scarce. Fast-growing Australian eucalyptus didn’t just seem like a solution, it seemed like a goddamn miracle—at least, according to Havens’ Mahogany Eucalyptus & Land Company’s 1911 prospectus. Filled with sepia-tone photos of men wearing suspenders and bowlers and standing next to trees, the pamphlet lauded the eucalypts as “of more glorious hardness” than teak, mahogany, ebony, hickory, or oak, with wood suitable for cabinets, railroad ties, dock pilings, boats, paving blocks, telephone poles, and violins; as a bonus, the trees were “an inspiration to the artist” and possessed “healing odors.” The photo that accompanies this latter claim shows two women in long black dresses—presumably just off their fainting couches—gazing at a stand of eucalyptus.

Havens’ blue gums were grown from seed collected by botanist Andrew Murphy of Woy Woy, New South Wales, Australia (“a most reliable man,” per the pamphlet). Eucalyptus-nursing was by then a flourishing trade. Settlers had begun planting eucalyptus in California in the mid-1800s, Farmer writes, with planting peaking in the 1870s and again between 1907 and 1913. They eventually planted more than 400 different species of eucalypts, but the vast majority of trees planted were blue gums, selected for their speed of growth. The trees were planted as windbreaks and shade trees, along roadsides and in towns, to add beauty to a California largely bare of trees—but most of all as a source of fast lumber. A timber shortage was a far more existential threat than it sounds like now, as Farmer points out; the world of that century was built on and powered by wood. “In the industrial age of wood, it did not seem far-fetched to imagine future travelers walking on eucalyptus street-paving blocks, riding in eucalyptus buggies, and driving automobiles on wheels with eucalyptus spokes.”

In the end, of course, the timber shortage never came to pass. Blue gum, meanwhile, fell far short of expectations. “The Company now sees plainly that it possesses a source of emolument [money] higher than that of the average gold mine,” the prospectus concluded, but by then the gambit was nearly up. Havens abandoned the tree plantations just two years later, in 1913, after planting 14 miles of the Berkeley-Oakland ridgeline with some three million trees (mostly blue gums); Farmer writes that a Department of Agriculture report from that year gave official weight to what had already become obvious: Blue gum made lousy lumber. It cracked and split as it dried, and it was suitable only for firewood. After Havens’ death, the plantations were left to grow wild, and in the 1930s, the East Bay Regional Park District took possession of many of them. The trees are now 100 years old; it seems possible that some will make it to 200.