Misha Leong cannot find what she’s looking for. She’s crouched beneath a stand of tall eucalyptus trees in the Tilden Nature Area, the ground around her littered with dozens of bark scrolls that she has spent the last half hour unfurling. She pries open yet another tight, three-foot-long tube, peers inside, and sighs. “I’m starting to suffer from performance anxiety,” jokes the California Academy of Sciences entomologist.

Leong and Tilden Nature Area naturalist Trent Pearce are hunting spiders. It’s not that this morning’s expedition hasn’t turned up any of the eight-legged creatures—we’ve surprised members of three different genera hiding in the scrolls, the sudden burst of sunlight sending them darting for cover. But none of those creepy-crawlies are on our list. We’re after Segestria.

The small, cagey arachnid is known for evolutionarily primitive characteristics not seen in modern spiders. Segestria has retained two openings, called spiracles, near its lungs, whereas most modern spiders only have one. The spiracles likely helped spiders in their tricky transition from living in water to living on land more than 400 million years ago.

But spiracles are far from identifiable on the dime-size spider while we’re in the field, so we’re looking for other telltale signs—it’s got six eyes, instead of the usual eight, and its legs are odd. The “tube-web weaver” (as this spider is also called) has appendages adapted for living in cylindrical spaces, with the first three pairs, instead of the typical two, directed forward. This arrangement keeps more legs in front to better capture prey. At night it waits near the tube’s edge, threads dangling from its three pairs of forward-pointing legs ready to detect insectivorous passersby. When an unlucky bug trips the alarm, the Segestria shoots out and snags its dinner, bringing it inside the tube to devour.

The Bay Nature Guide To Webs and Spidering

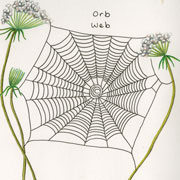

Spider webs can be found in almost every imaginable place — even underwater — and have allowed spiders to populate every continent except frigid Antarctica. Want to find them for yourself? Check out Bay Nature’s guide to spidering, with an illustrated guide to the five most basic forms of spider web.

All spiders are predators with eight legs, a body divided into two regions, and poison-laden fangs. Spiders also all spin silk. Approximately 3,000 species of them occur in the United States; the Bay Area is home to more than 1,500 of those. Their voracious appetites help keep insect populations in check, and they themselves provide sustenance for a bevy of larger animals, including lizards, frogs, birds, and mice.

Today we’re seeking out some of the Bay Area’s most noteworthy eight-legged inhabitants: Segestria and a host of other arachnids that have maintained primitive features seen in the earliest spiders, including strange claws, a rare silk-spinning organ, and unusual fangs. More than two dozen such species occur in the Bay Area alone—a region that is the world capital for both trapdoor spiders and spiders that produce woolly webs, a silk-spinning strategy that dates back at least 200 million years. California’s triumvirate of rugged topography, geographic isolation, and mild climate during the last ice ages account for the preservation of so many primitive attributes statewide and in the Bay Area. Surrounding us are vestiges of an ancient time, if you know where to look for them.

California’s triumvirate of rugged topography, geographic isolation, and mild climate during the last ice ages account for the preservation of so many primitive attributes statewide and in the Bay Area. Surrounding us are vestiges of an ancient time, if you know where to look for them.

That doesn’t mean individual spiders scuttling over the hills and coast are exact replicas of their ancestors. “Everything that’s alive today, even if we call it primitive, has changed from what it was like millions of years ago,” says Darrell Ubick, a renowned entomologist at the California Academy of Sciences and Leong’s colleague. “Life is constant change.”

People rarely see most of these spiders, says Joel Ledford, an entomologist at the University of California, Davis. “They’re odd little spiders that live in specialized habitats.” Still, with a few pointers, Ubick reassures me, it’s relatively easy to locate several of these unique species in the outdoors.

“Found one!” cries Pearce, standing beside a towering redwood. After failing to find any Segestria in the eucalyptus-bark scrolls, Pearce has already switched to a new quarry. He’s pointing to a hand-size, fuzzy web with a gaping hole in the middle that’s strewn across the rough bark. We rush over excitedly and see…nothing. There’s no spider in sight.

That’s because this web belongs to a Callobius, Pearce explains with a naturalist’s seemingly endless enthusiasm and patience (most spiders mentioned in this story are referred to by genus name only, because it can be difficult, even for experts, to identify them without a microscope). These nocturnal hunters, six species of which inhabit the East Bay, hide behind the bark during the day. At night they emerge, lurking by the hole in their web, waiting to pounce on insects that get tangled in the trap. Pearce gently pries back the bark, revealing a plump, three-quarter-inch brown beauty tucked in the wrinkly wooden folds.

This might be a good time to mention that Pearce and Leong are self-proclaimed scaredy-cats when it comes to handling spiders. Black widows are the only spider in the Bay Area that can send a victim to the hospital for antivenin treatment, but plenty of arachnids found here deliver a bite painful enough to warrant caution. “So we won’t touch,” Pearce explained before we set out this morning. “We’ll poot.” A pooter, technically known as an aspirator, consists of a three-inch-long hard plastic cylinder, a screen, and a long rubber tube. The user places the rubber tube to her lips, positions the cylinder near the spider, and sucks it up with a poot-poot-poot inhalation (the screen ensures there’s no risk of swallowing the prey). The captive is then deposited into a vial for closer inspection.

So when Pearce exposes the Callobius, Leong whips the pooter from around her neck and hoovers up the target into the clear tube. As she goes to release it into the vial Pearce is holding, however, it skitters down the outside edge. They both shriek and Pearce drops the container. After a bout of nervous laughter, they quickly find the spider on the ground. Poot attempt number two is a success.

Seen through a magnifying lens, the captive’s beady eyes pop. But the structure we’re looking for is underneath on its abdomen: the cribellum. This flat spinning organ arose early in arachnid evolution, but has been lost in the majority of spiders. Most arachnids produce glue that makes their webs sticky, whereas Callobius and other so-called cribellate spiders have plates covered in tiny spigots that produce thousands of strands of silk. Instead of relying on glue, cribellates produce a mass of “woolly” web strands to entangle their insect prey—like the gauzy webs guarded by plastic spiders during Halloween. Callobius’ fuzzy snares have an almost bluish tint and are easy to spot on redwood trunks, even as their makers remain safely concealed from daylight and prying eyes.

Most of the other spiders on our list of primitive species are similarly night stalkers. But Pearce has an idea where we might find another, even while the sun is still high in the sky. We follow him to an irrigation valve box buried in the ground. We squat, Leong at the ready with a specimen box and pooter, as Pearce, lit flashlight in his mouth, lifts the lid. A fat spider makes a break for it, but the duo swiftly captures it. The two-inch-long arachnid, which is an almost translucent mauve color with a gray abdomen, is a Titiotus. Its claws, Leong explains, are its peculiar ancestral feature.

The most primitive spiders have three claws at the end of each leg, while more advanced ones have two claws and usually a “tuft.” The tuft is comprised of tiny bristles, called setae, which each have thousands of microscopic hairs that generate a stickiness on the molecular level, allowing spiders to climb smooth surfaces (this is also how geckos cling to glass by a single toe). Titiotus has tufts and a much-diminished third claw, suggesting it is in a state of transition between the old and the new. “It is one of the few spider genera in the world that has claw tufts and vestigial third claws,” Ubick tells me later. To find a Titiotus, he suggests flipping over logs or big rocks. Or, he adds, check your cellar.

To understand why California is so rich in spiders with primitive features, you have to go back in time—way back, to the geologic upheaval that sculpted the state’s rugged landscape.

When the supercontinent Pangaea broke up some 200 million years ago, the western edge of North America began to expand and enter a period of tremendous geologic activity. “The growing mountains and river valleys opened up new habitats for some species” over millions and millions of years, says Ubick, “but also acted as barriers to others,” greatly increasing the number of species. As a wealth of plant and animal diversity evolved in this richly complex landscape, it was sustained by the increasingly Mediterranean climate that emerged over the last several million years.

During roughly the same period, glaciers grew and contracted through ice ages, freezing out animals across much of the continent. But areas of California, including pockets west of the Sierra and along the coast, remained mild and ice-free, acting as refuges. When the glaciers retreated, some of the survivors stayed in their niches, while others spread—though natural barriers checked their movement. “California is very much like an island,” says Andrew Fowler, a geologist at the University of California, Davis. “Surrounded by ocean, desert, mountains, it is very challenging for species to cross.”

The result is more plant and animal biodiversity in California than in much of the rest of the lower 48 states. “These large-scale forces clearly affected the whole biota,” says Ubick. “In each group, there’s some weirdness.” He points to a variety of primitive creatures, including the coastal tailed frog; the mountain beaver, the only living rodent with certain ancestral cranial and muscular features; and Timema walking sticks, which have no wings and reproduce asexually. The same holds true for some spiders, he adds. California may be home to the world’s largest number of cribellate species, which create the woolly webs—with more than a half-dozen found in the East Bay alone. “The cribellum has been lost in spiders in many other parts of the world, except Australia and New Zealand,” Ledford says.

The state is also one of the world’s hot spots for mygalomorphs, a primitive suborder of spiders that includes tarantulas. Tarantulas are among the evolutionarily oldest arachnids, and their partially segmented abdomen is a holdover from tens of millions of years ago. Among their fascinating features are their fangs, which point straight down. While more advanced spiders use their fangs like pincers, these creatures take a pickax approach, swinging the weapons downward to pierce their prey. The East Bay is home to other mygalomorphs that build ingenious houses. To see them, Ubick says, it’s best to venture out at night.

A coyote howls as the last daylight drains from the sky in Briones Regional Park near Orinda. The impending darkness is exactly what Pearce, two friends who are also naturalists with the East Bay Regional Park District, and Ken-ichi Ueda, co-founder of citizen science reporting site iNaturalist, have been waiting for. The members of the posse, who regularly conducts nighttime biodiversity surveys, don headlamps and descend from the Bear Creek parking lot into a nearby ravine.

Sierran chorus frogs dart about in the leaf litter, underwing moths float past our heads, and gooey slug slime glints in the light cast from the group’s foreheads. Pearce points out the clever home of an Antrodiaetus riversi. Commonly called a turret spider, this mygalomorph uses silk and woody debris to build a turret, or hollow cylinder, atop its burrow. It sticks out of the steep bank like a short, dirt-colored chimney—easy to miss if you aren’t looking for it. This ingenious construction protects the burrow from flooding and provides the inhabitant with a built-in dinner bell.

“Let’s see if anyone is home,” says Pearce.

“Tickle time?” asks Ueda.

“Tickle time,” Pearce agrees. (They’ve spent a lot of time spidering together.)

Pearce picks up a twig off the ground and gently rubs it along the edge of the turret. Everyone waits in silence, headlamps focused on the movement, which sends vibrations down the structure, alerting the spider that a tasty insect might be lingering outside. Seconds tick by. Suddenly, a gasp from the group as a dark blur bursts from the tube, grabs briefly at the stick, and darts back inside. “That,” says Pearce, “is a turret spider.” This particular individual couldn’t be coaxed into a repeat performance, but a few of its neighbors were willing to hang out in their entrances for longer, their eyes shining, like a cat’s, in the dark.

Still, the glimpses were too fleeting to make out the turret spiders’ primitive features. They have the mygalomorph’s downward-pointing fangs, but their respiratory system is unique. Turret spiders have two—instead of just one—pairs of book lungs, each lung with a set of thin overlapping flaps, like book pages, stacked inside a cavity in the abdomen. The inside of each flap is filled with blood and the outside is exposed to air, allowing the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. While the marble-size spiders might be small, they’re long-lived. They take several years to mature, and females may live for many years beyond that.

Amid an apartment complex of turret spiders (females stick close to home, while males wander), Ueda spots a trapdoor spider (Promyrmekiaphila or Aptostichus). Another mygalomorph, it builds a house similar to that of the turret spider, but capped with a leaf or other camouflage. When a potential meal passes by, the occupant lifts the trapdoor and snatches it. “They are practically impossible to see,” says Ueda, pointing out what at first glance looks like nothing more than a leaf on the ground. He tries the tickle trick. After a moment the spider partly raises its leaf-door to check for its ersatz dinner, then quickly drops it shut. It slams so quickly that we couldn’t see the vestiges of unfused segments on its abdomen, similar to that in tarantulas.

Some trapdoor spiders are named after famous folks, including Edward Abbey, Stephen Colbert, and Angelina Jolie (and Ubick says there are still many not-yet-described species), but determining what, if any, name belongs to this particular one would require capturing it for inspection in a lab, which the naturalists are reluctant to do. “Trapdoor spider,” says Pearce. “Good enough for me.”

Some trapdoor spiders are named after famous folks, including Edward Abbey, Stephen Colbert, and Angelina Jolie (and Ubick says there are still many not-yet-described species), but determining what, if any, name belongs to this particular one would require capturing it for inspection in a lab, which the naturalists are reluctant to do. “Trapdoor spider,” says Pearce. “Good enough for me.”

By the time we climb out of the ravine, the moon is high in the sky. As we walk back to the cars, our headlamps pick out the eyes of wolf spiders, shining like glitter in the grass. A big, black spider catches Ueda’s attention. He shows it to the rest of us with a laugh: it’s a plastic toy, probably dropped by a child, and the only specimen collected by a bunch of spider hunters that night.

Pearce hasn’t always been enamored with arachnids. As a kid, he once came across a fishing spider in his grandmother’s house in Tennessee. “It was as big as a dinner plate,” he recalls. And, though he didn’t know it then, the piscivore wouldn’t have hurt him. “She squashed it, and guts went everywhere.” Pearce says that instinctual response, to crush the eight-legged creature, is something he aims to subdue in the spider classes he teaches to park visitors.

One of the eight-legged creatures his students are sure to see is the impressive Calisoga he keeps in his office. At first glance, this silver-gray mygalomorph is easy to mistake for a tarantula. It’s that big. On the upside, that makes them simpler to see in the wild, says Steve Lew, an entomologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “They’re huge. Males are out wandering around most of the year—unlike tarantulas, which only come out to mate in the fall,” he says. “You can often spot a female’s burrow. If you see a big hole, maybe there’s a Calisoga in it.”

Females tend to stick to their burrows, which they dig themselves, or they’ll take up residence in an empty rodent hole or rotting tree root. Mating season usually begins after the first fall rains, and courtship is the fella’s duty. His wooing consists of quivering his legs as he enters a burrow and gently touching the female with his forelegs. If she’s game, she’ll indicate her consent by raising her forelegs and spreading her fangs. In summer the female constructs her lone egg sac, attaching it to the roof of her burrow; the spiderlings hatch two months later. But the female never leaves—unless her burrow is disturbed. That’s likely what happened to the one living in Pearce’s office. Nearby homeowners found her in their basement a couple of years ago, amid a big road construction project.

As Pearce, in his office, relates her history, he lifts the terrarium lid so we can get a better look. “They have a bad reputation as being vicious, and I’m sure a bite would hurt like hell,” he says, “but she’s pretty calm.” As if on cue, she rears back on her hind legs and bares her fangs. We instinctively take a step back. “Maybe that bad reputation isn’t so undeserved after all,” muses Pearce.

I decide not to find out. Count me in on team scaredy-cat: fascinated to learn more about these incredible creatures, but from a safe distance.