Text and research by the California Center for Natural History

Ecosystem Engineers

Amid the rock piles along the bayshore, scampering through grassy fields in the hills or the flatlands of the Bay Area, you will find California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi), those perky, curious rodents native to the state and crucial to the health of grasslands. It’s their extensive burrows that both annoy farmers and shape ecosystems. The squirrels often dig horizontally into hillsides, creating tunnels that lead to food storage chambers, sleeping areas, and nurseries. Side tunnels end right below the surface, allowing a quick escape from underground predators. These elaborate subterranean homes can damage crops, building foundations, and levees, but their burrowing also improves the soil by loosening and aerating it, increasing water absorption, and adding nutrients. The moist, cool burrows provide shelter for more than 200 species, from frogs to burrowing owls, and the federally endangered California tiger salamander, which spends much of the year living within the burrow systems but surfaces around November to breed.

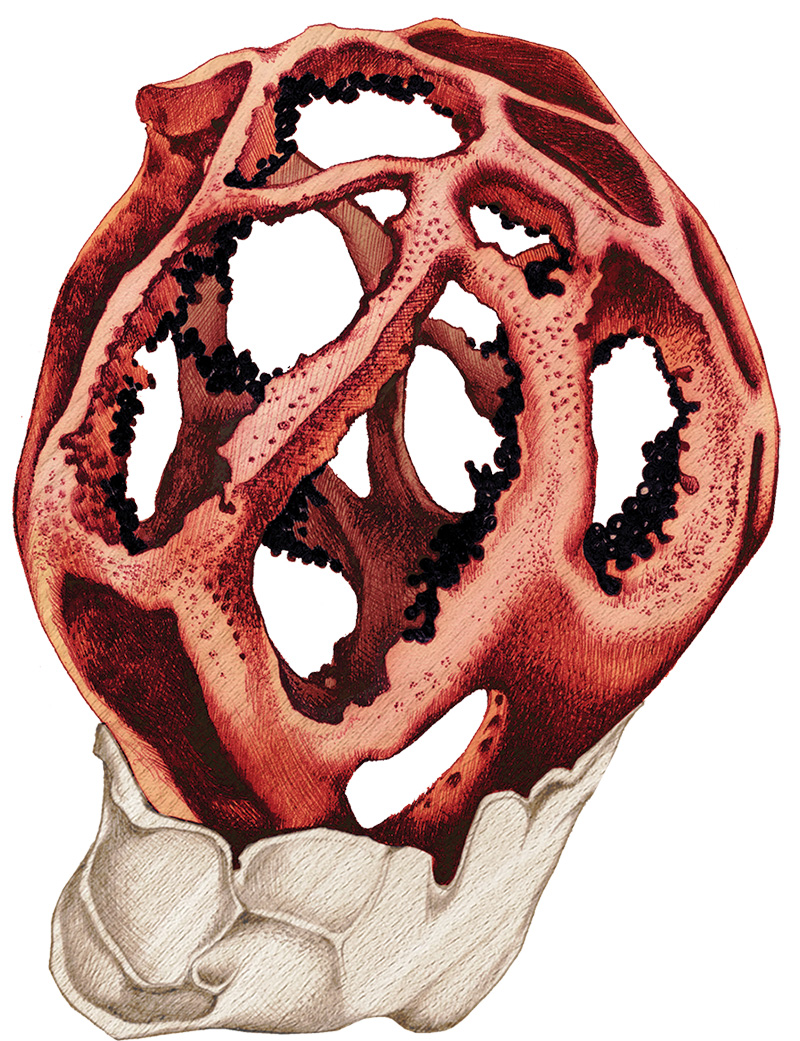

Red Cage Fungus

You’d be forgiven if you mistook this strange fungus (Clathrus ruber) for a red wiffle ball from outer space. Maturing as a small white “egg” to a little bigger than a ping-pong ball, the fruiting body then develops into a distinct hollow lattice. Get close to smell the rotting meat bouquet that attracts flies, which buzz around the inside of the lattice and get covered in sticky dark spores, helping to spread the fungus. Called “witch heart” by people in the Balkans, where it’s native, this fungus can be found feeding on decaying plant material like mulch or downed trees.

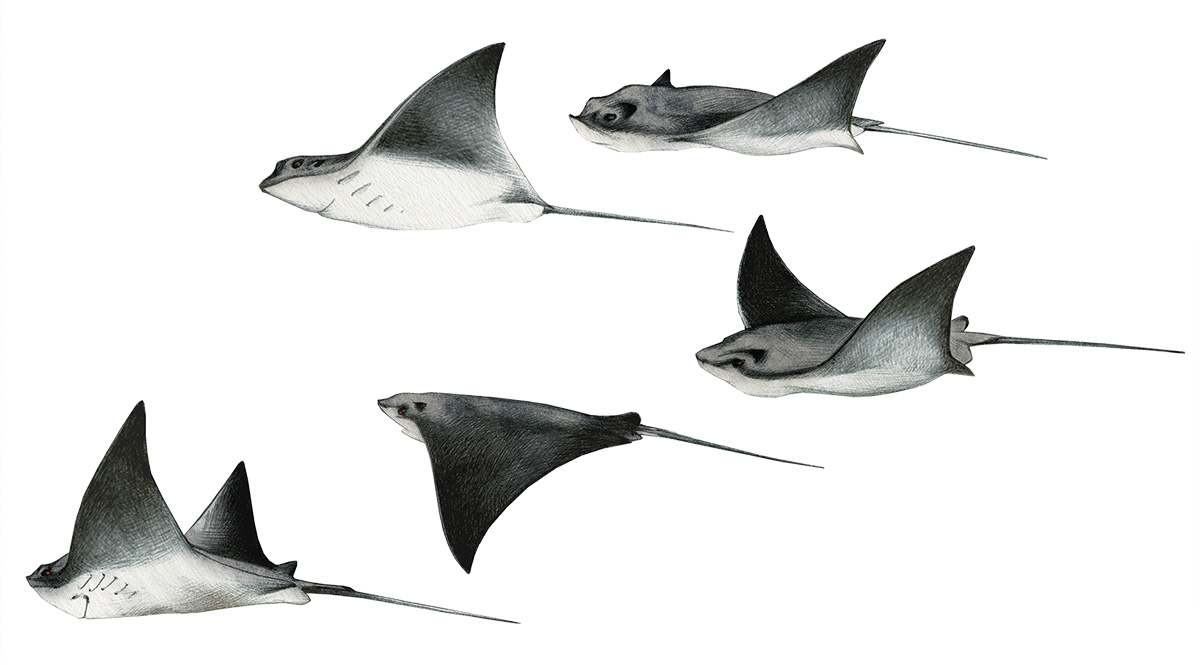

Into The Great Blue

Fall is a season of transition for California bat rays (Myliobatis californica). Throughout summer, the adults give live birth to young in shallow, sandy-bottomed estuaries like Tomales Bay and Elkhorn Slough. The larger mature females can birth 10 to 12 pups, born tail-first with wings wrapped around themselves! Adults and pups hang around the nursery grounds until fall, when water salinity drops with rainfall and the colder months set in, heralding an exodus from the breeding areas out to the Pacific.

Nuts

Along Northern California rivers and streams grows a native black walnut tree whose fruits ripen to green around October, then drop and turn black. People who’ve managed to hull and shell the nuts claim the taste is worth the ridiculous amount of work involved. Crows and squirrels seem to like them too, but there hasn’t been much ecological study of these trees. Most research focuses on the Juglans hindsii species’ extreme rarity due to hybridization, but research by UC Davis biologists in 2018 has thrown that rarity into question, finding genetically pure J. hindisii trees to be common in Contra Costa and Napa counties, among other places.

Moving to Your Hood

Is that…Elvis, no, Little Richard, cruising the pond in the local park? Um. Maybe. But more likely it’s a male hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), those pompadour-sporting ducks that arrive here around November, a classic fall migrant that winters in the Bay Area. Although that may be changing—hooded mergansers are now also breeding in Northern California, including Sonoma County, a 2006 study found. Look for these small ducks around lakes and ponds this fall feeding on fish; it’s the only North American duck that does so—which helps explain its serrated bill and keen underwater eyesight … but not the fantastic crest of feathers.

Mother Crab

In the fall, an adult female Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister) looking to lay eggs will scuttle along the sea or bay’s sandy bottom to find a spot to burrow down. She’ll begin extruding a mass of bright orange eggs that stick to her abdomen and both will stay buried through winter until the eggs hatch as larvae in spring. Should you come across a female while crabbing after the season starts this November, let her continue her good work. You can recognize a female by her round abdomen flap; males have a long, triangular one.