In a boat floating on San Pablo Bay, Emily Miller prepared her scalpel. Just 15 feet below, her quarry lurked in the murk, probing the mud with its dangling chin-whiskers, searching for clams to guzzle whole with its toothless, tube-shaped mouth. A net loomed behind it, ready to snag the behemoth.

Related

After 2022’s Fatal Algal Bloom, Scientists Fear the Bay’s Sturgeon Could Go Extinct

In an open letter, they called for California to consider making white sturgeon fishing catch-and-release. (Photo by Andrea Shreier.)

Sturgeons are notoriously stealthy, their journeys elusive. Miller’s mission was to implant fish with acoustic transmitters, which tracked them as they traveled throughout the watershed. She especially wanted to understand the migration and lifestyle differences between the Bay Area’s two resident species, green and white sturgeon, both of which are at risk from human activities.

“Sturgeon are the redwoods or the sequoias of San Francisco Bay,” says Levi Lewis, a migratory fish researcher at UC Davis. They’re big, old, and threatened—and, Lewis added, a part of California’s natural heritage and identity.

A UC Davis marine ecology PhD student at the time, Miller and her team ultimately tagged 201 fish. (She still goes by @sturgeonsurgeon on Twitter.) Surgically tagging individuals was a major undertaking, but finding out where they roam is crucial to protecting this ancient, iconic fish.

In the shallow waters of the bay, the net snared the sturgeon. This was the moment Miller had trained for.

Know your sturgeons

Sturgeons have been meandering along the world’s river bottoms for more than 200 million years, long before T. Rex roamed the land. Having hardly changed since, they’re often called “living fossils.”

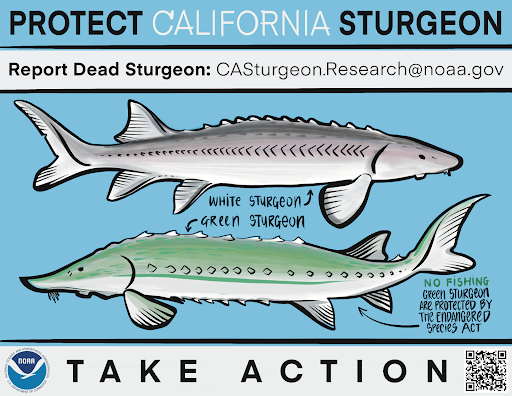

San Francisco Bay’s watershed is the only one on the West Coast where both green and white sturgeons spawn, according to Miller. Here’s how to distinguish our two local giants.

Green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) come in various shades of olive drab, with dark green stripes down their flanks. They can grow up to eight feet long and 350 pounds, with a lifespan of up to 60 years. California green sturgeon are listed as federally threatened.

White sturgeon (Acipenser transmontaneous) are North America’s largest freshwater fish. The most wizened individuals can grow up to 12 feet long and weigh 1,500 pounds, and they can live a century. White sturgeon are faring somewhat better than the greens, though the harmful algal bloom that took over San Francisco Bay waters in August 2022—the largest such bloom in the Bay’s history—may have put them in serious jeopardy.

Sturgeons, whatever the species, require clean water and plenty of reliable food to support their size, making them an indicator of overall watershed well-being.

“A healthy Bay has healthy sturgeon,” says Miller.

Minor sturgery

On bad days, Miller and her colleagues went without seeing a single sturgeon.

But this day was a good one. Their net brought up a perfect specimen—not too small for a safe surgery, and not too big to haul onto the boat’s deck.

The sturgeon thrashed its muscular tail. Miller lurched under the weight of its twisting body as she and her comrades hoisted it into their tagging cradle. Sturgeon resemble sharks in that they have mostly cartilage instead of bone, and smooth, rubbery skin coated in a slimy layer of mucus instead of scales. Their backs are studded with barbed, bony armor plates called scutes. Miller’s colleagues inspected the sturgeon for overall well-being and estimated its age. Rings on clippings from sturgeons’ bony pectoral fins can be counted, like tree rings, to age the fish.

Once the it was in the tagging cradle, Miller took the sturgeon’s measurements, pressing her forearms against the smooth, rubbery skin to calm it. The razor scutes studded across the sturgeon’s body sliced her surgical gloves and her wrists, but she focused through the sting on the task at hand. Miller gently rolled the fish onto its back so that it lay snug in the cradle, where it stopped wriggling. Pumped water sloshed over the fish’s gills. They would release the sturgeon back to the water as quickly as they could.

For months, Miller had practiced the surgery on foam rubber, dead fish, and even orange peels. Within about four minutes, she sterilized a patch of belly skin, sliced a two-to-three-centimeter incision, and slipped a chapstick-sized transmitter inside the sturgeon’s body. Then she stitched it back up with tidy, dissolvable sutures.

After such surgeries, Miller sometimes found herself gazing, for a brief moment, into the sturgeon’s bulbous, golden-ringed eyes. She marveled at its big, hooked scutes. They looked like diamonds, or stars.

“Up close, they really are dinosaurs,” says Miller.

With the help of her colleagues, Miller scooped the sturgeon out of the cradle and back onto its stomach. Then they lowered it out of the boat and back into the waters of San Pablo Bay. With a powerful thrash of its tail, the sturgeon disappeared.

Over the next six years, the transmitters that Miller and her colleagues at UC Davis implanted into 41 green and 160 white sturgeons pinged a unique code for each fish. The pings were heard, and recorded, by hundreds of receivers along bridges crossing the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and the Sacramento River, as well as buoys placed in the Bay and along the coast. For the first time, sturgeon researchers had detailed data from individual fish, young and old, green and white, gathered from across their migratory range. These pings gave scientists a glimpse into the big picture of how these fish use different habitats throughout the Bay.

Pacific traveler vs. stay-at-home sturgeon

The Bay’s two resident sturgeon species may look similar if you’re squinting through murky water, but they live very different lives.

Green sturgeon hatch in fresh water and spend their first three years as juveniles in the brackish Delta and North Bay. Then, like salmon, they embark on an epic saltwater journey. They head out along the Pacific coastline, commonly ranging from California to British Columbia. Every few years, they come back to the Bay, meandering into the Delta and rivers beyond to spawn in the spring and early summer. Some go as far up the Sacramento River as the Shasta Dam. Unlike salmon, adult green sturgeon survive the ordeal.

Tracking data from Miller’s surgically implanted transmitters showed that about 5 percent of migrating green sturgeon putzed around in the watershed after spawning for as long as a year. They hunkered down in deep holes along the Sacramento River—perhaps recovering their strength, according to Miller. Apart from these freshwater jaunts, green sturgeon spent most of their adult lives in the ocean.

White sturgeon, meanwhile, turned out to be relative homebodies. They migrated from the San Pablo and Suisun bays to spawn in the lower Sacramento River, and returned as soon as they were done. White sturgeon, it seems, spend most of their adulthood grazing along the clam beds in the muddy bottoms of these local bays.

Living fossils under threat

Bay Area sturgeons face many perils, in part due to bad luck: these prehistoric fish produce eggs humans prize as caviar. In the 1860s, the Bay’s white sturgeon were nearly wiped out by overfishing. Commercial fishing was banned in 1917. Size restrictions on recreational fishing came later, to spare juveniles and the largest fish, which make the most eggs.

In response, the caviar trade went underground. Now poached caviar, sometimes called “black gold,” can sell for $150 per pound on the black market, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Meanwhile, sturgeon caviar sold by legal farm operations in the Central Valley can fetch about $100 per ounce, as the East Bay Times reported this year. During a traffic stop in 2021, officers found a seven-foot sturgeon in the back of a suspected poacher’s pickup truck. (The fish was barely alive, and officers rushed to release it into the water, after photographing it for evidence.) In 2022, CDFW officers charged eight people for allegedly poaching at least 36 white sturgeon in Sacramento Valley waterways.

Both sturgeon species are threatened by harmful algal blooms, habitat fragmentation, ship strikes, sea lion predation, selenium pollution from oil refineries, and waterway alterations such as levees and dams. Green sturgeon are illegal to catch due to their threatened status, but they are particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation. Dams block sturgeon on their way to spawn, and busy ship traffic in the Golden Gate Strait disrupts their journeys.

Tagging studies like Miller’s continue to help government agencies and managers know which parts of the San Francisco Bay watershed are most crucial to sturgeon spawning and survival, and therefore most essential to conserve. But so much remains unknown, including how many sturgeon are out there. Even with tagging studies and annual CDFW monitoring surveys, these fishes’ stealth and wide range makes counting them a monumental task. For now, most sturgeon go uncounted, and the causes of their deaths often remain a mystery.

“Our tags eventually die, before the fish dies,” says Miller.

This summer’s harmful algal bloom dealt a major blow to homebody white sturgeon, with repercussions that will be felt in the slow-to-reproduce population for decades to come. According to Lewis, the UC Davis fish researcher, humans will likely need to intervene in order to protect these living fossils while they still glide along the bottom of the Bay, unseen but not unaffected by human activities above.

“If we can reduce the amount of unnatural mortality,” he says, “that will give them the best fighting chance to survive in this rapidly changing world that we’re living in.”