Restoration ecologists in the Presidio of San Francisco recently removed a small stand of 100-year-old trees to expose an ecosystem that exists in only a few places along the California coast.

It’s called coastal dune scrub and beginning this winter, San Franciscans will have the opportunity to watch it return and meet the plants and insects that for millennia have called the hills above Baker Beach their home.

Many people feel at home among the eucalyptus and Monterey pine trees that were widely planted throughout the Presidio in the 1880s, and they’ve come to expect the towering non-natives as they walk through the national park. The Presidio has taken the initiative to replace many of the aging forests with younger, healthier trees to protect the cultural legacy of the park. But in this instance, restoration ecologists see value in substituting trees with a native habitat type that can exist in only a handful of places along the coast.

“Many people don’t even know what a coastal scrub is, or what coastal dunes look like,” said Jack Dumbacher, the California Academy of Science’s curator and department chair of ornithology and mammalogy. “If they had seen what the habitat looked like 150 years ago, they’d probably love it a lot more.”

Drying out a Pacific Northwest

San Francisco used to be a short-statured landscape, kept that way by the strength of winter storms and summer winds. The landscape remained dry and sandy since the shorter plants weren’t tall enough to catch the moisture-filled fog streaming in off the Pacific. The shorter plants also allowed for plenty of sunlight and open space for multiple species to thrive. The European settlers with their East Coast garden ideals changed that.

“We turned this very unique province basically into the Pacific Northwest,” said Dan Gluesenkamp, executive director of the California Native Plant Society. “It became much, much wetter. That’s a fundamental transformation. Those San Francisco plants that evolved with a long and ancient history of wind have a hard time living under a Monterey pine that’s dropping a ton of mulch and [through fog drip] has increased rainfall tenfold.”

The trees also blocked sunlight, changed the chemistry of the soil, and stabilized an environment where native plants had needed the flexibility of shifting dunes to grow. Put bluntly, for the dunes above Baker Beach to return with a healthy variety of native plants, insects, and birds —the trees have to go.

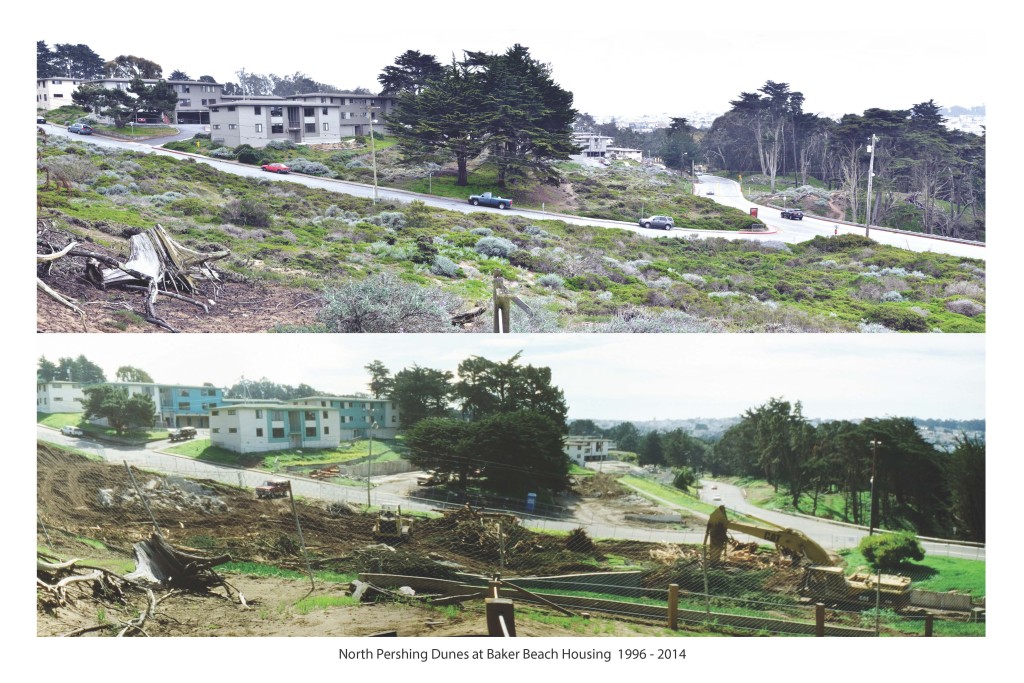

In October, under the supervision of Presidio Trust restoration ecologist Lew Stringer, the pines were cut and the stumps ground out. Over the next months, pine duff will be removed and the soil turned so that oils and waxes that had dripped from the trees for decades will be buried. If left on the surface, they create slick, impermeable areas where water pools, causing soil erosion.

Presidio Park Stewards, a drop-in volunteer program organized by the Presidio Trust, along with Presidio interns and staff ecologists, will sculpt the soil to look as natural as possible. Then they will seed it with stock that’s been collected from within the Presidio and prepared at the Presidio Nursery. It will take careful monitoring and diligence to stomp out invasive species that creep in before the seedlings establish themselves.

Then the fun will begin.

Come next spring, the golden orange of California poppies, deep blues of miniature lupines, and bright yellows of the sandysoil suncup will splash across the hillside. There will be rattlesnake weed, popcorn flower, and blue toadflax all in bloom, beckoning pollinators to visit.

“Restoring dune ecosystems is a guarantee to bring vitality back to the area,” says San Francisco lepidopterist and conservationist Liam O’Brien. “I mean seriously, just add water and stir. It’s kind of an amazing thing to watch.”

Thinking small about big predators

The vitality will start with the insects that arrive first, like the green hairstreak butterfly, which resembles a kind of small jewel with its iridescent green underside. Populations of green hairstreak live nearby in the Lobos dunes and coastal bluffs, meaning the species will have an easier chance of naturally expanding into the restored habitat. The butterflies serve a unique purpose.

“They’re not pollinators. That’s a horrible misconception,” said O’Brien. “I guarantee you’ll look at a butterfly’s leg on a flower and never see pollen. What they are is a smorgasbord for everyone else.”

According to O’Brien, 90 percent of all butterfly eggs are eaten by other insects and birds. Wasps and larvae parasitize 80 to 90 percent of all caterpillars and pupa. Then at the adult stage, the beautiful butterfly phase, birds eat 80 percent of those. Butterflies are food.

The robber fly often waits around flowers and snatches whatever insects come to feed on the nectar, including butterflies.

“It’s as interesting as a tiger or a lion, but on a more micro scale,” said John Hafernik, professor of biology at San Francisco State University and president of the California Academy of Sciences.

Wasps and bees will also begin nesting in burrows in the open sandy areas, stalking their insect prey. In the open sand patches interspersed among the scrub plants, a thread-waisted wasp might be found digging a hole in the sand, carrying a caterpillar that it has stung and paralyzed to bury and lay an egg on.

“You can see a lot of the dynamics of the natural world if you just stop a little bit, be a careful observer, and think a little bit small rather than big in what you’re looking for,” said Hafernik.

Creating a native legacy

It’s a good era for dune scrub restoration, said Gluesenkamp. Projects large and small are happening around Northern California, from sites along Humboldt Bay to Tom’s Point on Tomales Bay. People are energized to save rare habitats and species, he said.

“We have a community of folks out there who get it, who are really falling in love with California nature and not trying to make it something else,” said Gluesenkamp. “They love the distinctiveness and are willing to support these projects either by going out and volunteering, as you get in a place like San Francisco, or just understanding and supporting ambitious things.”

One of the success stories of the ongoing native plant restoration is the San Francisco lessingia, which as a federally listed endangered species was down to a mere nine individuals due to habitat decline. Presidio restoration ecologists responded by rebuilding sand dunes over an old army ball field in the southwest corner of the Presidio, in an area called Lobos Valley. They seeded the restored dunes and six years later, the species has rebounded to more than two million individuals. Visitors can now stroll a boardwalk through Lobos Valley and be surrounded by the deep yellow flowering plant when it blooms July through October.

As for the restoration above Baker Beach, there will be many opportunities through the Presidio Park Stewards program for volunteers to get their hands dirty, planting, weeding, and caring for and learning about the nascent plant and insect communities.

Following the initial eyesore of felled trees, life will return, more abundant, and more historically suited for the sweeping hills that spill to San Francisco’s bluffs.

“For us to appreciate these things that are rare and fleeting and hard to protect, you need to have them and experience them, to grow up with them and learn to love them,” said Dumbacher.

Without restoration projects like these, that opportunity to love what’s local could be lost on generations to come.