This spring, caught between waves of despair and disgust at the world outside, I turned for solace to my garden—but not entirely for gardening. No, betwixt the lettuces and heads of kale, I retreated into an entomologist cult classic: the training of flies in the genus Coenosia to rest on my hand, launch after flying prey, and return like wrathful half-centimeter orange-eyed raptors, a fresh catch impaled on their medievally spiked mouthparts.

It is magical, almost unbelievable, how easy it is to persuade one of these flies to climb onto your hand. Find a fly and put your finger directly in front of it. Slide your finger forward until you’re touching the fly; it will just clamber right up. From there you can walk around as any falconer might, perhaps humming Die Walküre. When it is ready, your fly will swoop off, hunting. It will use piercing mouthparts to skewer its catch midair, then land again to consume it—with luck, on your finger, though mine always chose somewhere else nearby.

I first noticed these flies around mid-February, perched atop overgrown radish greens. Their boldness stood out as I loomed with a macro lens, at which point I also noticed the prey they often clutched beneath them. Curious, I did some research and learned about the finger trick just as COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders arrived. From then on, flies became my most physically proximate colleagues.

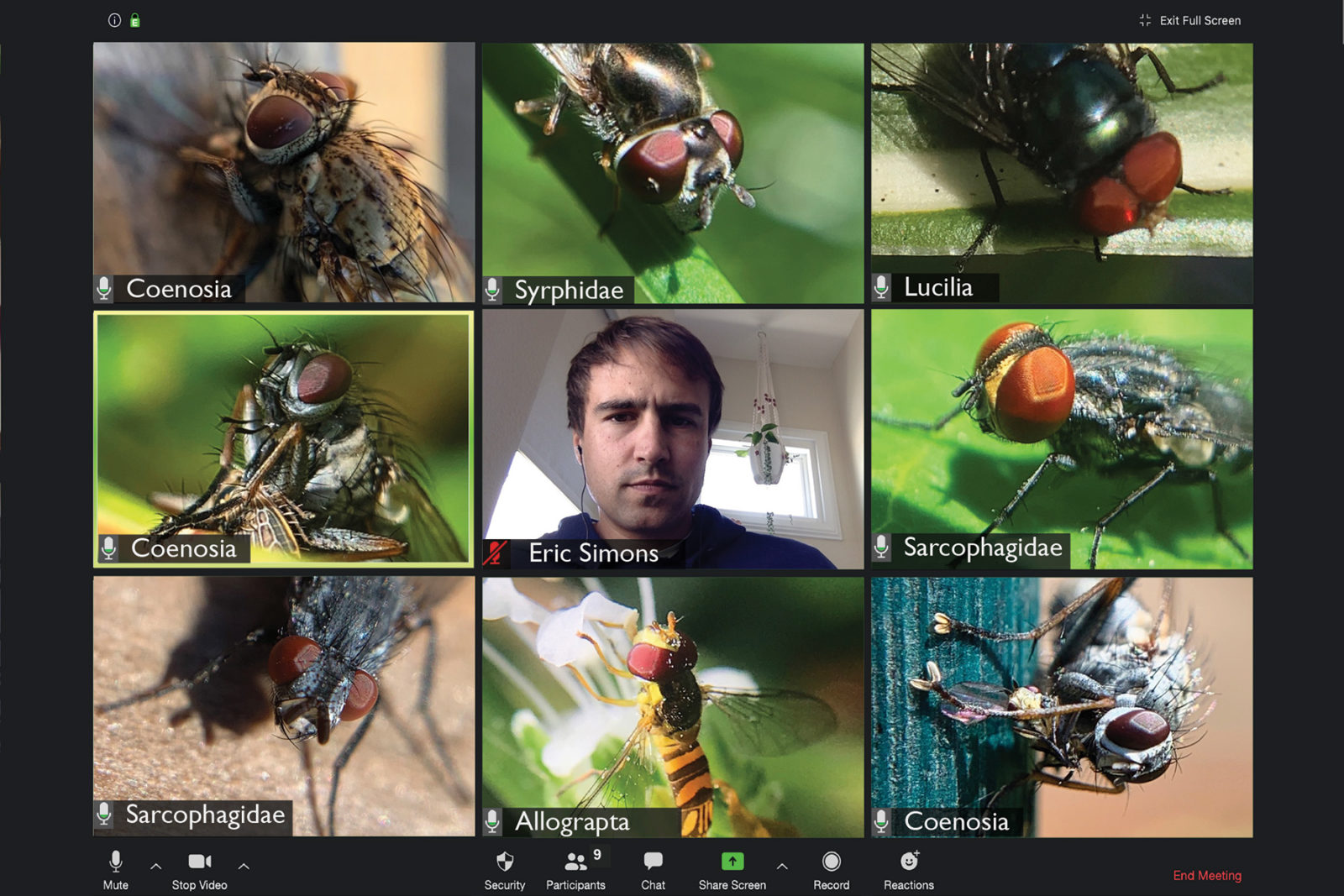

Any time you meet a lot of new co-workers, it takes a while to put names to faces. This is even more complicated when it comes to putting names to flies. (And I don’t mean Flychael Jackson or Coronaflyrus, as a fellow editor at Bay Nature suggested.) Flies account for about one in ten species on earth, according to Michelle Trautwein, an entomologist at the California Academy of Sciences. There are more than 150,000 described species of fly and potentially millions of species yet to discover. Many flies look alike but still meet the definition of a distinct species: an inability to reproduce with each other and have fertile offspring. This diversity is partly because flies have what researchers call “lock and key” genitalia, and male flies, it turns out, have a variety of keys unsuited to our prudish human vocabulary. Since you often can’t identify a fly conclusively without looking at its key under a microscope, experts tend not to bother.

I showed two of those experts, California Department of Food and Agriculture entomologists Steve Gaimari and Martin Hauser, a picture of my backyard fly. They confirmed it was in the genus Coenosia, nicknamed “tiger” or “killer” flies. I asked how you’d be sure, when it appeared to me similar to other flies—like, for example, the Sarcophagids, which are also smallish grayish striped-ish backyard flies that loiter on my garden plants. There was a long pause as they searched for a diplomatic answer.

“They look as similar as a fish to a mouse to us,” Hauser said. “But as an expert, you look at the overall gestalt.” In the absence of a microscope and a look at the male genitalia, Hauser and Gaimari agreed, you’d look at size, shape, stance, and facial details like palp length. Coenosia flies have long legs, long palps, a bit of a hunch, and a lighter-shaded body than many other houseflies. They are characteristically bold, and both larvae and adults are predators. They are also more studied than most flies because of their usefulness as agents of biocontrol—especially in greenhouses, where they turn their talents to hunting down aphids, whiteflies, and other garden pests.

Hauser shared with me an 83-page dissertation on Coenosia, written in 1997 by a German dipterologist. (It was entirely in German, but Hauser guessed—correctly—that I’d enjoy the pictures.) It was a revelation to realize that backyard flies that will climb onto your finger and claim aerial superiority over your lawn, flies that six months ago I had no idea even existed, are among the most understood flies. In a world made smaller by shelter-in-place orders, I found a kind of renewing delight in their existence among my radishes. They imply such endless mysteries flying constantly through even our diminished worlds.

“We get this question a lot when we’re out in the field, running around,” Hauser said. “People say, are you catching birds? Are you catching butterflies?’

We say, ‘No. We are catching flies.’

They say, ‘Why do you catch flies?’

We say, ‘Why don’t you catch flies?’

They’re the most amazing things in the universe.”