Deep within a coast redwood grove, we’re slowly approaching the McApin Tree. With countless decades of accumulated duff underfoot and no established trails or footpaths to follow, we proceed carefully to sidestep delicate trilliums and the leafy sword and bracken ferns. I’m watching my step and admiring the scattered light around my feet when I look up and see it towering before me. From its buttressed, knotty base, the heavily grooved McApin Tree rises into the canopy far beyond our range of sight. Its lowest limbs, draped with hanging mosses, are easily more than 70 feet above my head.

The tree spreads and soars into the forest canopy, and I’m told that at nearly 20 feet across and 239 feet tall it rivals the famed ancient redwoods farther north in California. But we’re a long way south of those giants, hiking through northwestern Sonoma County, where the McApin Tree is the oldest known living redwood south of Mendocino County. Few have seen the tree, which has been shrouded in forest on private property for more than a century. There were rumors about the trees here, of course. But it wasn’t until this year that Save the Redwoods League scientists took five core samples from the McApin Tree and determined that it’s 1,640 years old.

The behemoth balances on a slight slope, with bay laurels and Douglas firs growing in its shade. Needles and leaves layer the ground, and I crunch cautiously, unsure of the firmness and grade, as I make my way around the tree’s stately trunk. In places, cobwebs fill what seems like every groove in the spongy bark. A few chunky burls packed with dormant buds pad the base, ready to sprout a lineage.

The mammoth tree is not only the venerable elder in this grove. It’s thought the McApin Tree holds within its fire-charred rings the surrounding forest’s formative secrets.

In the 1870s, Herbert Archer “H.A.” Richardson came to California from New Hampshire and began acquiring what would eventually total 50,000 acres of forestland in western Sonoma County. Much of it supported centuries-old redwood trees that crowded valleys and gave shelter to mountain lions and deer, voles and squirrels, salamanders and banana slugs, and dozens of bird species. The occasional California grizzly bear still roamed the region. Creeks and rivers laced the land and swelled with salmon during their annual runs. Much of the area, including eight miles of coastline, eventually became Richardson’s property. At one point, he even owned the entire small town of Stewarts Point.

At the same time Richardson was buying land, San Francisco’s population was ballooning in the wake of the Gold Rush, and most of the city’s construction relied on redwood mills from the northernmost parts of the state. Coast redwood forests covered some 2.2 million acres, stretching from southernmost Oregon to Big Sur, and the mills were processing redwoods and their inland giant sequoia cousins at breakneck speed. But a swath of trees near the North Pacific Coast Railroad terminus in Cazadero—despite the boom times and taxes on owners who left tall trees standing—went largely untouched.

The statewide destruction of forests led to a heady era for redwoods conservationists. During the mid- to late 1800s, a few park preservation acts set aside what would become Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. In 1905, California passed a Forest Protection Act; Big Basin Redwoods State Park and Muir Woods National Monument followed as cornerstones in California’s state park system and the national park system. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act, thereby creating the National Park Service.

In 1917 influential lawyer Madison Grant, American Museum of Natural History president Henry Fairfield Osborn, and UC Berkeley paleontology professor John C. Merriam took a road trip north to Humboldt and Del Norte counties to see the giant trees building the cities. Awed by the groves of colossal trees, they found what local leaders, particularly the Humboldt County Federation of Women’s Clubs, had been saying for years: The redwoods are a California treasure and are falling too fast. Save the Redwoods League was formed to try and prevent further loss. Within its first years, the League partnered with burgeoning federal and state agencies to help establish California’s state park system in 1927. In the 100 years since its own founding, the League has contributed to protecting 214,000 acres of redwoods in California and helped to create 66 redwood parks and reserves for the public.

All the while, the trees near Cazadero continued to grow taller, including the matriarchal McApin Tree.

The small group assembled next to a rural two-lane road was keen to get into the lush forest. But before loading into all-terrain buggies and heading to the storied trees, we heard from Dan Falk, a fifth-generation member of the Richardson family. Falk is the grandnephew of the late Harold Richardson, grandson of H.A. Richardson. Falk runs a regional timber business—one mill is visible from where we stand—and is excited to tell us about the 730-acre property the family has owned since the 1920s that holds the McApin Tree.

For the better part of a century, he explains, few had even seen photos of the Richardsons’ redwood forest. The family took the highest degree of care to conserve this plot of land for the simple reason that they enjoyed going there for picnics and get-togethers. That tendency toward conservation led to a partnership with Save the Redwoods League, which was eager to help the family protect but also share this ancient forest. “The Richardsons didn’t shout ‘Look what good stewards we’re being,’” notes Sam Hodder, League president and . “They cared for this place because it is special. It’s the very best of what’s left of the old-growth forests.”

Explore coast redwoods or giant sequoia anywhere in California and Oregon with the Save the Redwoods League’s new mobile-friendly web tool for a comprehensive list of parks, planning tips, and new ideas: ExploreRedwoods.org

The Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve protects the most old-growth coast redwood forest standing on private land anywhere today, and it looks much as it did in the 1870s. Many of the trees reach higher than 250 feet—the tallest is 322 feet—and they make up part of the remaining 5 percent of ancient coast redwood forests in the world. By definition, old-growth forests are relatively untouched by humans, with layers of canopy and many downed trees that provide habitat over centuries; the tannin within the wood prevents decay. The forest floor is a deep web of fallen logs partially or entirely buried beneath a surface of duff, new soil, and the roots of the next generation of giants. They provide refuge to species of concern like Townsend’s big-eared bats as well as threatened species like northern spotted owls and marbled murrelets. Today, coast redwoods occupy parts of a slim 35-mile-wide, 450-mile-long stretch just inland from the Pacific Ocean, or about 113,000 acres in the entire state.

In June, after decades of building a relationship and several years of quiet discussions, the League finalized its purchase of the property from the Richardson family. The League named it the Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve after the late family patriarch who did in fact steward this impressive forest. For a few years the League will provide docent-led tours of the reserve and then will open the reserve to the general public. When that happens, it will be the first new old-growth redwood park opened to the public in California in a very long time, offering “tremendous opportunity for the redwood forest to continue on its trajectory to inspire the world,” Hodder says.

The League will also manage the reserve, a significant change for an organization that has historically purchased land and transferred it for care to government agencies such as California state parks. But as publicly funded entities are increasingly unable to take on new properties due to lack of funding and political support, the League has decided to also undertake management. Slowly the League has learned to augment the work of other agencies, Hodder says. “We’re managing and restoring, we’re placing culverts, building trails, and getting ready for the public,” he enthuses.

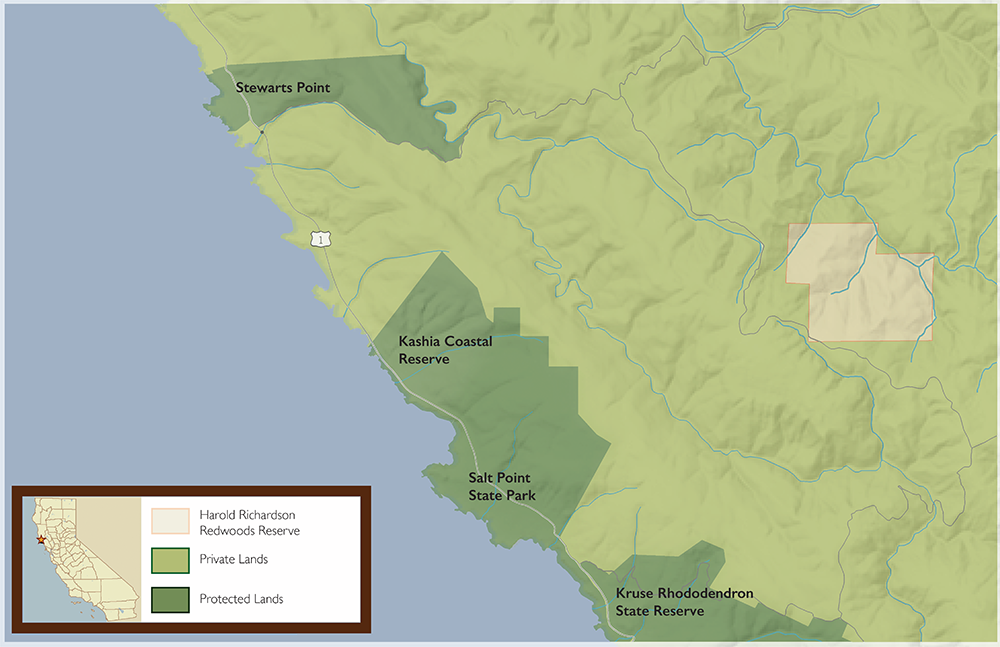

As part of the League’s purchase of Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve, the organization and the Richardson family will exchange an 870-acre protected coastal property at nearby Stewarts Point. The League purchased the Stewarts Point property from another branch of the Richardson family back in 2010 and has negotiated three easements that will conserve the property and its uses in perpetuity. The conservation easement, which includes protection of 175 acres of young and old-growth coast redwoods along the Gualala River as a restoration reserve, is held by the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District and was funded by the district, the Wildlife Conservation Board, and the California State Coastal Conservancy. Another 525 acres can be used for sustainable logging of second-growth redwoods, Douglas fir, and bishop pine guided by the conservation easement’s requirements for additional ecological protection. A trail easement along the property’s coastal bluff allows for the expansion of the California Coastal Trail, which Sonoma County Regional Parks will build and manage by the end of 2019. And a cultural access easement will enable the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians to access their ancestral home.

It’s a unique partnership at a unique time. The land trade is a creative solution to match fundraising efforts to purchase the reserve. It comes as the organization celebrates its centennial with one eye on the past and one toward the future. Since the organization was founded in 1918, the League’s original mission—to protect the ancient redwood forest through land acquisition and support the parks system that stewards them—remains largely unchanged. But now that the state’s remaining old-growth redwoods are, for the most part, either harvested or protected, the League’s vision is expanding toward purchasing and restoring second-growth redwoods, so that they might become the old-growth forests of the future. “We have a reputation as an organization that focuses on old-growth forests, and indeed, that has been a big part of our work during our first century,” Hodder says. “What is not as well known and understood is our work with younger forests.”

Protecting Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve helps ensure that generations of families and visitors will enjoy the unspoiled land, and it’s clear as I circle the wide base of its oldest tree that this parcel is a thriving, manifold ecosystem that has benefited from being largely untouched. From near the McApin Tree’s bumpy trunk, Catherine Elliott, the League’s senior manager of land protection, scoops up an owl pellet the size of a toddler’s fist and explains that it is likely from a great horned owl that lives in one of the tree’s many deep crevices. “Last time I was here, it flew right out at us when we approached,” she says to us, hoping we’ll catch another glimpse of the evasive bird of prey. (No such luck.)

League scientists maintain that the McApin Tree holds this land’s oldest stories within its dense rings, which seem to have withstood numerous blazes that took down nearly every other tree in the area. The rest of its redwoods are much younger, dating back between 500 and 800 years. “From a forest ecology standpoint, something happened on this property that we’re really excited to learn about,” Hodder says. “There was some sort of event that made the forest start from scratch again, leaving these monarchs of a new generation.”

Collecting and studying tree ring data and core samples—work already well under way—could help tree ecologists determine what mysterious event felled most of the forest, perhaps something related to the nearby San Andreas Fault. Hodder adds that what is revealed of this history will likely inform the League’s stewardship of the reserve.

Stories about the oldest redwood forests have always had a mythic quality. Redwoods researchers funded by the League once discovered a species of salamander that may live its entire life in the canopy. Another time, a team found a mature Douglas fir growing high off the ground in the redwood forest canopy.

There’s still much to discover. Just in the realm of epiphytes—which includes lichen, mosses, and ferns—new species have been identified among the hundreds of species living in redwood canopies, a complex area of research the League has funded. A recent examination of canopies in Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve, slightly east of Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve, found 217 species of epiphytes, including a new lichen dubbed Xylopsora canopeorum; the Greek and Latin translate to “wood carpet of the canopy.” Researchers also documented a greater diversity of lichen species in redwood canopies within the tree’s southern range, such as the Bay Area, than in the northern range, perhaps due to the lower moisture levels. Too, the older the redwood, the more diverse the epiphyte community it hosts. To continue restoring second-growth forests and cultivating their healthiest aspects, League scientists need to understand the role of epiphytes in redwood forest ecology. For example, the tannins in redwoods prevent most creatures, be they burrowing insects or browsing deer, from eating any part of the tree. As a result, redwood forest dwellers may depend on epiphytes as food.

The ferns that live on and near redwoods are also powerful barometers of forest health. Since 2012, Dr. Emily Burns, the League’s director of science, has been leading the crowd-sourced Fern Watch, a project that relies in part on photographs of ferns uploaded to the iNaturalist app by citizen scientists, covering a range of 120 plots from Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park near Crescent City to Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve near Big Sur. With so much ground to cover, Burns and her team rely on these field reports to best plan future health checks, and if needed, to gather additional data.

Monitoring fern health during drought years, when ferns shrink and have fewer and shorter fronds, has been especially vital work. Ferns’ shallow roots are highly sensitive to the signals of drought. By measuring the size of the fronds, experts can detect whether enough water has come into the forest to support vigorous growth. Ferns with small fronds conserve more water. Ferns that can survive these temporary setbacks offer insight into how hardy redwood forests adapt to and rebound from extreme drought conditions.

In 2012 and 2013, Burns’ team noticed that Western sword ferns endured the drought by reducing their leaf area by about one third. The bigger the fern, the more water it loses. For scientists, that simple relationship is an approachable way to introduce practically anyone to indicators of forest health and help the public get more involved with efforts to track resiliency. “With the rains returning last year and this year, we’re hoping we’ll see ferns literally expand again and have larger populations,” Burns adds.

Western sword ferns are but one species League scientists are eager to study at Harold Richardson Redwoods Reserve. Foresters have also found evidence here of the presence of red tree voles. These tiny, nocturnal rodents are no more than eight inches long and weigh a mere two ounces (at most) with their long, fur-covered tails accounting for more than half their body length. Being among the few animals that can thrive on a primary diet of conifer needles, they often live in and subsist on the needles of a single Douglas fir their entire lives. Though elusive, they leave easily identifiable signs: discarded resin ducts from the needles they gnaw often pile up at the base of the firs they inhabit.

This remarkable complexity of redwood forest ecology exists for a decidedly unexciting reason: Redwood forests are an incredibly stable habitat. Redwood trees are enormous carbon sinks, and their forests are able to store more than three times as much carbon per acre than any other type of forest in the world, including the Amazon rainforest. Individual redwoods can add more than 2,000 pounds of wood annually. The older and larger the tree, the more wood it puts on each year.

This stability also means that coast redwoods are a refuge of resilience and forest health as climate change continues. An old-growth forest’s adaptation to extreme weather events, such as redwood trees retaining enough water to withstand drought over many years, is reason for optimism, Hodder maintains. “During our generation’s tenure as stewards of these forests, we have learned of both the critical challenge of climate change and the critical role of the redwoods in the fight against it. We have in these forests an extraordinary opportunity to restore resilience into the ecosystem, if we are willing to make different choices in how we steward them,” he says.

As the League looks ahead, stewardship and climate change are at the forefront of the organization’s vision. In its next 100 years, the League wants to double the acreage of forests in reserves and protect existing old-growth redwood forests from any further development. It will also increasingly focus on second-growth redwoods and restoring their health. This is a significant change for the organization. “Forest stewardship is as critical as protecting the land,” Burns explains, “and I hope we continue to inspire people to invest in scientific projects.”

Among those projects is the League’s Redwood Genome Project, a five-year undertaking begun in 2017. Other conifer genomes, including the Douglas fir and sugar pine, have recently been sequenced. But the massive size of the coast redwood genome, which is 10 times larger than the human genome, has posed particular challenges. In addition, coast redwoods have six sets of large chromosomes (humans have only two). In the last decade, the technology has improved and the price has plummeted enough to tackle such a computationally difficult sequencing project. Burns oversees the project partnership, which also includes researchers from the University of California, Davis, and Johns Hopkins University; scientists anticipate the coast redwood genome sequence will be completed later this year.

The genome will ultimately allow identification of the most genetically diverse coast redwood forests to help ensure they’re protected. It can also help scientists ascertain if a second-growth forest has low genetic diversity and strive to prevent any further loss. Burns describes genetic diversity of the entire coast redwood population as “the raw material that will help this species adapt to environmental changes.” That’s the idea, but at this early stage researchers will genotype individual trees to answer specific management questions. For instance, it’s common practice in some parts of the redwoods range to plant clones from a handful of genotypes, and it’s not yet clear whether the monocultures created by this type of planting are unhealthy. Burns notes that the ability to identify trees that are specifically well adapted to particular regions can offer a guidepost for future forest management. “This could also inform where to conserve lands, to ensure that forests with unique genotypes are protected,” she says.

Reports on the history of coast redwoods invariably—and with good reason—include how much acreage has been lost in the past century. In 2013, the coast redwood was named as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. But to hike in the presence of the Bay Area’s biggest trees, some over 300 feet tall, is to feel like we have a lot to gain. Standing next to the McApin Tree, struggling to imagine 16 centuries of existence, I reflect on how lucky we are to have the coast redwood forests grow among us. Unlike glacial and tropical ecosystems that are crucial to protect for planetary health but seem very far away, coast redwoods are part of our community. They literally house millions of people in California. They grow along our sidewalks and populate neighborhood parks. They’re where we take our out-of-town visitors and the place we get away to for a weekend of camping. We can lay our hands on these species that need saving.

And it’s worth noting we already have preserved a lot, thanks to the enthusiastic support of the public and land stewards like the Richardson family. Hodder says that redwood restoration continues to be a story of hope. “So much of the conservation conversation is about anxiety, degradation, and losing momentum,” he says. “But for all the hand-wringing about the old growth we have lost, it is incredible to realize so much of what we have preserved and continue to cultivate is still redwood forest. Some of it just happens to be young!”

Imagine what it’ll be in a redwood-quick century.