The big day is here. The sun hasn’t broken through the morning chill yet, and a pack of experts is giving me the lay of the land — a dewy, grassy expanse where the stakes are incredibly high. I count myself lucky to be here to witness firsthand what so many have only seen on their TV or computer screens: the Superb Owl.

Oh, right, there’s another way to arrange those letters that’s culturally relevant. Fine, Sunday’s a sports day, but spare a thought for the owls, because I think we can universally agree that owls are really flipping cool. The swooping down on prey, the preternatural night vision and unique hearing abilities… the talons! It’s enough to make this Washington State girl forget about the majestic seahawk (aka osprey) completely.

So with the sportsball in mind, I asked a few bird experts to find me those owls. They brought me to San Jose, to the region’s only actual dedicated “owl preserve,” a nameless plot of land not normally open to the public.

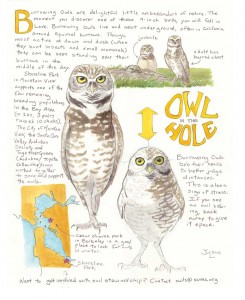

The owl in residence is the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), the experts say, which we’ll find during the day sticking close to burrows, protecting homes and potentially their mates.

Standing at the dead end of Nortech Parkway in north San Jose, inside the padlocked fence, we see their burrows: big mounds of dirt a couple feet high popping up amidst short grass. This short grass enables burrowing owls to see their prey, which includes small rodents but also quite a few insects. That’s some crickets and grasshoppers, but mostly earwigs.

Binoculars hanging around their necks, and one absurdly large telephoto lens at hand, the experts guide me on a walk through the 180-acre owl preserve that was established when San Jose’s City Council adopted a plan for its aging wastewater facility that also covered uses of the surrounding lands. (The Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society helps manage the preserve with a grant from the city of San Jose.)

During my tour, we have Philip Higgins, a biologist who helps monitor Santa Clara Valley burrowing owl habitats, and Joshua McCluskey, who manages the burrowing owl conservation project at the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society.

Rounding out the panel is Ken Davies, whose expertise is at the municipal government level. He’s an environmental compliance officer for the city of San Jose, and he’s here to tell me how the city has been active in preserving this land for the owls.

All right, I think, but the proof is in the owl pudding. (I assume owl pudding is cricket and earwig based, but I didn’t get a chance to ask.) Anyway. Show me the owls!

We set off to the northwest and come across a pile of hay bales, which is meant to foster rodent life for the owls to feed off of. Higgins tips a bale over to reveal a mouse track and a wealth of members of the Armadillidium family, otherwise known as the roly poly or the pill bug.

We approach a rise in the distance and I try to absorb owl expertise whilst keeping my eyes peeled. I point amateurishly off to the east. “There! I think I see one!!” A graceful bird circles close to the ground in the far distance, but I’m the only one who can see it. No, McCluskey says, a burrowing owl wouldn’t be flying around during the daytime. He and Higgins list off all the varieties of hawk and eagle that inhabit the area.

That might have been the western harrier they saw earlier in the morning. Or a peregrine falcon or a golden eagle, both owl predators.

We pass by a pile of wood and other brush covered in streaky white evidence of owls: poop. The brush pile, too, is meant to encourage rodents.

One kind of rodent isn’t normally prey, but is exceptionally important to the owls: ground squirrels. Higgins tells me about the relationship between the species, and frankly, it sounds rather one-sided. The owls don’t dig burrows to live in; the squirrels do that, but once they leave, the owls move in and nest there.

Unlike rodents, owls are not fastidiously neat, and they cover the burrows with white leavings and sometimes “decoration,” as Higgins describes it. This includes shiny things like foil, but also goose poop and other garbage. Higgins once saw a cheese sandwich at the entrance to a burrow.

Once the owls move out, the squirrels move back in and make things tidy again. Other than heeding the owl’s warning calls for predators, which include foxes, house cats, opossums and raccoons in addition to the raptors and eagles, the squirrels don’t get much out of the deal.

Interspecies politics aside, the owls need the squirrels, and so the city of San Jose has tried to make the sanctuary appealing to them. That’s meant putting in more than 80,000 cubic yards of loose soil to promote burrowing, Davies says, and a bit of manipulation. The squirrel population started off in the northwest corner, so every year they plan to keep moving the soil deliveries further into the interior of the sanctuary hoping the squirrels will follow.

As I write, Phil says “There it is!” Then, “No, but that’s a western meadowlark.” A group of medium sized not-owls takes flight from the other side of the rise. I glumly take a photo of them lifting off the ground together.

Well, I might not see any owls today, I think. I look desperately up and snap a shot of a plane ascending (I don’t know, because it flies?), and then settle in to hearing more about the owls from Higgins. He shows me an owl pellet filled with earwig antenna.

Foolishly writing things down in my notebook, I jerk up to hear, “There’s one!” The experts are standing expertly with their binoculars, pointing it out to each other by naming the particular burrow the bird is standing to the right of.

“He’s already on guard,” McCluskey says. “He or she.”

My camera lens’s 250-millimeter zoom is insufficient to get a good look, so McCluskey lends me his binoculars. I own binoculars but somehow neglected to bring this birding essential. I imagine this is something like forgetting the guacamole at your Super Bowl party.

The owl is dun in color and mottled with white spots, looking like a light colored stone on long legs. It’s motionless, guarding, waiting. When approached, they typically bob up and down and call out a warning cry to other owls, according to one U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report. I don’t get close enough to see for myself.

Then we’re just knee deep in owls. We unsuspectingly approach burrow 1 and an owl flushes from the mound, flying toward burrow 2. We get closer and another owl flushes from burrow 1 to burrow 2. A pair. The owls are approaching mating season and these two appear to be together.

Oh, wait, what’s that? Another pair is hunched down together at a burrow right next door to burrow 2. They’re still incredibly far away, but I can see the well-camouflaged birds side by side, making sure we don’t threaten their burrow.

Now, you, fellow superb owl-admirer, will also have a hard time seeing these birds up close in the feathery flesh should you seek them out.

It’s true that burrowing owls are great for viewing during the daytime, more so than the other more nocturnal owl species. And the camera traps set up at the sanctuary prove that the owls are full of foibles and hijinks, McCluskey said. They fight among each other over crickets and mice and get their feathers ruffled.

(During one chick count, Higgins got very close to a group of three chicks who panicked and forgot where their burrow opening was. One of the youngsters — “no feathers, all fluff” — puffed up, flapped its tiny wings and screeched. It charged Higgins, only to fall on its face. In a word, McCluskey said, the birds are “dorky.”)

State law prohibits lay people from getting too close to owls during breeding season. If an owl reacts by flushing, “It messes with the calorie balance,” McCluskey says. “You could imperil the bird.”

Burrowing owls are birds of conservation concern according to the USFWS, and a state species of special concern. In the San Francisco Bay Area, they are in a precipitous decline.

Loss of habitat is the biggest obstacle to keeping the burrowing owl going strong in the region. But the owl species is thriving here on this field; Higgins said all of the pairs successfully bred last year, compared to the 50 percent success rate he’s calculated for all of the owl habitats he observes in the Santa Clara Valley.

Out of the seven sites Higgins originally studied in the area, only three have any owls left in addition to this one: the San Jose International Airport, Shoreline at Mountain View and Moffett Field.

McCluskey says they would like the birds, which the researchers have just started banding, to spread as far as Coyote Valley, at the southern end of San Jose where another area rich in wildlife diversity and open spaces straddles Highway 101.

That would require the preserve here to overflow with owls, which would be a win for the superb owl and all its fans.

Find out more about the City of San Jose’s owl preserve, or check out the city’s Flickr page with photos from the camera traps.