Know before you go

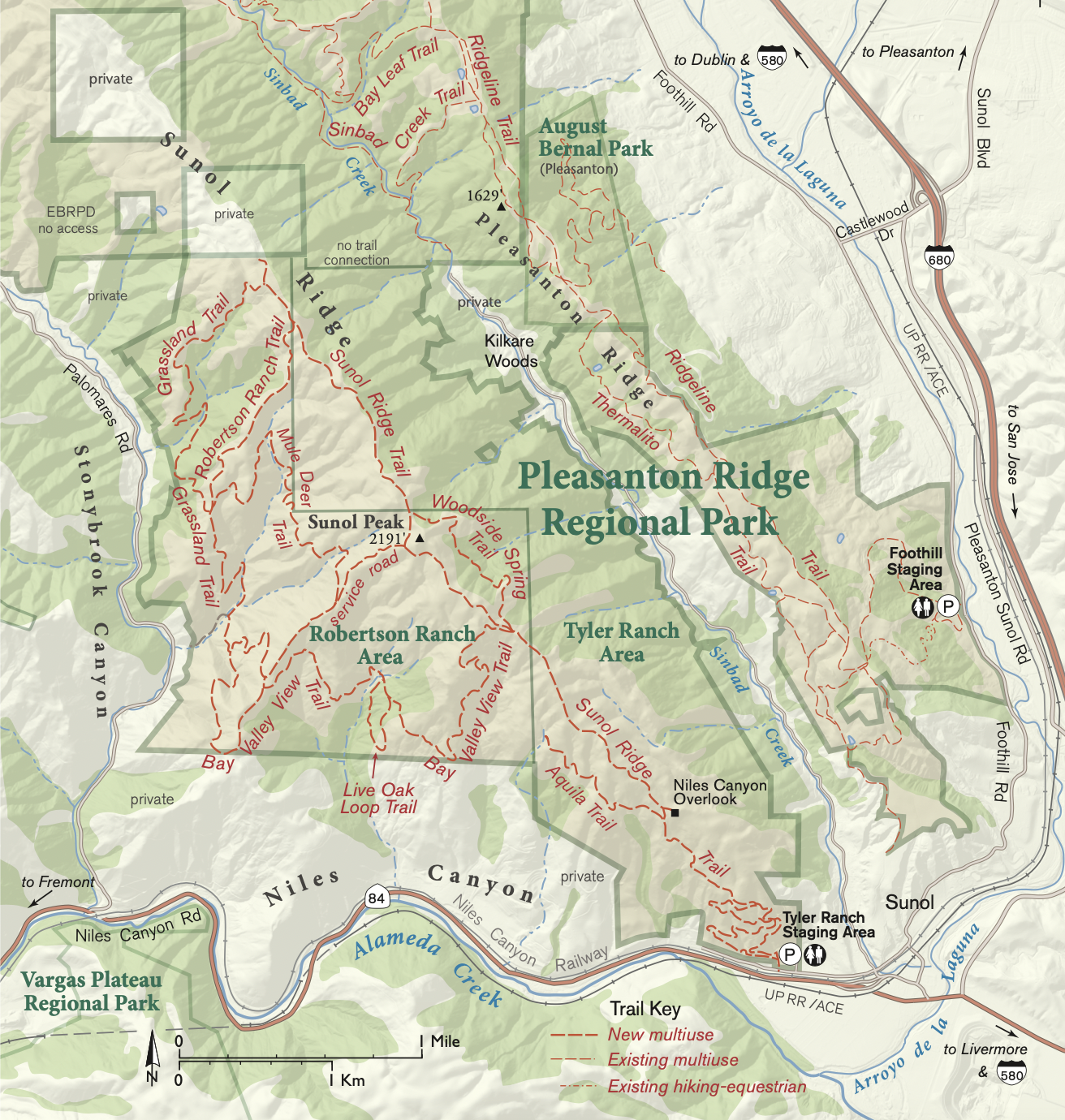

The Tyler Ranch Staging Area (12565 Foothill Rd., Sunol, CA 94586) is marked by a sign and the large white Foothill Farms barn. For more information and updates: ebparks.org/parks/pleasanton-ridge

• The new staging area consists of 70 parking spaces, four ADA spaces, and three equestrian staging spaces. Facilities include a vault bathroom, water fountain, information panel, bike rack, and small picnic area.

• Mountain bikes are allowed on fire roads and the Tyler Ranch Trail, with plans for more trails in the future.

• Horses are allowed on trails.

• Dogs are allowed off-leash except within 200 feet of any parking lot, trailhead, or staging area.

• The Sunol Ridge Trail is particularly good for wildflower viewing. The two-mile round-trip hike to the Niles Canyon Overlook gains about 800 feet in elevation.

Atmospheric river storms had been pounding California for nearly three weeks when finally the perfect sunny January day arrives to explore the rolling hills of Tyler and Robertson Ranches in the East Bay. Opened in late November 2022, these 2,800-plus acres have been added to the already 5,200-acre Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park. As I pull into the new Tyler Ranch Staging Area, near Sunol, I am greeted by my guides for the day: Ashley Houts, supervising naturalist, and Neoma Lavalle, a principal planner with the East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD), which manages the parks. We get acquainted while standing in front of the historic Foothill Farms barn, a reminder of the land’s cattle ranching days, while two red-shouldered hawks fly in circles overhead. It’s a sign that the land is coming alive again, jump-started into spring by the back-to-back storms.

Houts and Lavalle are excited to take me up the Sunol Ridge Trail, a steep yet rewarding walk that promises gorgeous views and an ascent through several habitats with a fantastic display of wildflowers in good rain years. The recent deluge suggests 2023 may well be one of those years and serves as a reminder of California’s unique Mediterranean climate: this is one of only five regions in the world with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters.

building of EBRPD parking lot for the new park. (Photo by Charlie Day)

The topography of the Bay Area further diversifies this extreme environment, with undulating mountains arranged roughly northwest to southeast that create rain shadows, shady canyons, rocky barrens, and sprawling plains where many of the East Bay’s towns have sprung up. The Coast Range’s orientation is caused by the San Andreas Fault, where the Pacific Plate slides northwestward along the North American Plate. The mountains and ridges themselves—the result of the ancient Farallon Plate subducting under the North American Plate—are the top layer of land scraping onto the North American Plate and crumpling like a piece of paper. Along the Sunol Ridge Trail, the soils are mainly well-draining sandstone in the hills, while the slopes and valleys are primarily shale, which holds water better and helps sustain the denser woodlands tucked away in the ridges.

The properties making up Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park (PRRP) are the ancestral homelands of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone, who continue to live in the greater Bay Area and who lived on and stewarded these lands for millennia before the arrival of European colonizers. With the beginning of the mission period in the 1700s, Ohlone were forcibly removed from their lands that were then parceled into ranchos and sold, predominantly to white Europeans. In 1869 the railway section through Niles Canyon, which runs from Sunol west to Fremont, was finished, overseen by railroad baron Charles Crocker and built primarily by Chinese migrant workers. The line connected San Jose to Sacramento along the first transcontinental railroad. The Tyler family purchased the land in the 1940s and ran a cattle ranching operation until 2009, when it was acquired by EBRPD, with a $1.73 million contribution by the Priem Family Foundation for a total of $6.63 million, for preservation and to again connect people with the land.

Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park. (Map by Ben Pease)

Tyler Ranch adds 1,476 acres and seven miles of trails to Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park, as well as an improved gated staging area for parking and facilities. Robertson Ranch, acquired in 2012, adds an additional 1,368 acres and 13 miles of trail to PRRP. Rising over 2,100 feet above the surrounding area, Sunol Peak is now accessible to hikers, who can see gorgeous 360-degree views of the East Bay or even view the Sierras to the east on a clear day. Vestiges of the land’s ranching history remain: the barn with the fading FOOTHILL FARMS sign; rusting barbed-wire fences marking old grazing pastures; and even a historic corral just a short hike from the staging area. While grazing cows may seem like a thing of the past here, these are working lands where EBRPD maintains a grazing program that keeps cows on the land and potential wildfire fuel loads low.

Oak Woodland Flowers

As we begin our ascent on the Sunol Ridge Trail, we pass massive oak trees that are just starting to produce the new year’s growth. Species along the trail include blue oak, California black oaks, and coast live oaks. Dispersed among them are the strange yet beautiful California buckeye, which shed their leaves in the winter, laying bare smooth gray bark and pendulous fruits, only to give way to green leaves and towers of white flowers come spring. These species are the primary components of an oak woodland, one of the main ecosystem types on Sunol Ridge and a common sight in the Bay Area.

Underneath, growing in dappled sunlight, are plants like the early blooming Indian lettuce, a small annual wildflower with white blooms emerging from the center of saucer-like leaves. Indian lettuce deploys a dispersal strategy known as “explosive dehiscence” where its seeds erupt violently from the mature fruit at the slightest provocation. This ensures that seeds spread several feet from the mother plant and create a robust seed bank in the soil. Also look for the parasitic herb valley tassel, which can form small white-and-red carpets with flowers that resemble owls! They take nutrients from other plants by penetrating their host’s roots with specialized organs called haustoria and siphoning off what they need. Johnny-jump-ups are a cheery yellow violet that hosts a variety of butterflies. Shrubs such as the hillside gooseberry are well armored with spines to deter herbivores, but sport beautiful fuchsia-like flowers that develop into equally painfully defended fruits.

Riparian Wildflowers

As we continue onward up the steep trail, the sounds of civilization give way to gentle breezes and the bubbling of long-dormant springs that have popped up in the last few weeks. Below us the usually gentle Alameda Creek is roaring through Niles Canyon, shimmering and swollen with the recent rains. As we stop at a lookout ringed with towering oaks that was just a short distance up the trail, the snow-topped peak of Mount Hamilton rises into view. The moisture gradient in these hills becomes more obvious from a higher vantage point: shadier north- and east-facing areas support stands of trees that are protected from the desiccating sun, while the comparatively exposed southern and western areas dry more quickly and are green with grass or coastal scrub.

These cooler, wetter habitats in the park, found along the Bay Valley View Trail and elsewhere, are home to riparian species like the aromatic California bay tree. This tree, the only member of its family native to California, is a holdout from a colder and wetter time millions of years ago when it was joined by its cousins in the genus Persea, famous for having the avocado tree in its ranks. California bay fruits even resemble small avocados. Additionally, white alders exist in the wettest areas, sporting last year’s fruits, which look remarkably like redwood cones but don’t be deceived! They aren’t conifers at all, but members of the beech family.

Under the canopy in wetter areas, a whole different suite of wildflowers can exist. Milkmaids, a pretty little white-flowered member of the mustard family, is one of the first spring wildflowers to pop up. Look for its four-petaled flowers and deeply lobed leaves from January to April. The ethereal hillside woodland star often blooms from March to May, with long thin stems crowned in fringed white flowers. Several of the most captivating species in the area include checker lilies, a brown-and-yellow checkerboard-patterned flower blooming from late February to April. These plants sometimes take a year off from flowering and produce instead a single “feeder leaf” from their bulbs, a large and flat leaf that soaks up sunlight and builds energy stores for use when the plant flowers. Giant wakerobins are one of the largest members of the genus Trillium and are notable for their variable flower color, ranging from white to green to dark red. Blooming from February to April, the leaves also have a mottled pattern unique to each individual. These plants are geophytes, species that have adapted to summer droughts by modifying their roots into fleshy energy-storing organs. They persist after aboveground plant parts die back, waiting, dormant, for the winter rains to begin the process again. Be careful not to disturb these plants, as it can take several years for them to reach maturity!

Meandering along the upper portion of Sunol Ridge Trail, we come upon the resident cows basking in the sun in an open grassland. While centuries of grazing have converted open areas into ones covered mainly by invasive grasses and annuals, you can still find purple needlegrass, California’s state grass. This unassuming bunchgrass grows knee high, with roots that reach 20 feet deep. Having such deep roots is great insurance against drought, and individual plants are thought to be able to live for centuries. These areas along the Grassland Trail Loop have the best wildflower color in the wettest years, with the hills covered in splashes of California poppies and swaths of the aptly named goldfields, a minute annual member of the aster family that attracts pollinators with yellow flowers featuring a darker center circle and lighter-colored petal tips.

Coastal Scrub Flowers

The drier areas we encounter near the end of our trek toward Niles Canyon Overlook begin to transition into coastal scrub, an imperiled ecosystem unique to coastal California and northern Baja California. It is characterized primarily by low-growing, drought-deciduous, and often aromatic shrubs, nicknamed “soft chaparral” for the plants’ generally softer leaves and less woody stems compared to the leathery species typical of true chaparral. The ecosystem is exceedingly rare due to its occurrence in coastal areas highly desirable for development and grazing across California. It is also mostly relegated on our hike to steep rocky outcrops where the cows couldn’t eat it. Look for shrubs such as California sagebrush (be sure to get a sniff), bush lupines, sticky monkey-flower, and coyote brush. Coyote brush, while at first glance an unassuming shrub found throughout most of California, colonizes open areas and shades out grasses, while providing cover for small mammals to eat grass seeds and allowing more shrubs to take hold. Interspersed between the shrubs are later-season wildflowers like turkey mullein, pink clarkia, and the narrowleaf milkweed, a perennial wildflower that hosts monarch butterflies. If you look closely at its flowers, you may find small bugs that, while looking for nectar, have gotten a leg trapped in the tightly folded petals. The coastal scrub ecosystem is the jewel of the biodiverse region known as the California Floristic Province, and remaining areas should be cherished and protected.

Arriving at our destination for the day, the spectacular Niles Canyon Overlook, Houts and Lavalle spot a resident golden eagle diving into the nearby oak woodland. These are some of the largest birds in North America, living and hunting in areas with canyons and open habitats. Seeing them in the golden hour of a winter day brings home the importance of conserved lands, like these, in providing critical habitat connectivity.

Descending back to the staging area, I can’t help but begin a mental plan for my next visit to see what wildflowers come up this year. Early-season rains almost always favor a great wildflower year, and it’s rare that places like these are so accessible to the public.