Chris Lyall and I are about to go where few hikers have gone before. We’ve just left the Westside Trail in the Brushy Peak Regional Preserve, following a faint track in the grass, probably made by a truck or off-road vehicle years before. We climb steadily and steeply uphill; the track narrows to a slender path that forces us to go single file. At times it fades away altogether, prompting Lyall, a ranger with the East Bay Regional Park District, to pause and get his bearings. He’s one of the small number of people who have been here before, but that was just once, a year ago, and the survey stakes he planted then have vanished in the rains that inundated the region a few weeks ago.

Not that we’re in any actual danger of getting lost. Lyall knows Brushy Peak quite well, and we’re only a half mile or so from several well-developed, well-marked, and well-visited trails that crisscross the property. Lyall is taking me along a route that the district is planning to turn into a hiking trail in the not-too-distant future.

I’m also learning that creating a new trail isn’t as easy as it might seem. It takes much more than erecting a few marker signs and getting some shovels to smooth out the rough patches in the dirt.

This new Brushy Peak Loop, as it’s being called, will add about a mile and a quarter to the Park District’s roughly 1,000 miles of trails in Alameda and Contra Costa Counties. About six miles of trails are already open in this 2,000-acre preserve, which was dedicated just last November.

The Bay Area is truly a trail-walker’s paradise. In addition to the trails on Park District lands, the East Bay has hundreds more miles of connecting and regional pathways, like the Bay, Ridge, and Skyline Trails—many of them maintained by the Park District—plus more in Mount Diablo State Park, on water district lands, and in city parks. Ranging farther afield, hikers can explore such spectacular locales as Point Reyes, Big Basin and Henry Coe State Parks, and the Mid-Peninsula Open Space District’s lands, just to mention a few. Even the most devoted and footsore trekker would need several lifetimes to explore all the trails in these parts.

The word “trail” conjures up images of a narrow pathway, perhaps running through a dense forest or pristine, wildflower-filled meadow. But there are actually several different kinds. The Park District has about 200 miles of narrow “single-track” trails—50 miles are for hikers only, while the rest also accommodate equestrian users. Paved trails cover 150 miles, while 650 miles are “multi-use”— dirt roads between 10 and 16 feet wide—and allow bicycles.

Lyall and I follow a narrow rut that parallels a seasonal creek. Cows grazing nearby look at us and move away, clearly annoyed at the intrusion. As we move higher, I see more and more large sandstone boulders scattered across the grasslands. We don’t climb Brushy Peak itself; instead, we aim for a saddle between the 1,702-foot peak and a smaller hill a quarter of a mile to the south. We gaze overhead, searching for the golden eagles that frequently prey on the numerous ground squirrels in the preserve. “I’ve never seen more golden eagles than in this park,” my guide muses. Indeed, this is raptor central. Already, we’ve seen northern harriers, kestrels, redtails, and a turkey vulture or two, and it’s not uncommon for visitors to spot ferruginous hawks here. Beautiful smaller birds are bountiful—we spot flocks of meadowlarks and flickers darting hither and yon, while the assorted chips and chirps of unseen songbirds emanate from the trees and bushes.

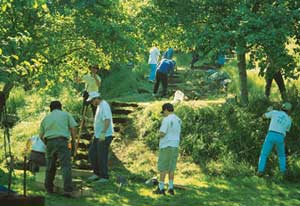

- Volunteer crews using hand tools do a significant amount oftrail maintenance for the district including rebuilding this sectionof stairs at Coyote Hills Regional Park near Fremont. Photo by TerryNoonan.

No golden eagles today, but I’m not complaining. When we reach the saddle (at about 1,400 feet, the highest point of the trail) we pause and look back toward Mount Diablo and an impressive vista of the East Bay hills. A few yards farther on, the view opens up to an equally magnificent overlook of the windmill-strewn Altamont Pass and the city of Livermore.

Why build a trail in this, or any, particular spot? “We want it to go to an interesting place,” says Jim Townsend, the district’s trails development program manager, “through a redwood grove, or perhaps to the top of a hill, along the shoreline, or to some other kind of natural or historic feature.”

Often, the district is able to use existing fire trails or ranch roads built by previous owners, or, in the case of shoreline properties, trails can be run along the tops of levees. This can save considerable time and effort, says the district’s trails coordinator, Terry Noonan. He notes that the trails already open at Brushy Peak are all former ranch roads. One segment had to be moved away from a creek, but otherwise the job was pretty simple. Crews had to do some regrading, and install articulated concrete blocks to create a “ford” across several perpetually wet parts of the trail, but on the whole the original roads were reasonably well-built.

When it comes to carving out new trails, however, things can get considerably more complicated. The ranch roads mainly traversed grassland, now largely overgrown by non-native plants such as ryegrass and wild oats. But the rest of the preserve is a complex ecosystem, with seasonal pools and streams, live oak and buckeye woods, and shrubland dominated by California sagebrush. Although the preserve does not support any endangered or threatened plant species, there are populations of rarities such as stinkbells (Fritillaria agrestis), yerba mansa (Anemopsis californica), and Nuttall’s alkali grass (Puccinellia nuttalliana). Special status animals known to live at the preserve include San Joaquin kit fox, California red-legged frog, California tiger salamander, loggerhead shrike, prairie falcon, white-tailed kite, burrowing owl, and the aforementioned golden eagle. These are factors that can make planning and building new trails more difficult.

In addition, Brushy Peak was once an important site for local Native Americans. Members of the Ssaoam subgroup of the Ohlone people lived in the nearby hills, trading with other Indians from the Central Valley and the coast, moving on trading routes that crisscrossed the region. In fact, says district naturalist Cat Taylor, some of those routes remain today—underlying major freeways. “Interstates 580 and 680,” she says, “mark former trade routes [for] rabbit fur blankets from the San Joaquin Valley [Northern Valley Yokuts] to the San Francisco Bay [Ohlones] along 580 and between Ohlone and Bay Miwoks along the I-680 corridor.”

Native Americans regarded Brushy Peak itself as sacred, using it for cultural and ceremonial events. In order to protect remaining Native American artifacts, the hilltop itself will probably be accessible only on guided tours, much the same way Vasco Regional Preserve is.

Trail building in sensitive habitats may require working with a number of state and federal resource agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), California Department of Fish and Game, the Army Corps of Engineers, the National Marine Fisheries Service, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, and in the case of shoreline projects, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. Authorization from some or all of these agencies may be necessary before the first spade goes in the ground.

The Park District tries to head off conflicts with the state or feds before they get started, says Stewardship Manager Joe DiDonato. His department gives trail proposals a thorough environmental review, trying to anticipate—and solve—problems that outside agencies might find. “It saves us a lot of headaches,” he says. DiDonato and his staff map out such things as rare plant and animal populations, and if necessary, move the trail away from their habitats.

The process doesn’t always go smoothly. The district and USFWS are currently trying to weigh habitat protection against public access along proposed shoreline trails in Hayward and Richmond. The public will likely want to get a close look at the marshes, but the trails might need to be routed farther from wetlands in order to minimize disturbance of nesting and foraging shorebirds.

The key is finding the right balance between access and protection, says Elizabeth Murdock, executive director of the Golden Gate Audubon Society. “Human activities can have a big impact on birds and other wildlife. I also really believe that getting people out to see, enjoy, and explore is the first step in protecting wildlife areas.” Well-planned access can help shore up public support for funding of open space purchases and restoration projects. Says Townsend, “If you expect people to support [these projects], you need to let them see what they are paying for.”

Trails can have both positive and negative impacts on the natural environment—both in themselves and when people use them. They may create an artificial “edge” effect—the juncture between two separate ecosystems.

The effects on plants differ considerably, depending on the landscape and existing conditions of the site. Disturbing the soil can create favorable conditions for invasive species, especially if there are already stands of these plants growing nearby. A variety of thistles—yellow star, artichoke, purple star, and Italian among them—are unwelcome nonnatives that spring up along trails. These are sometimes joined by wild fennel or puncture vines, the latter named for the sharp spines that can cause bicyclists grief.

Some natives, especially pioneer species, can thrive along trails. California oat grass sometimes takes hold where the soil has been cut and filled during construction. Serpentine linanthus, a species that favors nutrient-poor, rocky soil, can sometimes be found on trails in the Ohlone Wilderness. “It will be growing right in the middle of a jeep trail,” says district botanist Wilde Legard.

The impact on animals can also be variable. Allowing people too close to a golden eagle’s nest or fox den may cause the animals to abandon their young. All too often, people leave garbage, attracting feral cats, crows, and gulls, which in turn invade nests or decimate local rodent and amphibian populations. Vegetation, especially in riparian areas, is sometimes trampled by careless walkers or bicyclists, and the seeds of invasive plants can be tracked in by hikers, bicyclists, and equestrians. Migratory shorebirds that have been flushed out by dogs lose valuable feeding time and energy they need to complete their journeys.

On the other hand, some critters seem to use the pathways that people have created. Naturalists frequently see signs of deer, raccoons, mice, and snakes on or along trails, and mountain lions apparently use them as well. Raptors hunt in the cleared swath of land, and smaller birds that feed on open ground are often seen pecking at the ground in the middle of a trail.

There is little hard data on the subject either way, says DiDonato. “We can’t confidently say that this trail will have this effect on this species.”

- Lee Rutter (left) and BK Doyra (right), off-duty volunteersfor the Park District’s Mounted Patrol, ride in Redwood RegionalPreserve. The Volunteer Trail Safety Patrol, which also includeshikers, dog walkers, and bicyclists, works primarily to encourage safeuse of trails once they’re built. Photo by Scott Hargis.

Nevertheless, trail designers use a number of mitigation measures to minimize potential damage to the environment. Boardwalks constructed over wetlands reduce soil compaction and confine foot traffic to a narrow area. Tall plants along trail edges can shield nearby animals from human intrusion. Trails can be regraded, or even paved, to reduce erosion, and fences can be installed to keep dogs away from critical habitat. In addition, ongoing maintenance measures such as controlling invasive plant and animal species and repairing seasonal erosion may be needed.

But everyone agrees that the best mitigation is to properly situate and build the trail in the first place. Trails can be a form of crowd control—steer people in the right direction, and there’s less chance they’ll end up trampling rare plants in the middle of a meadow or tripping over plover nests along a shoreline. On occasion, trail designers must compromise—if there’s a particularly spectacular view, or beautiful lake, for example, people are going to find their way to it. A well-planned path can encourage people to take a less destructive route.

“When you design a trail, you can decide what you want to show, and what you want to hide,” says Seth Adams, executive director of Save Mount Diablo. He points to the new Tassajara Creek Trail on Mount Diablo. The path could easily have been built through an impressive stand of native grapevines. “People would have been swinging from them—pretty soon the vines would have been gone,” he says. Instead, the trail was routed to avoid the fragile plants.

“It’s tough. People want to be everywhere,” says Sheila Larsen, a senior staff biologist with USFWS. The agency does have regulations governing trail design, but they are somewhat flexible. Larsen says that trails are not supposed to be built within 300 feet of riparian areas, but USFWS may require the trail to be set even farther back if there is steep terrain or loose soil that could cause siltation problems. Or it may allow the trail to be built closer to the water in order to avoid sensitive upland habitat. “(The rules) aren’t set in stone,” she says. “I think that trail siting is more art than science.”

Even on our short walk in the Brushy Peak Preserve, Lyall and I have traversed a variety of terrains and ecosystems, each requiring different approaches to trail layout and maintenance. As we descend from the saddle, we pass by the squat, windblown live oaks that cover much of the hillside, and into the shadow of high, jagged sandstone outcroppings.

Lower down, we encounter thick stands of sage, mixed with some very nasty-looking bright red stalks of poison oak. Avoiding the plants (at least as much for our sake as theirs), we work our way downhill back to our starting point.

My guide pauses to scan the sky one more time. “The eagles aren’t cooperating today. Usually I spot at least one.”

But he’s happy to keep trying. “I can’t wait until this trail comes in,” he says. “It’s going to be beautiful.”

The actual construction won’t be all that difficult—one boulder-covered section will need some extensive rock work in order to make it passable, but crews with hand tools will probably be able to do most of the job. The district has an active program for trail volunteers, and Noonan hopes that they will be able to help out.

In fact, says Jim Townsend, the Brushy Peak Loop will likely be one of relatively few trails built primarily with volunteer labor, probably some time in the next few years. But even more remarkable, says Townsend, is that this will be a new length of narrow trail—a more complex task than simply upgrading existing ranch and fire roads. “We just don’t build that many narrow trails anymore,” he says, “but here we’re working toward providing that ‘walking on a narrow trail’ experience. To get back to our roots.”

Lyall clearly hopes the trail will open soon. We get in his truck and drive up one of the other trails to check for possible erosion damage from the storms. A hiker walks up and asks when the loop trail is going to be open. The ranger explains the route planning and other work that has to be done before volunteers start building the trail. “It will be a while,” he advises the man.

“I hate having to say that,” Lyall tells me as we drive off.

.jpg)