On a cold, blustery day in late February, a group of killer whales known as “K Pod” was detected swimming down the coast of Northern California from an area around Fort Bragg. The route the pod embarked on that day was straight south, hugging the coastline. As they neared Point Reyes, a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) fisheries researcher in Washington State, Brad Hanson, who had been following the whales using satellite tag information, sent out an email alert to a group of marine scientists along the coast. This was a thrilling call to action for a marine scientist who has lived near Point Reyes her whole life, yet had seen killer whales only twice from land, and I didn’t want to miss this rare opportunity. I grabbed my binoculars and spotting scope and headed out to the lighthouse to see if I could catch sight of this wayward pod so far from its spring and summer home in the Pacific Northwest, and so near to shore.

Killer whales are toothed members of the order Cetacea (which includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises), but as members of the Delphinidae family, they’re more closely related to dolphins than to true whales. Globally, they’re lumped together into one species, Orcinus orca. Also called orcas, they’re one of the world’s fastest-moving marine mammals, able to swim at speeds approaching 35 miles per hour, easily outpacing slower whales such as the grays and minkes they sometimes feed upon. Their size (males can range up to 32 feet and weigh 22,000 pounds) strength, and ability to echolocate all contribute to their prowess as hunters.

But while killer whales are found in all of the world’s oceans, their lives in the wild are poorly understood, in part because there are tremendous differences between different groups of orcas. Though the species’ range spans the globe from pole to pole, individual orcas belong to regional ecological groups, called ecotypes, that have distinct ranges and behaviors. Scientists recognize at least 10 ecotypes for the species worldwide, three of which can be found off California: Southern Resident, Transient, and Offshore. While our classification of orcas is likely to change as we learn more, our growing understanding of these orca ecotypes — bolstered by recent advances in research technology and protocols — has been a major key to unlocking the mystery of the killer whales of the eastern North Pacific.

The Southern Resident ecotype was one of the first groups of Pacific orcas to be classified. In the 1970s, scientists learned how to identify individual whales by taking photographs and then studying the images to identify distinguishing characteristics such as size and shape of fins, nicks, scars, and markings on the saddle patch, the distinctive mark on an orca’s back just behind the dorsal fin. The photos were collated into catalogs and used to compare whales and pods (groups of whales that are closely associated by behavior and genetics). In 1976, Ken Balcomb of the Center for Whale Research used this technique to identify all the individuals in the three pods (J, K, and L) of killer whales that live around the San Juan Islands of Washington. Thanks to this research, we know that the Southern Resident ecotype is composed of three pods consisting of 20 to 40 individuals each and genetically tied through their mothers. The population size of this ecotype (as of summer 2013) is 82, small enough to census all the individuals within it each year.

But even as the photos helped identify the individuals of the Southern Resident ecotype and document the relationships be-tween them, another mystery soon emerged: Where did these Southern Resident whales go in the winter? Photo identification only works when the whales are present, breaching the surface in front of a human with a camera. For years, anecdotal sightings off the coasts of Oregon and Northern California, including some from as far south as Monterey Bay by marine biologist Nancy Black of Monterey Bay Whale Watch and others, suggested the whales moved south along the coast, but documentation was lacking.

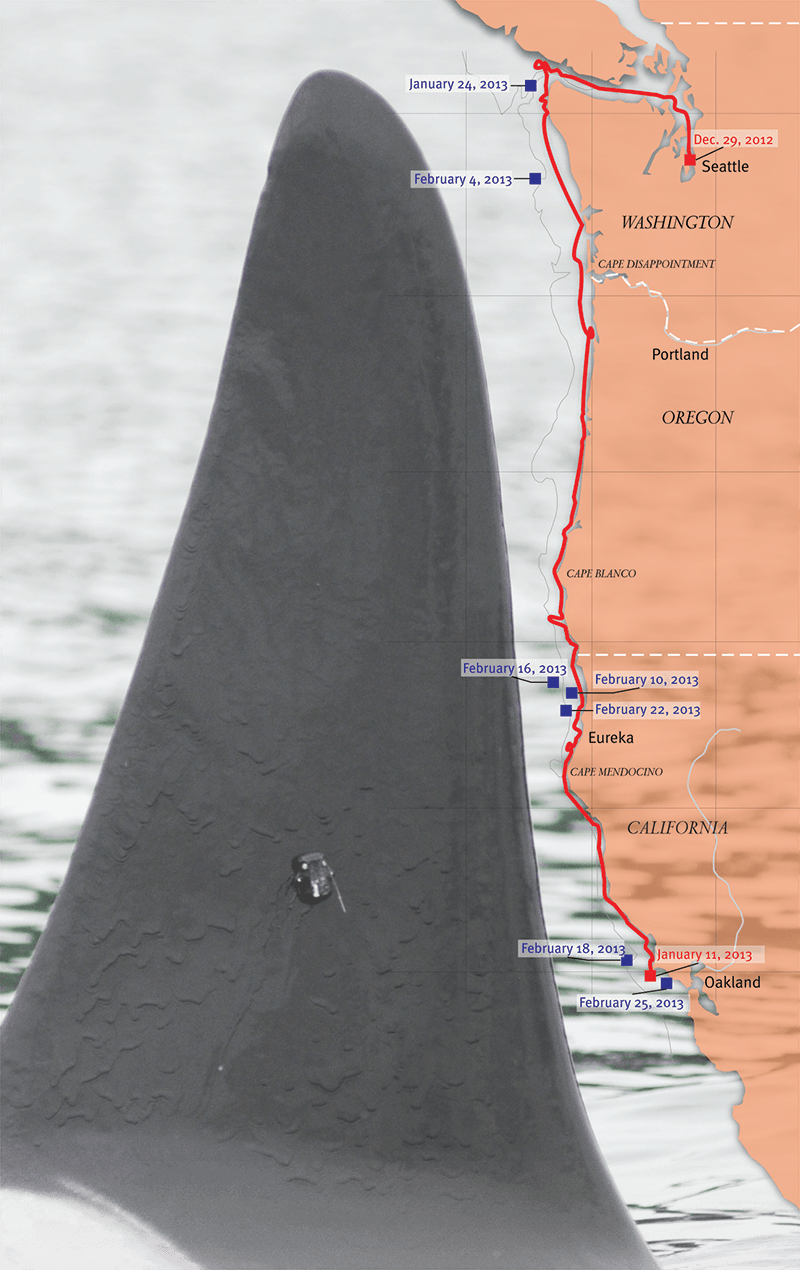

We’ve recently started to fill this knowledge gap with the help of satellite tagging. To tag an orca on the open water, though, is no easy task; it requires a special understanding of the whales’ behavior and ecology, as well as extraordinary finesse. Greg Schorr from Cascadia Research Collective has both, and in 2012 he and NOAA’s Hanson were able to attach a tag to the whale that was heading toward Point Reyes. Hanson told me how Schorr tagged the tall dorsal fin of this Southern Resident K Pod male with a dart gun at a distance of around 25 feet in the waters off the Washington coast. The tag was an ARGOS (Advanced Research and Global Observation Satellite) system device, programmed to record the location of the orca for short periods throughout the day and transmit that information to satellites, which were then accessed online by biologists.

The effort to tag and follow the Southern Resident whales matters because, while the population was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2005, marine resource managers had little information on which to base protective measures outside of the whales’ Washington/British Columbia home range. With the tag affixed, scientists were able to follow K Pod south to Fort Bragg, where the whales appeared to be feeding near the shore. The tag continued transmitting for 94 days, mapping the transit of the whale in near real time and allowing Hanson’s group to follow along the coast by car and intersect the pod by boat, collecting even more precious information about the pod’s winter habits and location. Email alerts, like the one I received, enlisted more trained observers in the study. Through photographs of other individuals in the pod, Hanson and his group were able to identify the male’s traveling companions. And from collected whale poop samples they were even able to determine what the whales had been eating on their journey. This new information will greatly expand our understanding of Southern Residents and help guide recovery efforts.

While Southern Residents stick mostly to their home in the Pacific Northwest and are rarely spotted in California, whales from the Transient ecotype are much more commonly seen in our waters. Transients can be identified visually by their robust size, solid saddle patch, and tall straight dorsal fin of the male, compared to the open saddle patch and slightly curved tip of a Southern Resident male’s dorsal fin. The females’ dorsal fins in all ecotypes are much shorter than the males’ and they’re more curved, similar to those of dolphins. Transients are frequently observed in and around Monterey Bay, though they have been observed as far north as southeastern Alaska and as far south as Southern California. According to noaa, there are around 100 individual Transient orcas off the California coast. As researchers have begun to better understand the Transients, they have divided the ecotype into West Coast Transients that range from Southern California to southeast Alaska and a second group that occurs farther west through Prince William Sound, Kodiak, and the Aleutians. Transients of either group generally occur in small pods of 10 whales or fewer.

Scientists use differences in morphology, diet, range, behavior, and genetics to distinguish between ecotypes. They also increasingly use acoustic differences. With an underwater hydrophone, researchers can hear the echolocation clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls of the whales as they communicate, then compare the calls with those of other groups. This method of detection can also be quite useful for finding whales, especially when rough seas make sightings difficult.

Combining acoustic signatures with behavior has yielded some remarkable insights into the attack patterns of Transient whales in Monterey Bay. In contrast to the fish diet of Southern Residents, Transient orcas feed primarily on marine mammals. Over the past decade, Nancy Black and other researchers have documented Transient orcas attacking and eating gray whales in Monterey Bay. It’s a perfect setup for the orcas: In April and May, mother and calf pairs of gray whales migrate slowly north from their breeding lagoons in Baja and warm waters around the southern Channel Islands, generally hugging the coastline. But rather than follow the long perimeter of Monterey Bay, they strike out more or less directly across the bay, using knocking sounds to navigate back up the slope on the north shore after crossing over the deep canyon. This gives Transient orcas the opportunity to detect the gray whale pairs in the open water. In 2004, Black documented 16 attacks by Transient orcas on gray whale calves. She noted that the several core family groups of orcas, numbering seven or less, gathered into groups of 15 to 32 individuals, all working together and sharing the kill. The adult reproducing females did most of the work while the young closely observed, though some males also participated.

Researchers also discovered, by listening with hydrophones, that the Transient whales go silent before attacking; successful attacks are followed by a burst of vocal calls and whistles. Southern Resident whales do not go silent before preying on fish, presumably because fish don’t detect their vocalizations. Harbor seals, though, know the difference between these two ecotypes and are known to ignore vocalizations of fish-eating Residents but react strongly to those of their Transient cousins.

Much less is known about the vocalizations — or any other aspect — of the third ecotype, Offshore orcas, because they are so rarely encountered. However, when they have been detected, scientists have noted that their vocalizations are distinct from those of the other two ecotypes.

One final way of learning about orcas is to study the rare cases in which whales have died and washed ashore. Perhaps it was fitting, then, that researchers here were able to learn about the rarest of the ecotypes through this rarest of study methods.

In November 2011, while most of the region’s orca specialists were away at a marine mammal conference, a local beach walker discovered a dead whale that had washed ashore on a remote beach at Point Reyes. Generally, when a dead orca washes ashore, scientists try to gather data before the carcass decomposes, and fortunately there was one local marine mammal biologist not at the conference. Moe Flannery of the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) gathered a corps of volunteers to collect information and tissue (blubber, skin, and muscle) from the whale while it was fresh. Flannery also shared photos of the dead orca via email with other researchers, hoping for possible identification. The response was prompt and unexpected: Graeme Ellis at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada wrote back identifying the whale as a young male called o319.

The “O” stands for offshore, by far the rarest and least-understood of the three Pacific orca ecotypes and something extremely remarkable to find washed up on the beach in Point Reyes — or anywhere. Offshore whales are generally a smaller form than those of the other two ecotypes and their saddle patch is fainter. As with the other ecotypes, the female’s dorsal fin is much shorter than the male’s, is rounded at the tip, and often has nicks, and the male’s fin is shorter than those of the other two ecotypes and additionally has a rounded tip. Researchers first identified the ecotype off the Pacific Northwest, but Offshore individuals and pods have subsequently been observed ranging far across the eastern North Pacific from the Bering Sea south to California. Once, they were observed and photographed by a volunteer at Point Reyes, exuberantly leaping after rounding the point. Orca researchers were able to identify the pod from the photograph of a male, adding the observation to their database. Researchers believe that Offshore orcas feed primarily on schooling fish and sharks such as Pacific sleeper sharks, blue sharks, and opah. Their teeth are often heavily worn, perhaps be-cause sharks have abrasive skin.

The orca known as O319 had originally been sighted in 2002 as a juvenile and had been photographed in the Pacific Northwest numerous times — including just two months earlier off the west coast of Vancouver Island. Based on its size and lack of secondary sexual characteristics like curled flukes and large dorsal fin, Graeme estimated that O319 was no more than 15 years old at the time of death, an age when males are starting to mature sexually. (Orcas can live as long as 90 years, though the average age of death for females is 50 years and for males 30, so this male died relatively young.)

The initial plan was to keep just the tissue samples and maybe the skull, but once Graeme had identified the dead orca as an Offshore, Flannery realized she needed to try and recover the entire skeleton, to archive it in the CAS research collection.

Tides, waves, and steep cliffs limited access to the beached whale, but this was a rare opportunity that couldn’t be passed up. It was a monumental task, requiring the assistance of many individuals and institutions. So the group of scientists and volunteers mobilized by the Marine Mammal Stranding Network made the trip to the beach to undertake the long, stinky process. The first step was to cut the whale into pieces to get it off the beach. Volunteers with ropes, stretchers, and strong backs then hefted the bones and body parts up a steep, narrow path to the top of a ridge and then along the path to the parking area. Sarah Codde, a national park biologist who was one of the first to see the dead whale and participated in the whole removal process, said that packing out the skull was the hardest task of all, requiring six people using a stretcher and ropes. The necropsy, begun in the field and completed later in the lab, revealed hemorrhaging in the head, a broken rib, blood-stained vertebrae, and blood in the pleural cavity, indicating that the orca had died from trauma, perhaps caused by another orca or a boat strike.

Once the full skeleton had been brought to CAS, scientists and volunteers used a process called maceration, in which bones are soaked in water for long periods, to remove the remaining flesh and grease. Soaking off the flesh took two months, and degreasing to whiten the bones with sodium perborate took another four months. Finally, in March 2013, the skull was moved to the CAS roof so the sun could complete the whitening and degreasing.

Lee Post was chosen to orchestrate the next stage, the articulation of the bones. Post, known as “the Boneman,” is a resident of Homer, Alaska, who wrote the series The Bone Building Books and had worked on a similar project at the Marine Science Center in Port Townsend, Washington. The CAS project was unique, however, because the entire articulation process was done in full view of the public inside the museum. Under the gaze of fascinated visitors, CAS staff and volunteers carefully assembled all 286 pieces of the skeleton—a jigsaw puzzle of whale-size proportions—over the course of two months. John Eleby, a volunteer articulator and national park ranger at Point Reyes, participated in the entire process of handling the cleaned bones, including sorting, identifying, measuring, weighing, and mapping, and finally attaching the skull and lower jaw to the remainder of the skeleton.

Once completed, O319’s skeleton was put on display as part of the “Built for Speed” exhibit at CAS during the summer of 2013. It is now on permanent exhibit in the lobby at CAS.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Articulating O319

For more about the reconstruction of O319, read our story about Lee Post, head over to the California Academy of Science’s orca articulation blog, or watch the Academy’s time-lapse video story below:

While we have learned a lot from this rare beach-cast Offshore orca and from the satellite-tagged Southern Resident, there is still much to be discovered about these remarkable whales so we can properly manage our marine resources and give orcas a chance to survive in a rapidly changing marine environment subject to rising water temperature, acidification, and declining food resources. If, for example, scientists discover that Southern Residents feed only on Chinook salmon all the way south to Monterey Bay, should fisheries biologists revise how these salmon are managed along the Pacific coast? Whether orcas can adapt to such changes will be the subject of future scientists’ research, applying constantly evolving technologies not even imagined today.

Many orca researchers believe that there may be two new ecotypes in the eastern Pacific. An “L.A. Pod” was identified in the 1980 and ’90s near Los Angeles with individuals that are much smaller and display more superficial gashes compared to the other three ecotypes. (Members of this pod were filmed in 1997 just off the Farallon Islands attacking and killing a great white shark, a behavior not observed before or since in orcas.) And a research group led by Jaime Jahncke, a marine biologist with Point Blue Conservation Science, observed another previously unidentified pod of five killer whales during a research cruise in July 2013, directly west of the continental shelf near the Farallon Islands. The whales looked similar to Transients but members of the pod did not fit any of the photo-IDs for California. With the continued discovery and potential identification of new ecotypes, efforts to protect and restore these populations become both more illuminating and more challenging.

Back at Point Reyes, I waited out near the lighthouse for several hours on that raw February day, straining to see the bold black-and-white markings against the gray seas, but I never saw the tagged male of K Pod. I found out later that not long after I had arrived at the lighthouse, the pod had turned around near Tomales Point, just beyond the range of my spotting scope, and headed back toward Fort Bragg. Why? We’ll never know. But we know they did eventually come back. According to the satellite data, the K Pod did visit Point Reyes another time that winter — at night when no one was looking.