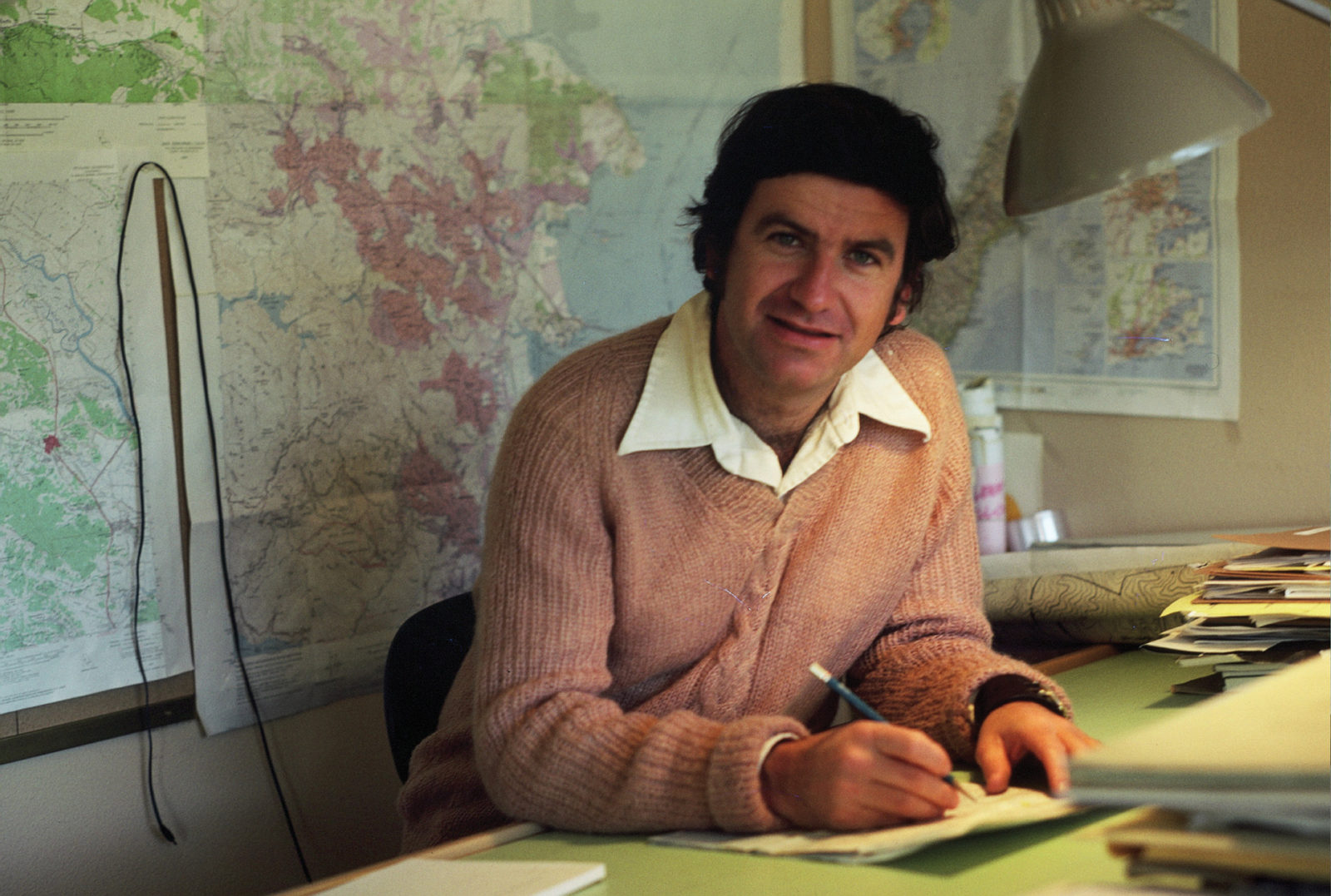

Twelve-year-old Dave Hansen sailed through the Golden Gate for the first time in 1956, as a young immigrant from New Zealand. The Bay Area stuck with him: After living in Kansas and Seattle and serving a three-year Peace Corps stint in Brazil, he returned in the late 1960s to pursue a landscape architecture degree at UC Berkeley. He wrote his thesis on the redesign of the Oakland Zoo and planned to become a zoo designer … but then one day his landlady saw an advertisement for this new kind of job, as an “open space and park planner” in Marin. Hansen applied, got the job, became Marin’s first full-time open space planner, and never looked back. Hansen’s influence on Bay Area open space now is hard to overstate: He’s variously worked as a planner, land-acquisition manager, and trail designer for the Marin County Open Space District, land manager at the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, and the first general manager of the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District. He also has served or serves on the boards of the Bay Area Open Space Council, Bay Area Ridge Trail Council, Friends of the Petaluma River, Marin Open Space Trust, and LandPaths. Among his North Bay accomplishments are public open space parks and preserves like Olompali, China Camp, Mount Burdell, Lucas Valley, and Roy’s Redwoods—where hikers can now walk the David Hansen Trail.

ES: What was it like coming over to be an open space planner in Marin in the 1970s?

DH: My boss Pierre Joske was my inspiration. He said, “David, I want you to spend at least 50 percent of your time outdoors looking at the landscape.” So I did! I’d run out there and look at every piece of property: ridge and upland greenbelts, streams and creeks, bayfront lowlands. The county was still very middle-class. But there was a strong ethic [aiming] to protect the hills around the communities, and to create community separators. People really wanted to protect what they could see outside their back door.

ES: You’ve got the entire geography of the Bay Area on your resume. Were there common challenges for conservation across these regions?

DH: Each place was unique. There was a uniqueness to how the open space districts were formed, starting with the East Bay back in the 1930s. Down on the Peninsula, there was the feeling that we’ve lost just about everything in the Valley of the Heart’s Delight; it’s all paved over. What have we got left to protect? It was the hills and the bayfront. In Marin it was protecting what’s around and between the cities, and the quality of life. Always focused on the community’s quality of life in each special natural setting. In Sonoma County, it was vast. That’s why it’s an agricultural preservation and open space district.

ES: The Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District has just passed a bond measure that includes shifting focus from acquisition to stewardship. How has that balance fluctuated over your years in open space work?

DH: I think in the early days of all these districts, the focus was always primarily on acquisition. There was huge demand down at Midpen for the public to get out on their property. As there was in Sonoma County. Despite the marching orders I had up in Sonoma to preserve open space mainly through conservation easements but not add trails or fee lands for public access, there was tremendous pressure to allow the public on lands they had paid to protect. There’s never enough open space anywhere. When you get overuse, like on Mount Burdell, the only thing we can say is, “You gotta buy more land! There’s gotta be more accessible land!” It’s the key. But at a point you run out of it.

ES: What kind of stories do you remember from the early days?

DH: The classic is Cascade Canyon in 1974-5. That was the first purchase I was really involved in. One of the women on our commission at the time, named Karin Urquhart, as a kid she’d been raised in Fairfax, and had always gone up onto this property, the Elliott Property. [Floyd Elliott, then-mayor of Fairfax] stopped her one day and said, “This is private property; you shouldn’t be here.” And she, a young girl, said, “Well, you don’t own this property. This land should belong to everybody.” And in fact it ended up that way. It was a great purchase, because the funding was assisted by an area family whose daughter had just been killed, so the family called me to see if they could help out the district in some way and dedicate something to their daughter. So they gave money for the purchase, and I got USGS to name the ridge Pam’s Blue Ridge. And I designed a plaque that’s still up on Blue Ridge.

ES: What other trails or acquisitions do you remember putting together?

DH: One success was working with George Lucas on the lands he was buying out west of Lucas Valley. I worked hard with them on a pedestrian and biking tunnel under Lucas Valley Road that connects the Big Rock Trail to the Loma Alta Fire Road, and on the 11 miles of trail he had to dedicate [as mitigation] and 800 acres of open space as well. We got a lot of trail and open space out of that development.

I was very involved with Roy’s Redwoods near San Geronimo. That’s why they were nice enough to name a trail there after me. Roy’s Redwoods was owned by a family that had a bunch of cattle and horses in there tearing up the landscape. We were trying to get the area around the big trees, some of which we think are 2,000 years old. Some of them were taller—I actually had the county surveyor go out and measure—than the Muir Woods trees. So I remember calling Jean Berensmeier—she’s kind of the duchess of the San Geronimo Valley, she’s fought for open space in the valley—and saying,

“Jean, I’m sorry to say, we weren’t able to do what we planned in terms of protecting the redwoods. We wanted to get the crucial 30 acres. But we’ve actually got an additional 300 acres to add to it.” She was just ecstatic.

We also worked a lot down in Tiburon. At the time Ring Mountain was owned by the Nature Conservancy. We’d pushed them to own it for the same reason we pushed the state to pick up China Camp and Olompali, because we knew we couldn’t manage all of those properties. Ring Mountain had these endangered species, so the Nature Conservancy was the ideal entity. But they eventually turned it back over to Marin County Open Space, after we got a bigger land management staff. Olompali has become a state historic area, but field staff and I had to manage that property for two years after we jointly acquired it with State Parks.

ES: Describe the China Camp acquisition and cleanup.

DH: China Camp was a mess. It had been the first site of the Renaissance Faire. It was full of 10,000 tires, and there was a ghastly murder: A Terra Linda girl had killed her parents and burned them out there. A lot of bad things, like drugs, happening out there. But off-road vehicles was the biggest issue. In those days, controlling off-road vehicles was a tough, tough thing for the county. I designed a whole system that’s still in use today—all these entry gates and fences you see around the Marin open spaces, that was my original design. The plaques, the signs, the stepovers. So we pushed the state [on China Camp] and they eventually picked it up.

At Olompali, we had to kick out some stable operators who were running horses over everything. We had Dutch elm disease we had to deal with. The adobe was wide-open and deteriorating rapidly. So we fenced off the garden, fixed the Dutch elm.

I talked to Mickey Hart, the Grateful Dead drummer, about when he lived there with other members of the Dead, and he used to ride his horse around everywhere with his dogs and ride the freeway frontage all the way to San Rafael. But he said, “We never got stoned out there. The only time I got high was when we were playing cards up in one of the valleys. The king started coming off the card.” I said, “Oh yeah, Mickey, OK.”Anyway, I’ve got a million stories about each property down here. And up in Sonoma County, too.

ES: Do you ever see people out in the parks or open spaces and think, I helped make it happen!?

DH: Like every old guy, you like to reminisce about the days when. I think back on these stories when the place was overrun with off-road vehicles. You don’t imagine that in Marin. But in those days it was.

It’s a nice feeling, because I get to use all these parks now. I have a backpacking group and we do a monthly local day hike as well. We did Rush Creek last month, and were at Olompali last week. These are my buddies; some of them I’ve hiked with for 40 years; we love going back to these places. It’s such a rewarding feeling. I envision my grandchildren hiking these properties in the decades to come.

But you can’t really dwell on it. There’s so much still to be done; that’s the big thing. I know people look at places like the summit of Bald Hill, and other hills around East Marin, and say, “That’s all open space.” Well it’s not! Up in Sonoma, there was always an informal relationship between Novato and Petaluma about keeping that corridor between them open, either as agriculture or open space. There’s no formal arrangement and the pressure’s on that all the time now, particularly with the highway widening that’s going on.

It’s a constant. At the Bay Area Open Space Council we say, “We’ve protected a million acres.” Well, we’ve got a million to go!

ES: What do you remember about the early days of the Ridge Trail Council?

DH: I worked on the first dedication down at Midpeninsula. We had a double dedication that day, at Purisima Creek and one of the San Mateo County parks, working with Brian O’Neill, superintendent at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, who was also chair of the Ridge Trail group. We did a huge flurry of dedications early on, mostly on public lands that were already protected. But now the tougher part has come, where you’re negotiating for whatever you can get, on private lands. Or looking for new alignments, like up to Mount Saint Helena. It’s a bit like when you’re riding a bike and you shift into a higher gear where it’s harder to push, you can feel the push, you’re trying to get every little piece you can.

ES: What’s the best trail you’ve ever designed?

DH: I’ve actually built a lot of trail — the first trail I ever did was out here in Marin, on San Pedro Ridge. Which was steep. Just four of us building it in a day, that was all we did. I was going ahead—I was the alignment planner—whacking stakes in the ground. We had two high school kids behind us, clearing the duff; Ron Paolini, the ranger, was in the back, cutting tread. Very rough tread. I hit a wasp nest, wasps went over my head and hit these kids, and of course everybody’s sweaty. That trail is still there! But they’ve adjusted it now so it’s got a little better grade.

The nicest one, I think, is the one up the hill out of Lucas Valley from Big Rock. That trail is spectacular. I did the preliminary design and [Ridge Trail steward] John Aranson changed my alignment a little bit, because he’s the real trail builder. I love that trail. People think it’s going to be tough to go up to 2,000 feet at the top of Big Rock Ridge. But if you take that trail it’s easy! Just a steady climb at 7 to 9 percent, which is an ideal grade.

So Big Rock is my favorite. But I should say the David Hansen Trail!