Mona Caron leans over the edge of a creaky blue scissor lift 20 feet in the air and points to a spot on the sun-drenched wall in front of her. “This is the tip of the leaf,” she says. Then she checks her harness—a thin loop of straps clipped to the railing. She’s eye level with the tops of the sidewalk trees and ear level to the insistent bursts of jackhammers that ricochet from the scaffolded building-in-progress across the street.

Today, Caron is adding something green to the landscape. She squints at the outline of a giant leaf spreading across the wall in front of her. The scissor lift platform sways with her slightest movement—she says it’s like standing on a piece of pudding. But she’s used to it. She steadies herself and crouches down to open a box of paints—revealing a rich array of verdant hues. She spritzes water on them, and dips her brush in.

Caron is a mural artist. Her current canvas is two perpendicular walls of a four-stories-tall office building joined at the corner of Sansome and Green streets in San Francisco’s Telegraph Hill neighborhood. Double-decker tour buses rumble by on their way to Coit Tower. From up here, she can see the glittering Bay to the east and the Transamerica building to the south. In the late afternoon, she says, when it’s actually quiet, the famous green parrots of Telegraph Hill fly overhead.

The plant unfolding on the walls in front of her is a Plantago lanceolata, or ribwort plantain, a scraggly weed she found sprouting by the curb down below. In mural form now, it’s growing—like a scene from some kind of science fiction movie—to roughly 40 times its actual size. This is part of Caron’s latest project—painting diminutive weeds very large. She’ll choose a wild plant that no one pays attention to and then paint a towering heroic version right next to the real thing—forcing onlookers to see what they might otherwise have stepped on.

“It’s like appreciating things that are outside the gilded frame, that are outside the spotlight,” says Caron. “Because any little bit of nature is actually beautiful if you take the time to look at it.”

Right now, while balancing her weight and nimbly brushing strokes of dark green onto the bumpy beige surface of the wall, she wagers she’s about the size of a bee next to the enormity of the plant she’s created. She often imagines what kind of insect she would be while she works. Sometimes she’s a butterfly. Other times, like while painting a 13-stories-tall Achyranthes aspera in Sao Paulo, Brazil last year, she was no larger than an aphid.

Caron was born and raised in Ticino (the Italian speaking region of Switzerland), speaks seven languages, and moved to San Francisco as an artist in her 20s. She’s been painting large murals here in the Bay Area and all over the world for almost two decades now.

But her current subject matter—and its inverted proportions—reminds her of how she used to entertain herself as a child growing up in Switzerland. She didn’t have a TV so she would lay on the ground and imagine herself as a bug looking up at plants from below. From that vantage point she could marvel at the soaring height of a simple clover leaf.

She comes by this appreciation naturally. Her grandfather was a botanical illustrator, who, according to Caron, knew all the wild plants of Switzerland by Latin and common name. And her mother passed that love and knowledge on to Caron and her sister, who’s now a chef writing books about how to cook with weeds.

As a muralist though, Caron is most well known for her narrative and political works that employ birds-eye perspectives on cityscapes and the people in them. One of these is “Windows into the Tenderloin” — a multi-panel set of vignettes at Jones and Golden Gate in the Tenderloin area of San Francisco. It chronicles daily life in the neighborhood and envisions a future for its residents. Working with the neighbors day in and day out was a collaborative and rigorous process for Caron, one she’s proud of. But she wanted a break from weaving so many people’s narratives into her work. She wanted to find something more distilled and poetic that would continue to shine a light on the resilience of what survives at the margins of society.

She turned to weeds—the scraggly vegetation that sprouts unbidden and untended from cracks in the sidewalk. Caron says weeds have actually been in her artwork all along. They were there (larger than life even) in the background of her very first mural. What changed is that they grew larger and eventually took center stage. And now her creed is, “the less attention we pay it, the larger I’m gonna paint it.” She’ll travel to a site, find a weed nearby—a dandelion, a stinging nettle, a lowly swine cress, sometimes something so overlooked and anonymous that she never even finds out its name—and she’ll say “Ok, you’re the one. You’re the one who’s gonna be seven stories tall.”

It’s not lost on Caron that the word “weed” is derogatory, that people spend time, energy, and resources trying to eradicate “weeds” from places where they weren’t planted. It’s also not lost on her that many of these plants have edible and medicinal value for people, and even an ecological role to play. But she’s emphatic that her murals are not an endorsement of invasive species over native ones. She intentionally uses the word “weed” and the images of these plants provocatively. What she tries to highlight is “the transgressive act of bringing life back to something that seemed to be dead.” Concrete jungles, superfund sites, urban slums — are typical of the kind of landscape Caron chooses to grow her weed murals.

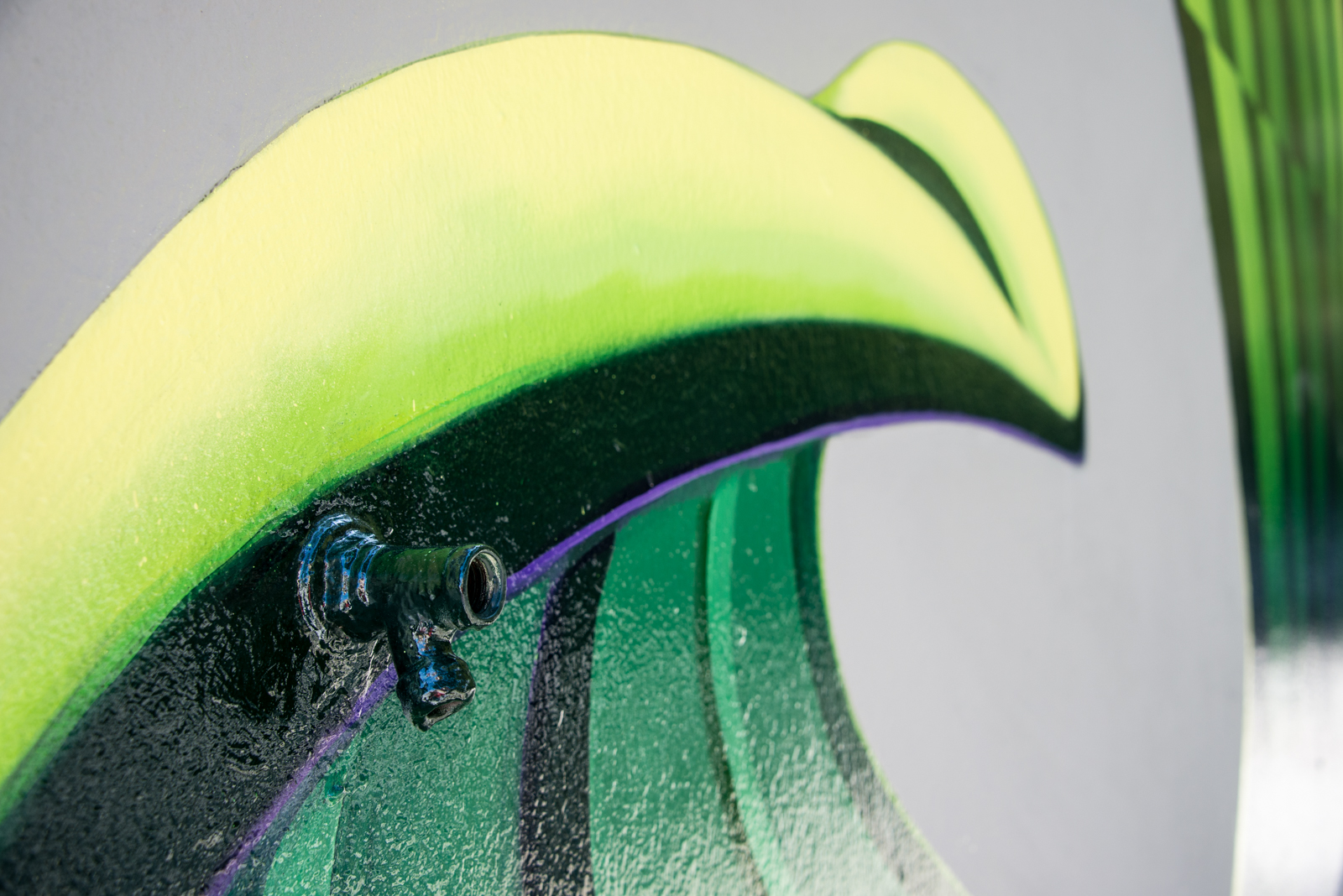

She insists she’s not a botanical illustrator. When admirers tell Caron her plants look realistic, she points out that they’re really not. She starts with inspiration from photographs, but uses her artistic license to make her representations much more graphic and bold. She wants her plants to appear muscular and imposing, rather than dainty, pretty, or even scientifically accurate. “These are plants that have power. That is intentional and it works within my metaphor.”

The metaphor of outcasts taking center stage has been the through-line of Caron’s work. Instead of painting portraits of heroic leaders, in her narrative murals about the city, she focused on the collective power of everyday people doing everyday things. She has the same kind of appreciation for weeds. “You may not pay attention to them, but they break through the hardest concrete.”

Word got out about her project back in 2014 after Caron produced a short video and posted it to the internet. The wordless film shows her weed paintings set to music, animated through stop motion, sprouting and climbing and blooming on their own along rooftops, on the sides of buildings, over and through existing graffiti and along the edges of highways. “On rooftops with the whole cityscape at their feet, these little plants were growing gargoyle-like,” she recalls, “looking over the city as if something big was about to happen and nobody’s paying attention.”

But people were paying attention. Like a dandelion dispersing its seeds, the video went viral. And Caron started getting calls. Just like the weeds themselves, she notices, her idea seems to have no borders. Weeds have spread because of globalization. Similarly the concept of weeds symbolizing resilience and resistance takes hold wherever she paints a new mural, in part, she thinks, because a visual metaphor doesn’t require language to understand it.

In the last few years, she’s received invitations from Brazil to India to Spain to paint weeds on mosques, community centers, art galleries, anarchist collectives, and even private homes and commercial spaces. “I often feel that artists are like radio towers detecting a lot of the ideas that are out there,” she says. “I try to make visual representations of these alternatives.”

At the corner of Sansome and Green, Caron’s ribwort plantain is becoming its own towering reality. It’s formidable and exultant with long lance-shaped leaves that span across two walls, wrapping around the building’s northeast corner. The triangle-shaped flower head points to the sky, echoing (even—from some angles—rivaling) the tapered tip of the Transamerica building in the background.

The symbolism is especially potent in San Francisco, she says. To paint a giant weed rivaling one of the Financial District’s iconic landmarks is a protest against what Caron refers to as increasing gentrification and capitalism in the Bay Area. She laments the fact that every square foot of ground is bought up and used for profit, leaving little room at the margins for artistic expression or spontaneity. “For people who are creative,” she says, “this whole situation feels like a chokehold.”

So the power of a giant weed is “reclaiming that space, asking for a little crack somewhere where we can still thrive. And I think we will,” she says. “We are going to find those cracks someplace.”

People often pass by and say, “Wow, what is that amazing plant? Is that some kind of orchid or something incredible?”

“No,” she replies. “You just stepped on it.”

Ali Budner is a writer and radio producer based in Oakland. She’s also a plant nerd and is trained as a western herbalist.