All illustrations courtesy Nature in the City Map. Purchase a copy here to help support Nature in the City’s mission of eco-literacy, stewardship and restoration in San Francisco.

San Francisco, judged in the usual way, is a pretty unnatural place. Out of the dunes and scrub, humans have raised some 49 square miles of concrete and asphalt, timber and steel. But even for such a built place, is “unnatural” really the right word? Most boundaries between human and nonhuman start to seem pretty sloppy when you really look at them—take, for example, my apartment, which I co-occupy with 13 plants of various species, sugar ants, fruit flies, spiders, at least three types of moth, and one synergistic colony of fungi and bacteria that I occasionally pull out of the fridge and use to leaven waffles. Even the organisms I invited into this space are only nominally under my control. Our shared space definitely isn’t “natural,” but it’s not completely unnatural, either.

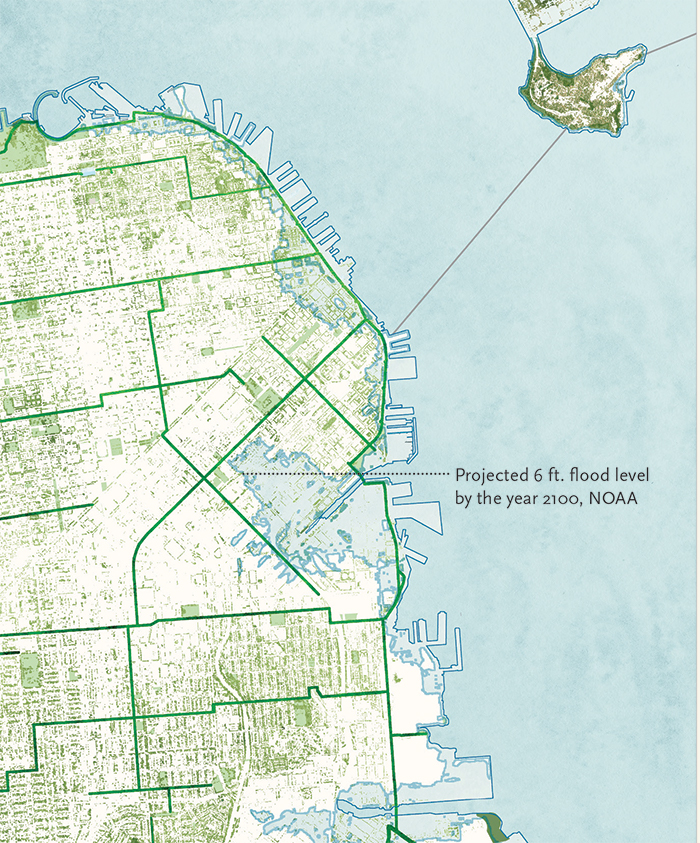

This pleasant sloppiness, basically, is the idea behind a newly released map of San Francisco. The map was put together by a collection of humans—including writer Mary Ellen Hannibal and graphic designer Leah Elamin—employed by and volunteering for the nonprofit Nature in the City, the Presidio Trust, the California Academy of Sciences, the Exploratorium, and various branches of the city government and is called, simply, “Nature in the City.” The front side of the map shows a standard street map of San Francisco overlaid with a dusting of street trees and shaded spots that represent its former shoreline, with scattered illustrations of animals and plants (rendered in loving detail by artist Jane Kim). The back of the map contains four smaller maps: one that shows the city’s waterways, soil types, and geological formations; one that highlights its public gardens; one that shows the migration routes of various animals across the Bay Area and beyond; and one that shows the location of native plant nurseries and the effects of projected sea level rise.

Together, the five maps are meant to encourage city dwellers to see nature as something that can be found right in their neighborhoods, says Amber Hasselbring, Nature in the City’s executive director. It’s a broad survey of the natural world and one that creators hope will leave viewers wanting to know more: “It’s a tool that invites more inquiry,” she says.

On a rainy day in January, I walked across San Francisco, looking for nature in all its forms. I confess—I didn’t have the map with me. That’s because it was raining, and it would’ve turned to mush. It was fine, though. Physical navigation isn’t really what the map is for, anyway. There was debate among the mapmakers about whether the map should be a navigational tool, says Peter Brastow, Nature in the City’s founder and now biodiversity coordinator in the city’s Department of the Environment, but in the end most of the mapmakers agreed people would rather use the GPS on their phones for getting around. “There was a very strong feeling that it’s not a way-finding device,” he says. “It’s an inspiration device.”

»THE ONCE AND FUTURE SHORE

I set out from the Ferry Building, accompanied by Rebecca Johnson, of the California Academy of Sciences, and Bay Nature editorial director Eric Simons. Walking south along the waterfront, we immediately spot a seal, some pigeons, gulls, a row of palm trees, and what Simons tells me is a water gum tree, Tristaniopsis laurina. As Johnson says, learning new species is like learning a new word—“suddenly you see it all the time.” It’s true. The things are everywhere.

We follow the shoreline south to Mission Creek. The front side of the map shows the shoreline as it existed in the early 1800s. Compared to the shoreline of today, hard-edged as a Lego set, the historical shoreline was wavy and uneven, cutting deep into the current South of Market, Marina, Dogpatch, and Financial District neighborhoods. Lindsay Irving, a freelance data visualization consultant and the map team’s project manager and cartographer, says the historical map data was provided by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, which in turn got its information from old documents and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration surveys.

The map also offers a glimpse of the possible future. One of the mini-maps, built using sea-level rise projections from NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer,, shows the shoreline of 2100. “Ironically, the historical shoreline mirrors what the future projected flood zone would be at the end of the century,” Irving says. “Water has a great memory.” She hopes that when people look at the map’s past and present shorelines, they’ll think long-term thoughts about “how time exists on the landscape.” San Francisco spent the last 150 years expanding out into the Bay, but it seems that Nature—which I use here in the John Muirian, animist sense of the word—will eventually take back what is hers.

»TREES AND THEIR NEIGHBORS

Johnson, Simons, and I trace the (now mostly subterranean) path of Mission Creek southwest to Dolores Park, then veer south through Noe Valley to Billy Goat Hill. There we part ways, and I continue on through the redwoods and brush of Glen Canyon Park, up and down and up and down the grassy and befogged Twin Peaks, then into the towering eucalypt forest/plantation (yes, we hear you) of Mount Sutro. It’s not only the city’s parks that are defined by their trees or lack thereof. One of the key differences between this map and its predecessors from 2005 and 2007 is that this version includes street trees, which appear on the map as a sort of variegated greenish tinge, like lichen on a tree trunk. Brastow says the mapmakers chose to include the layer to better illustrate just how close nature is to all the city’s residents, so everyone can look at the map and say, “There’s some degree of nature just down the street from me,’” he says. Very often, that degree is a tree.

Some parts of the city, as the map clearly shows, have far fewer street trees than others. South of Market and the Sunset are particularly bald. Compared to other large American cities, San Francisco as a whole has a sparse urban forest, with less than 14 percent of the city shaded by trees, compared to 24 percent of New York City and 30 percent of Portland. There’s room for more, though. According to a survey published in 2014, the city currently has about 105,000 street trees and vacant spots for as many as 100,000. But should we really be planting more street trees? As many have pointed out—especially in arguing for the removal of certain Australian blue gum eucalyptus forest/plantations—prior to European settlement, the San Francisco Peninsula had hardly any trees.

But Doug Wildman, deputy executive director of the nonprofit Friends of the Urban Forest, which helped conduct the street tree survey, says this concern isn’t really relevant. Street trees reduce cooling costs in adjacent buildings, soak up storm water runoff, and absorb pollution. He points to studies that show that where there are trees, there is less crime, as well as slower traffic and healthier people. “It’s the environmental and psychological and physical benefits they provide,” he says.

There are discussions of natural and unnatural, and then there’s the fact that life is just better with trees. Call it human nature.

»A HAIRSTREAK STREAK

I descend from Mount Sutro through the Forest Hill neighborhood. I pass Hawk Hill, which is marked on the map as part of the “Green Hairstreak Corridor.” The corridor is something of a pet project for Nature in the City and a tie to the way San Francisco once was. The butterflies are residents of coastal sand dunes, says Hasselbring. Over the years, as the dunes covering much of San Francisco were converted into human habitat, the butterfly’s range in the city dwindled to the dunes above the Presidio’s beaches and to two small patches in Golden Gate Heights. The latter two locations are only 10 blocks apart, but even that distance is too much for the butterflies, which, Hasselbring says, are “bright iridescent green, the size of a nickel, and almost invisible unless you know what you’re looking for.” The tiny populations seemed like they could disappear at any time.

In 2006, working with lepidopterist Liam O’Brien and the help of volunteers, Nature in the City began re-creating patches of sand dune flora. They ripped out nonnative grasses, ice plant, oxalis, and in their place planted coast buckwheat, seaside daisy, dune strawberry, and dune knotweed, creating a little constellation of butterfly habitat, each near enough to its neighbors for the butterflies to find. The patches don’t always look like much, Hasselbring says—scrubby sections along stairways and in street medians.

If you didn’t know what you were looking for, you probably wouldn’t even notice them.

»THE GREAT FROG RESCUE

Eventually I arrive at Golden Gate Park and head west. I pass South Lake, one of ten lakes in the park. Some of these lakes are human-made, others not. All are infested with the likes of crayfish, red-eared slider turtles, mosquito fish, or some combination thereof. People introduced these creatures as a way to improve the lakes. But ideas about what nature should look like change. Now, many people would rather the lakes held chorus frogs. The mapmakers included an illustration and side panel information about the diminutive tree frogs for the simple reason that, as Brastow says, “it’s an amazing story.”

Once, Pacific chorus frogs were common in the city. In 1928, a herpetologist found them in both Golden Gate Park and the Presidio, but in 1966, another herpetologist judged them to be “reduced or nearly exterminated.” By the late 1990s, according to local lore, the last of the city’s chorus frogs were holed up in a small pool of water that collected at the base of Potrero Hill. The pool was hemmed in on the downhill side by a construction site and on the uphill side by an invasive grass, which threatened to shade out the pool, rendering it useless to the frogs. But there was a man who really loved Pacific chorus frogs*, and instead of letting them die out, he gathered up their eggs and carried them in secret to lakes and ponds in Golden Gate Park and in the Presidio.

“These frogs just showed up,” says Jonathan Young, a wildlife ecologist with the Presidio Trust. As a graduate student, he helped the frogs spread out from a small seasonal pool in the Presidio, which, it so happens, was the only place the rescued frogs were thought to have survived.

But moving the frogs farther turned out to be difficult. Like the lakes in Golden Gate Park, most of the Presidio’s lakes and ponds were infested with frog-eating fish. Young was also worried about spreading the deadly chitrid fungus—currently decimating amphibians worldwide—to terrestrial salamanders. He devised a type of floating egg carton, to keep the frog eggs safe from hungry dragonfly larvae and crayfish. Now, after years of work, “the chorus frog in the Presidio is doing pretty well,” he says, especially compared to its prospects in the rest of the city. But even in the Presidio, the frog’s long-term survival is likely dependent on sustained human attention. “You have to manage and maintain this kind of habitat,” he says of the rehabbed lakes. The Pacific chorus frog in San Francisco has become something akin to a houseplant or sourdough starter.

But maybe that’s just falling back into the standard trap of what is nature and what isn’t. The line is sloppy and always has been.

The frogs at the Presidio actually weren’t the only population of refugee frogs that survived. Charlotte Hill, then an employee of the educational nonprofit Kids and Parks, helped orchestrate another frog resettlement, into a specially built pond at Visitacion Valley Middle School, in the city’s southeastern corner. The frogs have been there now for more than ten years, successfully reproducing, she says. During the rainy season, you can hear them from a long way away. “Oh, they’re loud; they make a racket,” she says. “People love it.”

»ON WHALES

Finally, in the late afternoon, more than 15 meandering miles from the Ferry Building, I reach Ocean Beach. I cross the line of sea scudge and dried seaweed, pass a graffitied concrete block, and stop at the edge of the waves, looking out at the gray ocean. The map shows a blue whale out there, which surprises me. It seems fantastic, like the monsters old-time cartographers used to fill the space where they weren’t sure of the reality.

Later, I ask Johnson about the whale. She explains that they come to the waters off of Northern California in the spring and summer to feed off of krill and other tiny creatures, which in turn are fed by nutrients carried by an upwelling of cold water from deep in the ocean. Bay Area residents are more likely to see gray whales or humpbacks, she says, but the mapmakers ended up choosing the blue whale because the presence of the world’s biggest creature seemed more likely to surprise people, as it surprised me, for the way it seems to expand the realm of possibilities. The whales, which can be found in all the world’s oceans, also serve to anchor the map. “I like to think of how we’re connected to the rest of the planet through these animals,” Johnson says.

Which, essentially, is the whole point of the Nature in the City map. We build walls to separate the inside from the outside, to separate what is ours from what is not. Here in the city, this collection of many walls, it can sometimes seem like no room remains for anything that isn’t ours. But there is still nature here. Once you know what it looks like, you begin to see it everywhere.