I remember, somewhere in between learning to walk and starting kindergarten, lying on the cool grass in the backyard and watching them. They were the color of animal crackers, blasting past me to land on blades of grass. They seemed to look back through big, doe-like eyes with an attitude of “Catch me if you can!”

Though I didn’t know it then, I was watching skippers. Commonly considered something between a butterfly and a moth, they are diurnal (day-flying) and named for their quick, darting movements. Most have clubbed antenna tips modified into narrow, hooklike projections and lack the wing-coupling structure of most moths. The greatest diversity of species is found in the Neotropics, but they occur worldwide save for New Zealand—more than 3,500 species of skippers in all.

Distinguishing between those species is not easy. When butterfly mania took hold of me decades back I thought I’d never crack the skippers’ code: the creatures are impish, and maddening to learn. But the day came—honestly, after about six years of getting it wrong—when I started to feel confident about anything that landed in front of me. I can even look back on those childhood afternoons and say with reasonable assurance that I was watching fiery skippers (Hylephila phyleus).

Skippers are classified in the order of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), within the family Hesperiidae, which now belongs to the superfamily Papilionoidea, the superfamily of butterflies. (Previously, Hesperiidae was placed in its own superfamily, Hesperiodea.) We have about 30 species of skippers in the Bay Area, each belonging to one of two subfamilies: the spread-wings (Pyrginae) and the branded or grass skippers (Hesperiinae).

That’s about as much taxonomy as I want to get into, because skippers are daunting enough. Now I’m going to give you some advice that I wish someone had given me when I started out: focus on the three most common species. You can find them in just about any park, vacant lot, or natural open space.

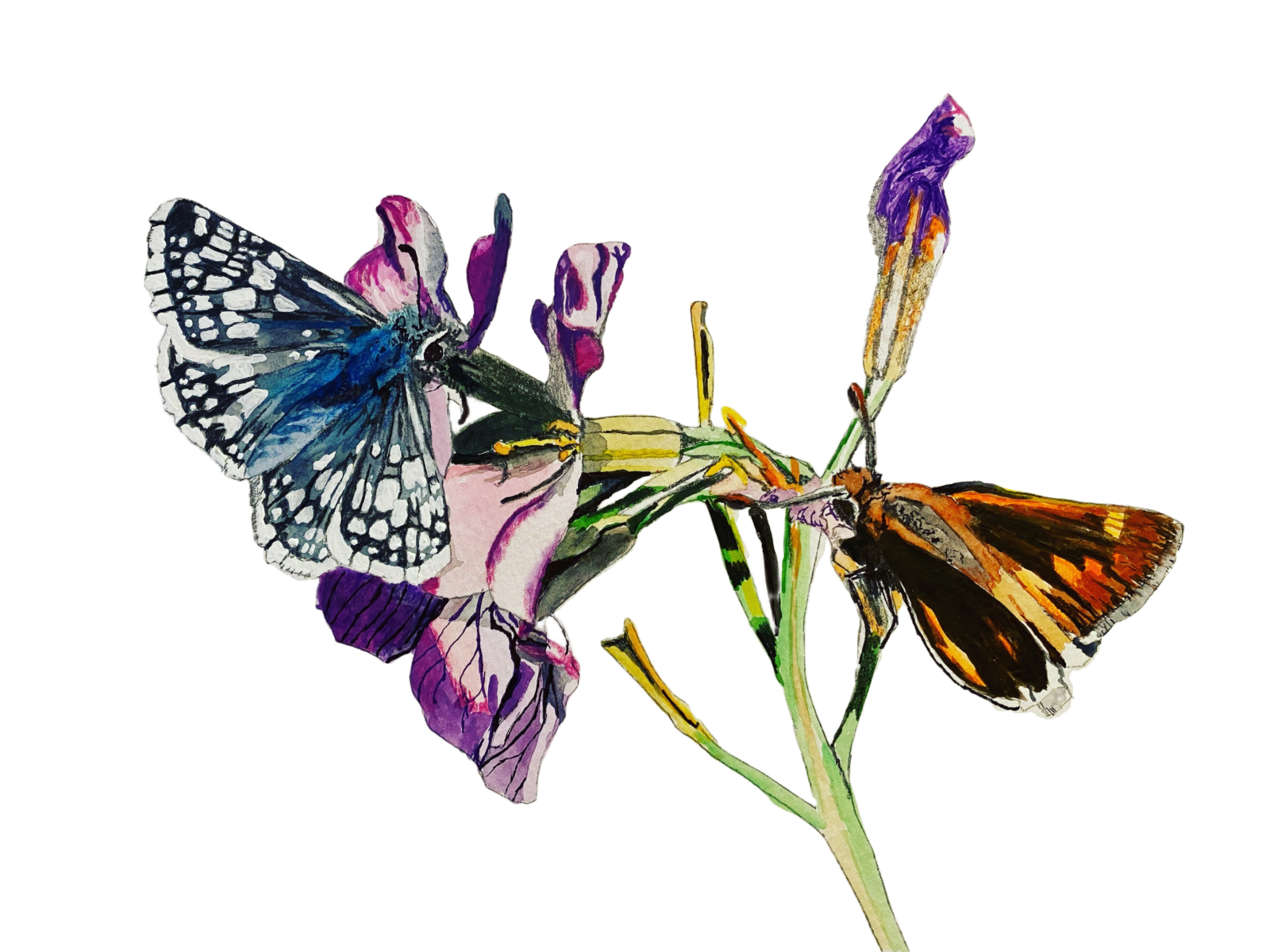

Our most ubiquitous local member of the spread-wing group is the common checkered-skipper(Burnsius communis), which basks in the sun in the mothlike, wings-spread-flat posture of the Pyrginae. The blue hairs on the thorax can cause people to confuse this species with blue Lycaenidae butterflies—occasionally with contentious results. I once got called to Potrero Hill to settle a dispute between a person wanting to build on a vacant lot and a neighbor who insisted she’d seen the federally endangered mission blue butterfly on the property … and didn’t want the proposed building blocking her views. But I knew the city’s mission blues flew only on Twin Peaks, and I had a pretty good idea what the neighbor had actually seen. Sure enough, it took only a few minutes to solve the mystery: the common checkered-skipper darting about did indeed look blue in flight, but its checkerboard pattern set it apart from the mission blue.

Theumber skipper (Lon melane) is a chocolate-brown beauty with golden-yellow spots. It thrives in disturbed habitats, and I’ve most often seen it on blackberry vine blossoms. Like that of other branded or grass skippers, its stance is the “bombardier” position: forewings (or top wings) up and hind wings (or lower wings) out, like a jet sitting on an aircraft carrier. It has an extraordinarily long proboscis. I’ve seen one with a tongue a good two inches long extended into a thistle—amazing, considering how small the creature is.

The third and final species you must learn is the one I started with, the fiery skipper (Hylephila phyleus). This tawny traveler has taken well to breeding on what is loosely termed “the American lawn,” which is really a collection of grasses. When ready to pupate, the caterpillar pulls up blades of grass low to the roots and creates a nest woven together with silk. Some believe this species avoids heavily mowed lawns, but that’s not my experience—in fact, a great place to watch them flitting about is the Great Meadow near the San Francisco Botanical Garden in Golden Gate Park, where you’ll see males jousting one another in aerobatic displays worthy of the Blue Angels.

So, that’s the plan: learn the fiery, the umber, and the common checkered. Become very familiar with them before you move on. The woodland skipper and the dreamy and mournful dusky wings all await you. It’s a niche of Lepidoptera that is all too often dismissed—“Oh, those are just skippers”—but we know better: barnstormers in the miniature, skippers are dazzling aerialists just waiting for the next curious child lying in the grass.

An earlier version of this article was first published by the Golden Gate Audubon Society.