Text and research by Bay Nature staff.

Life during summer … is about arrival from faraway places, weathering challenges, and feasting while you can.

What Comes Around

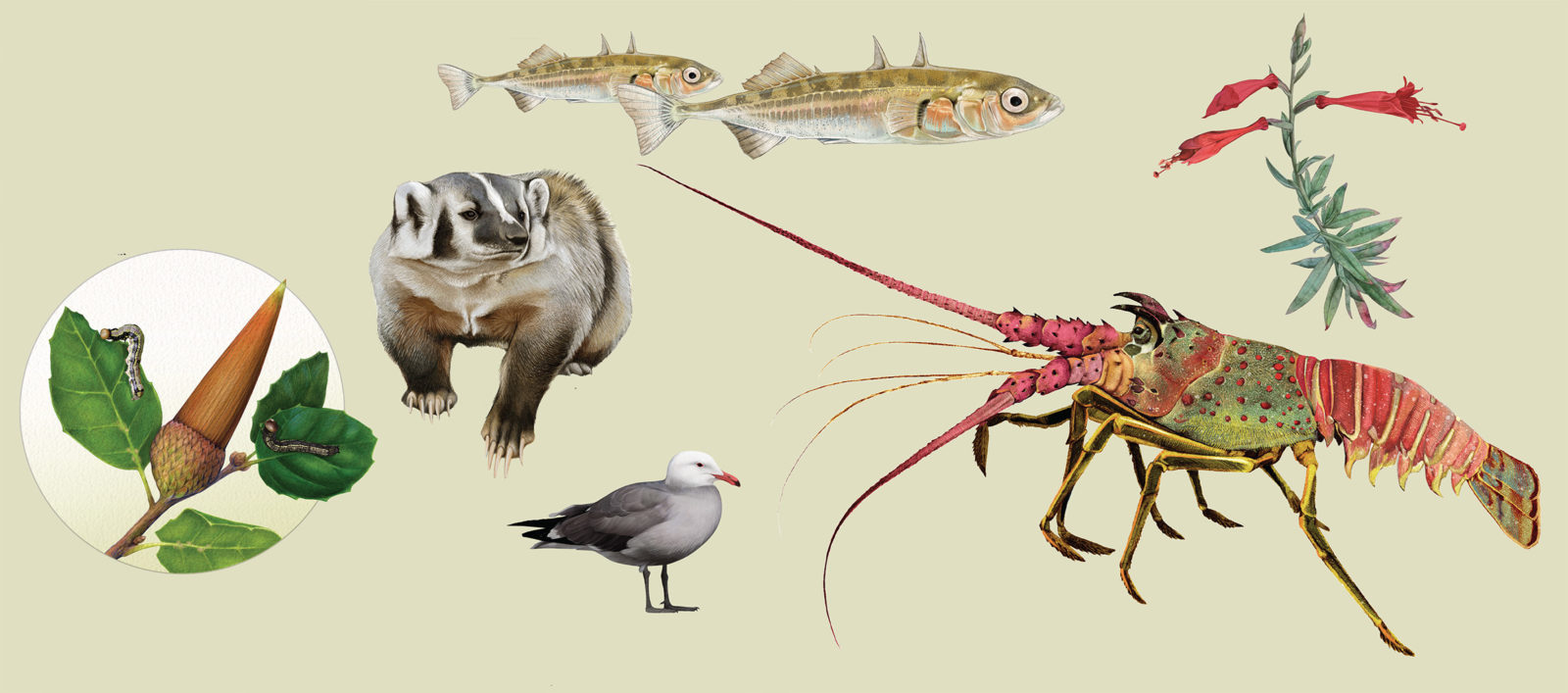

An oak leaf is so much more than just a leaf. It’s a wafer of changing chemistry. In summer when new coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) leaves flush, each is packed with nitrogen and phosphorus. The abundance of those nutrients fades as a leaf ages and its tannins concentrate. Unlike most herbivores, the California oakworm, or oak moth (Phryganidia californica), doesn’t much care. The caterpillar will eat the leaves no matter how old or bitter, and about every five years, it will eat them all, completely defoliating the evergreen tree. In a textbook example of nutrient cycling, as the caterpillars devour the leaves, a light rain of the grub’s nitrogen-packed frass, and even dead bodies, falls from the oak’s branches to the ground, sending an immense pulse of nutrients back into the soil.

See Gulls

Did you know at least 11 species of gulls are found along Bay Area shorelines in summer, according to the San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory? And that if you can’t tell most of them apart, you’re in good company with the overwhelming majority of us? But there is one distinctive species, Heermann’s gull (Larus heermanni), that most of us can learn to recognize. Heermann’ses arrive in the Bay Area in July, having flown from the Gulf of California, where 95 percent of the entire population nests on a quarter-square-mile volcanic rock named Isla Rasa. The birds are devoted to both their nesting island and their summering spots; one Heermann’s reportedly visited the same yacht club in San Rafael for at least 17 summers.

Elusive Badger

Catching sight of an American badger (Taxidea taxus) in the Bay Area is a rarity, but if there’s a time of year these burrow-inhabitants are on the move, it’s summer. Juveniles leave their mother beginning in June and by July it’s mating season for adults. Badger home-range size varies wildly, but one study found 4.5 square miles was average for males near Monterey, and another study stated that the polygamous fellows will expand “their home ranges by as much as two to three times” while looking for mates. Badgers, a species of special concern in California, are increasingly studied as a proxy for grassland conservation.

Natural Selection

Summer in the Bay Area is tough on a lot of water-loving species. Seasonal creeks dry to puddles; estuaries get cut off from the ocean; water becomes warmer, saltier, and less oxygenated. But weathering these extreme and increasingly common conditions is the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), a storied species known for its capacity to adapt. And they are adapting. Bay Area sticklebacks now resemble Southern California sticklebacks, accustomed to a drier and warmer climate, according to UC Santa Cruz professor Eric Palkovacs. “They’re evolving every summer to look progressively more like their Southern California cousins.”

Summer Snacks

After so much has dried out on chaparral hillsides in late summer, the California fuchsia (Epilobium canum) blooms its bright red flowers, each shrub a corner store for pollinators and other insects. “It may be a really important keystone plant species,” says UC Davis professor Rachel Lee Vannette, whose students have collected data on the fuchsia for years. They’ve found that hummingbirds seek out the tallest, reddest flowers. Chubby carpenter bees cut open the narrow tube of petals to access the nectar, a slit that other bee species then use. Small native bees collect the unusually sticky pollen, while some moth larvae love to eat the anthers. And a stilt bug lives on seemingly every flower, sucking up its plant juice.

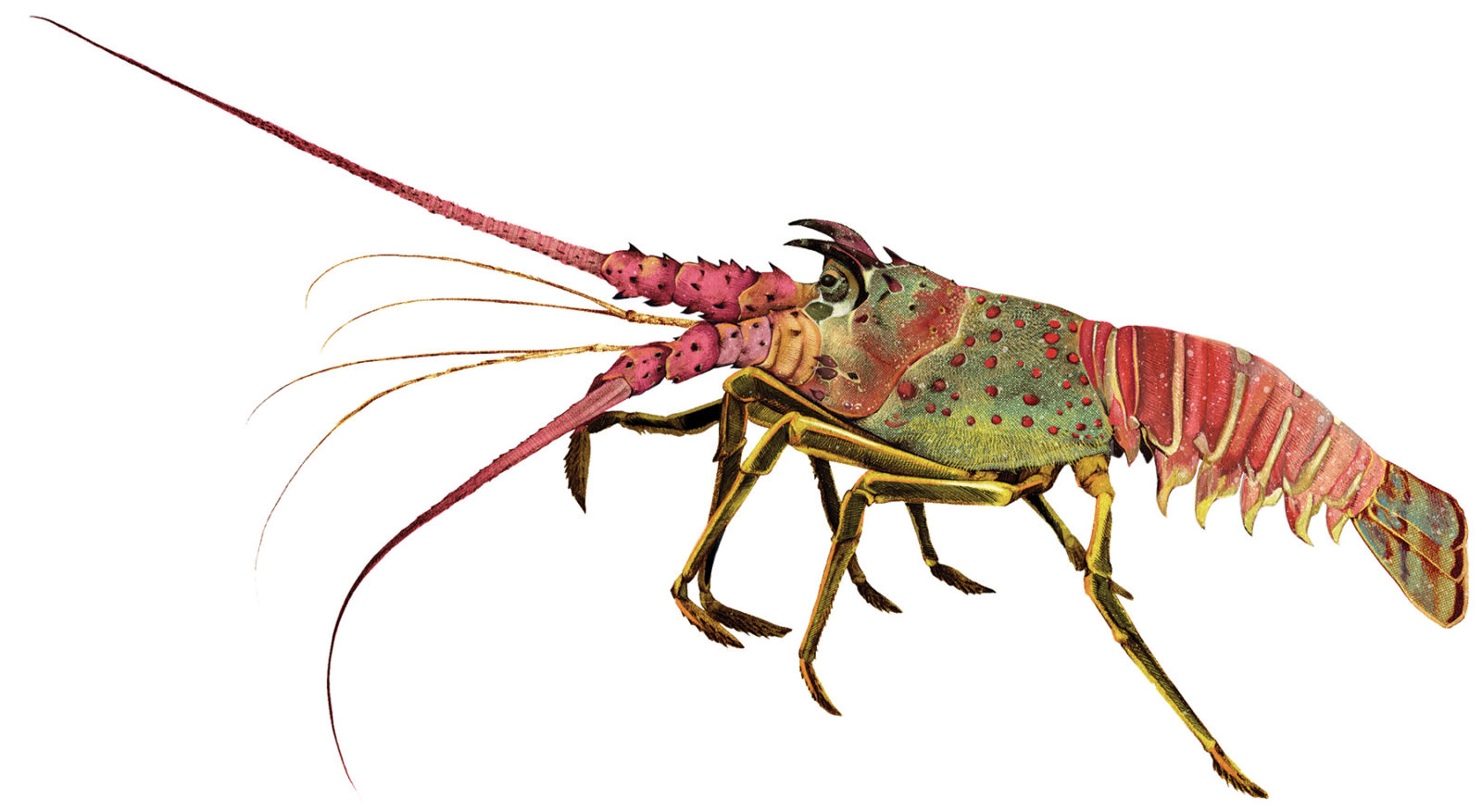

Signs from the Deep

California spiny lobsters (Panulirus interruptus) march from the deep coastal waters where they spend most of their time to the shallower and warmer tidal areas between June and September as their 50,000 to 800,000 eggs hatch. You won’t see the microscopic larvae, but you may see the female molts—which pretty much look like lobsters split open across the curved back—that wash onto shore in summer. Spiny lobsters have moved north from Central California over the last decade due to changing ocean conditions and warming waters and these days can be found as far north as Duxbury Reef in Marin County.