Words by Bay Nature staff; illustrations by Jane Kim.

An ephemeral amphibian

From an egg sac secured to a shoot of vegetation in a natal pond, a California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense) wriggles free, and its race against evaporation begins: the rains end; the ephemeral pond shrinks; the spring sun beats down. The little larva snakes a finned tail to swim the pond, lunging at zooplankton, maturing to hunt tadpoles and other salamander larvae. It hides from hungry frogs and breathes through feathery gills. If it grows a pair of lungs and completes metamorphosis before the pond disappears, it may live for a decade or more, mostly on land.

A sensitive bush

This spring, you will see the sticky monkey-flower (Diplacus aurantiacus). If you go outside, on a trail for example, it’s practically guaranteed. This native shrub grows in most Bay Area habitats. When you peer into the face of the penny-size monkey-flower, look for the whitish stem (the stigma) protruding from its center with two tiny lobes. Touch it with a twig, and it will gently close. The flower thinks you’re a pollinator bringing the pollen goods, its next generation.

Where the antlers go

North American porcupines, western gray squirrels, California pocket mice, and many, many more Bay Area rodents eat the antlers left by tule elk and deer (Cervidae), as well as their bones. It’s a beautiful-to-some picture of nutrients moving through a landscape. After an elk sheds them during the shortest days of the year, the antlers are sources of calcium and phosphorus. Rodents gnaw them for the nutrients and to grind down their forever-growing teeth. While out and about this spring, look for antlers with telltale gnaw-marks, and then leave them for the other mammals.

Not a cat

Also not a fox. Or a raccoon. Or a weasel. Meet the ringtail cat (Bassariscus astutus), a raccoon relative that measures about two and a half feet long, half of which is bushy tail, and weighs maybe two to three pounds. A nocturnal carnivore, this not-cat also likes a good acorn. It climbs trees and it dens with its young in rocky crevices and tree hollows in spring. It may be the cutest Bay Area mammal that you’ll likely never lay eyes on. But maybe it’s enough just to know it is here.

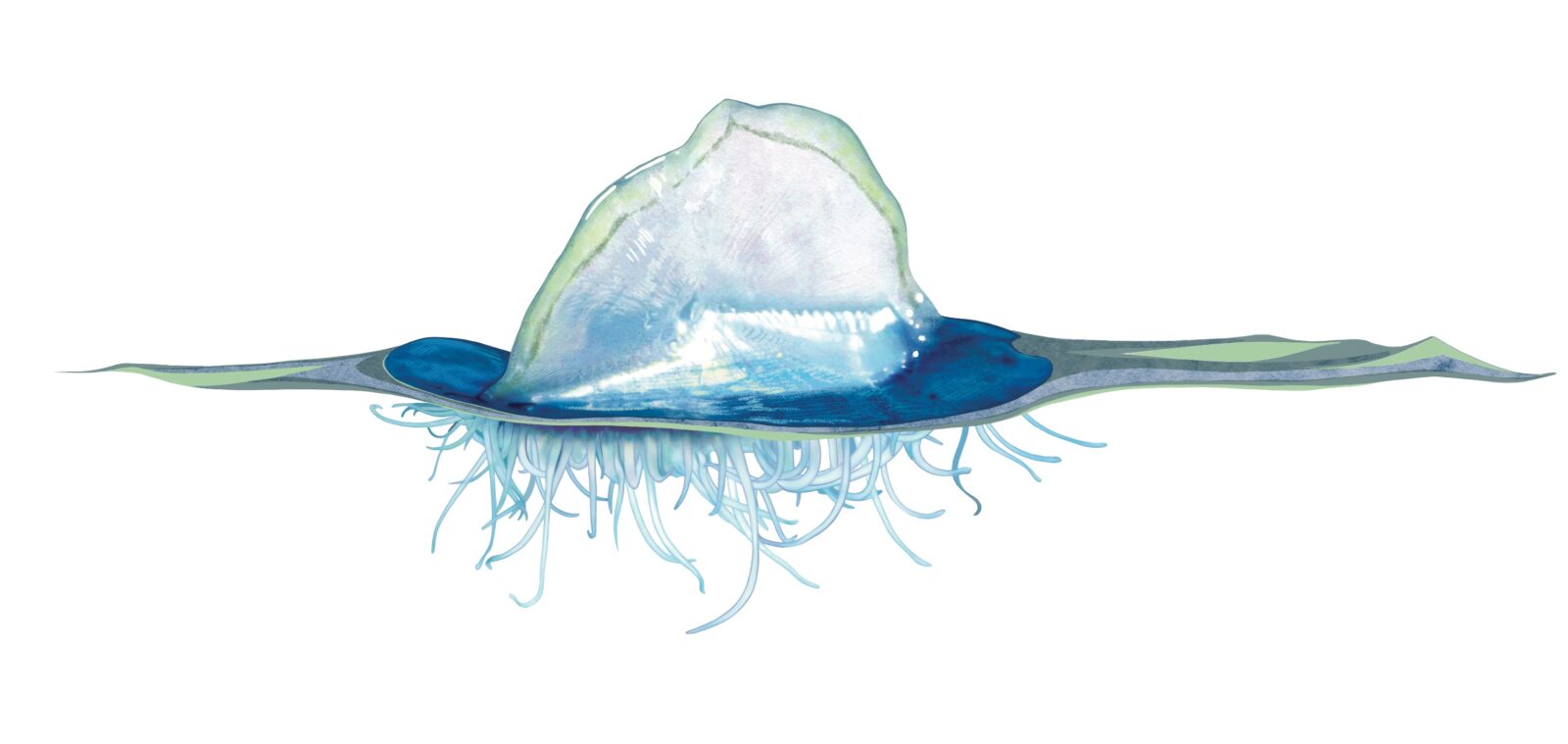

Lovely drifter

The ocean’s surface is a habitat and structure unto itself. Take the non-stinging jellyfish cousin called by-the-wind sailor (Velella velella), which floats on top of the sea, turned facedown into a saltwater world. Its short blue tentacles and mouth seek out zooplankton just below it, as though the sea’s depths were the sailor’s sky. On its backside, a chitinous sail sticks up an inch or two into the air, helping it drift in temperate and tropical waters worldwide. A strong onshore wind, like those we get in spring, can push huge numbers of these beautiful blue sailors ashore, where their travels end.

La commune et les artistes

If nests are sculptures, bushtits (Psaltriparus minimus) weave the Rodins of avian homes. Their bold, ruggedly organic, sometimes bronzy brown, oblong masses can hang down a foot from branches. A hole at the top lets the nesting pair and their many attendants squeeze in and incubate a handful of small white eggs. Various bushtits from the flock get involved in all sorts of ways—weaving, feeding, mating, and fighting, a birdy rendition of the Monument to Balzac.