Text and Research by Bay Nature staff

Never Underestimate a Squirrel

You might think small, furry California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi) would be defenseless against rattlesnakes, one of the many species that take refuge in ground squirrels’ burrows during the hot summer—and one of their primary predators. But you’d be fantastically wrong. Ground squirrels have so many tricks up their metaphorical sleeves, there may not be room to list them all here. They chew up skin shed by rattlesnakes and then lick themselves to mask their odor. They chatter furiously, wave their tails, and kick soil on a snake, sometimes to provoke and assess the predator. Based on the sound of the rattle, they can gauge the size and dangerousness of an individual snake. Ground squirrel tails also possess a silent superpower: In the presence of a rattlesnake (but not, for example, a garter snake), the ground squirrel’s flagging tail heats up, emitting infrared radiation that rattlesnakes sense, deterring their attack. And if all these tactics fail and an individual gets bitten, it may still survive. After many millennia of this dance, adult California ground squirrels have become largely resistant to rattlesnake venom.

Bear Culture

Black bears (Ursus americanus) have expanded out of the forests of Northern California and into the region’s oak woodlands, now living in parts of the Bay Area—specifically, Sonoma and Napa counties—in increasing numbers. In summer they feed on manzanita berries, new shoots, and insects. They also frequently communicate with one another by clawing and biting trees; they favor the fragrant Sargent cypress, according to environmental educator Meghan Walla-Murphy. She leads the North Bay Bear Collaborative, a new group that aims to study the regional population and educate the public about living with bears.

Measuring Drought

Drought conditions in the Bay Area, where rainfall in some areas is at roughly 50

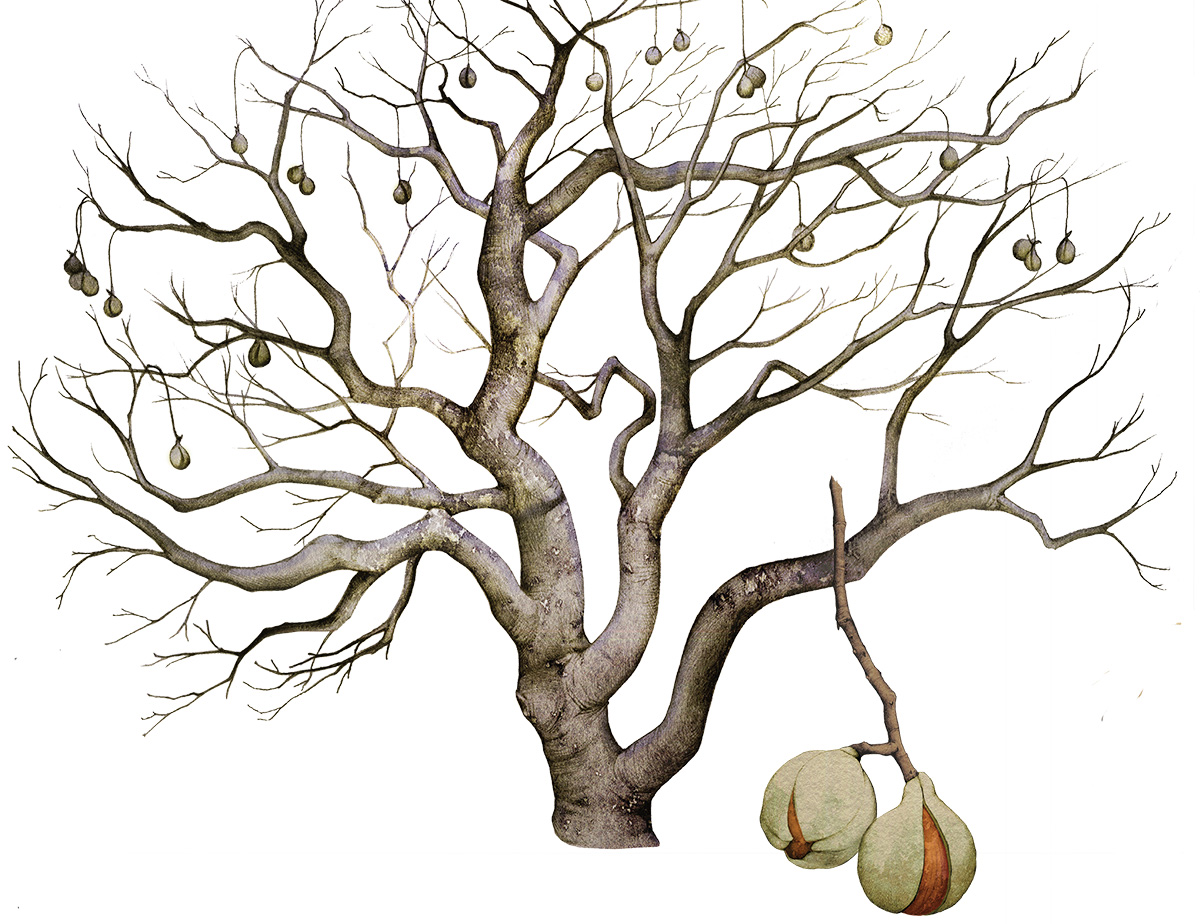

percent of average, are felt first by plants. Our storage reservoirs may be relatively full, but many watersheds have barely had time to replenish since the last drought’s end in 2017. One study estimated the Russian River Watershed would need up to three years for the soil to recover. All this means the California buckeye (Aesculus californica) will be a worthwhile tree to watch this summer. The endemic buckeye grows its large, floppy-fingered leaves during our wet winter. Then, if it has no access to water as the long, dry summer sets in, it drops them to reduce its need for moisture. How early will the buckeyes let go of their leaves this year?

Cooler Without Leaves

You’ll know when you’ve stumbled across a California buckeye in summer because bare of leaves, the tree’s smooth gray branches and branchlets stretch up and out like coralline fingers. Hanging from them are large, round fruits, ornament-like orbs bedecking the tree. In the Bay Area, they start to drop to the ground as early as August; inside the fruits are mahogany-brown seeds with the markings of a buck’s eye. They’re poisonous—as are the tree’s leaves, flowers, and shoots—and have been traditionally used by various California tribes to stun and catch fish.

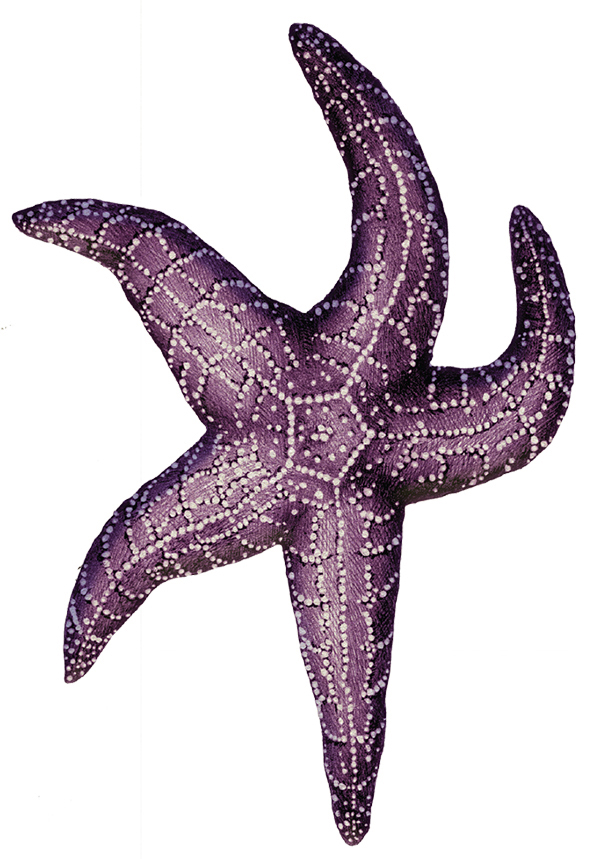

Pisaster Disaster

You may remember the news about a sea star wasting syndrome outbreak that decimated the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus), a common and important inhabitant of tidepools along the West Coast, beginning around 2013. The cause of SSWS remains murky, but it’s likely either a virus or multiple viruses, potentially combined with environmental factors. If you tidepool in Bay Area counties this summer, look for ochre sea stars stalking their pools and clinging to rocky crevasses. Despite the ongoing presence of SSWS, and after several years of extirpation from the Bay Area, the ochre sea star is recovering here.

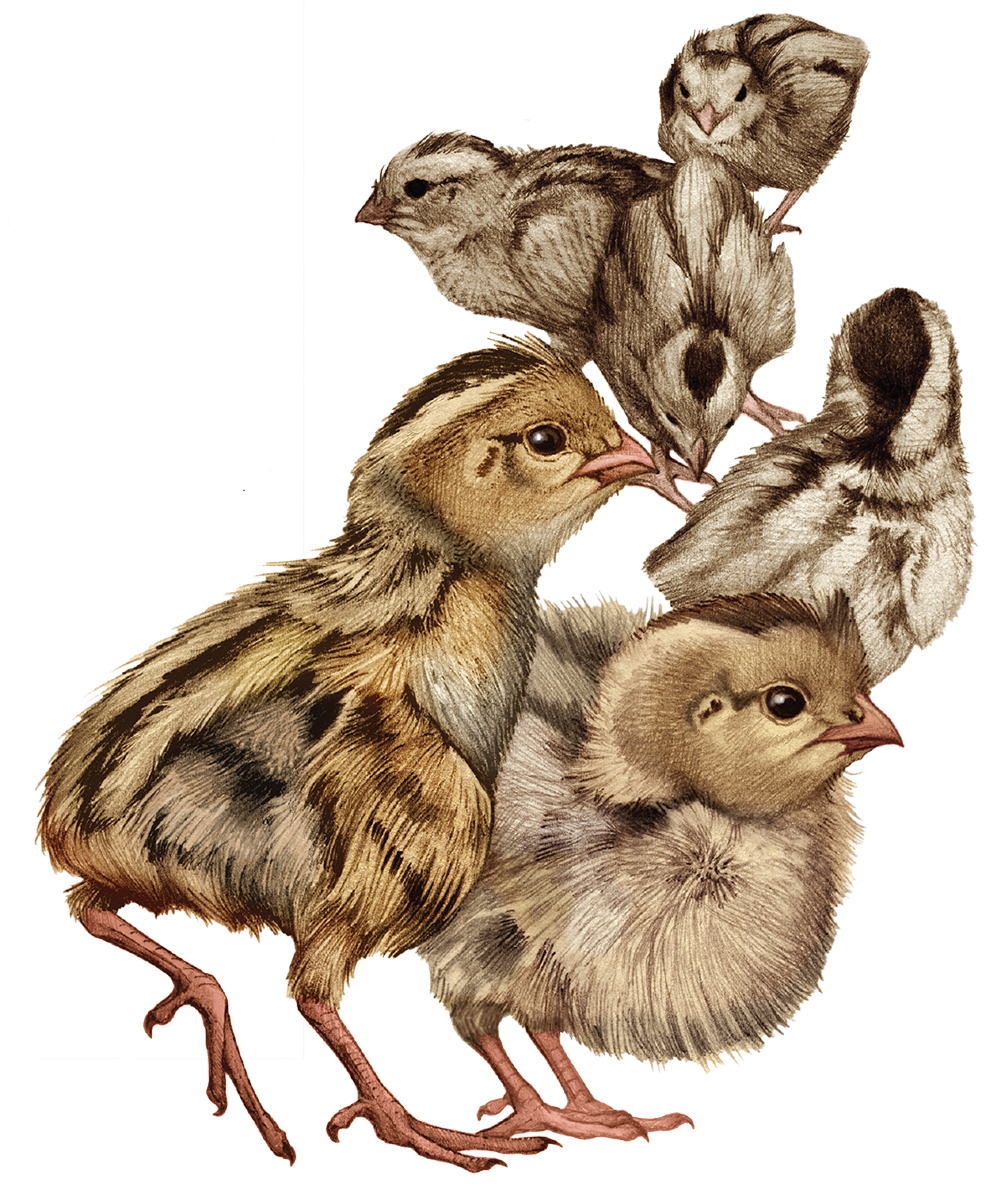

Callipepla

Quails get all the good words. They travel as a covey and are flushed from vegetation into flight. And in the case of the California quail (Callipepla californica), their lovely genus name means “beautiful coat,” after striking plumage that’s capped by the jiggly topknot on their heads, formed of six delicate feathers. Summer’s a fun time to look for our state bird, since you’ll often also find chicks skittering after adults. A rout of quail is a mix of related and sometimes unrelated families, who together raise the chicks.