A duck hunter’s pickup truck rolls up to the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area check station, freshly hunted waterfowl tied into a strap lying in the bed. It’s the first day of duck hunting season in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. Golden and green marsh grasses sway on the flat landscape beneath a cloudy sky.

“Do you mind if I swab your birds?” asks Rebecca Mihalco, a biologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

The hunter consents. He passes Mihalco the nylon strap that carries his take for the day, five ducks of various species, heads tucked through the strap loops. She sets the strap onto her table to identify the birds. To meet the testing quota, she is looking for mallards, pintails, northern shovelers, cinnamon teals, green-winged teals, American wigeons, wood ducks, and gadwalls.

Donning black nitrile gloves, Mihalco grabs a swab on a stick, similar to those used in COVID-19 rapid tests. She opens the beak of the first duck, swipes the inside of its mouth, and drops the swab into a test tube. She swirls another swab in the duck’s cloaca, the birds’ common opening for waste, and drops it into the same tube. After repeating the oral and cloacal swabs for each bird, she returns the waterfowl to the hunter.

By the time the clouds have cleared and the afternoon sun glimmers on the Delta’s tangled channels and marshland, Mihalco has gathered samples from 134 birds, her quota of healthy waterfowl species known to carry avian influenza within the San Francisco Bay watershed. Tomorrow she will be off to the next waterfowl hunting site to do it all again, adding data to the National Disease Program survey of the latest strain of avian flu in wild birds.

Mihalco will deliver her samples to UC Davis, where lab personnel will test them first for avian flu in general and ultimately for the specific strain known as Goose/Guangdong (Gs/GD) lineage highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Gs/GD HPAI is the deadliest and most infectious bird flu ever to strike Europe or North America, according to wildlife epidemiologists. The strain ravages domestic poultry flocks and can sicken and kill more species of wild birds across a greater geographic area than any previous outbreak, leaving an unprecedented trail of death. So far, the virus has affected more than 52 million domestic poultry birds in the U.S. and has been tested for and confirmed in 4,362 wild birds across the country.

If any of Mihalco’s samples test positive, they will go on to the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa, an arm of the USDA. In major waterfowl hunting locations throughout the nation, researchers from APHIS like Mihalco will be swabbing waterfowl as part of a surveillance method known as hunter-harvested sampling. These samples from species of wild birds found to carry the virus will help track its spread and any mutations along the way.

Six million waterfowl traveling south on the Pacific Flyway pass through the Delta in fall and winter each year, with both susceptible and carrier species arriving in the state to overwinter. Waterfowl that have been in close contact, sharing water and potentially viruses with each other, can spread Gs/GD HPAI to new victims.

“The birds are coming, whether we want them here or not,” says Krysta Rogers, senior environmental scientist at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “There’s very little that we can do to control infection in free-ranging wildlife.”

Bay Area arrival

The official count for wild birds infected by Gs/GD HPAI is likely a vast underestimate. Birds falling ill and dying in the remote wilderness are unlikely to be noticed or tested, and when there is a report, officials typically test only one or two individuals. In part because testing wild birds is expensive: Mihalco’s bird swabs cost between $50 to $150 per test. A positive result gets counted in the APHIS database as a single confirmed case, even if officials witnessed a wild flock with several birds dead or showing telltale neurological symptoms, like swimming or walking in circles, seizures, head tics, or twisted necks. “The confirmed number from testing is not a bird-to-bird parallel,” says Jeffery Sullivan, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who studies the role of waterfowl in avian influenza transmission. “This represents what that viral load is in these wild birds.”

For example, researchers estimated that between 300 and 600 birds were affected at a vulture die-off in Florida, but APHIS only sampled three of them. All the tests came back positive for Gs/GD HPAI, making the official detection count for the event three. “A lot of times, it’s just the tip of the iceberg as far as what we’re able to test,” says Julianna Lenoch, a national coordinator with the USDA APHIS Wildlife Services.

Once they’re showing symptoms, susceptible birds go down quickly. For birds of prey and poultry, Gs/GD HPAI has a 90 to 100 percent fatality rate, and there is no treatment. Infected birds can shed the virus through bodily fluids or excretions, mainly feces, which end up in the water that other birds swim in and drink, infecting them and even some mammals. Meanwhile, raptors and other scavenging species can get sick from eating diseased carcasses. Waterfowl, seabirds, and raptors are susceptible, while songbirds seem mostly unaffected—possibly because they aren’t being exposed or their infections are harder to detect.

As of this publication, Gs/GD HPAI has been confirmed in wild birds in all nine Bay Area counties and 39 counties in California. Bay Area wildlife hospitals are on the front lines, screening incoming birds for symptoms, euthanizing suspected cases, and facing the burden of extreme biosecurity measures to try and keep their patients safe from the virus.

The 155 confirmed wild-bird infections in California were found mostly in Canada geese and white pelicans, as well as turkey vultures, mallard ducks, mute swans, Muscovy ducks, California gulls, wood ducks, red-tailed hawks, black-crowned night herons, great horned owls, Cooper’s hawks, peregrine falcons, a red-shouldered hawk, and an American crow. Wildlife veterinarians worry that the virus might find its way into more vulnerable populations of susceptible species, such as osprey, or endangered bald eagles and California condors. “We have not had any cases of avian influenza in condors, as far as we know,” says Alacia Welch, park ranger and condor program manager at Pinnacles National Park. “However, the threat of it is of concern.”

Origins of a flu

Bird flu is nothing new.

Usually, avian flu viruses multiply and mutate inside species of dabbling ducks without raising too much of a fuss. This results in strains constantly circulating among them, not unlike contagious but mild seasonal colds in humans. But every now and then, a flu virus makes the jump into bird species that have no immunity, such as domestic poultry, and wreaks havoc.

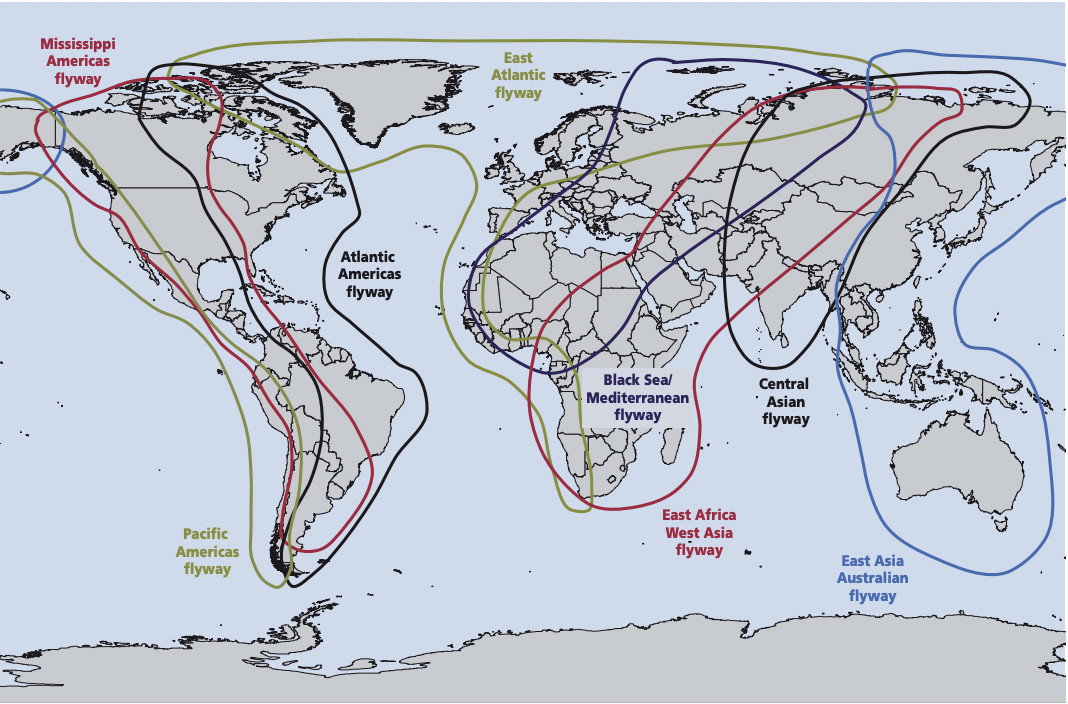

Ducks and other waterfowl that coevolved with avian flu are mostly asymptomatic carriers that can spread the virus as they travel thousands of miles along their migration routes each year. Where migration flyways overlap, the virus can spread farther. “That makes our North American waterfowl just exquisite carriers and shedders of this particular pathogen,” says Bryan Richards, emerging disease coordinator at the National Wildlife Health Center within the U.S. Geological Survey.

Bird Flu Is Spilling Over into Other Animals

In Wisconsin, people noticed fox kits were strangely easy to approach, wandering alone, often stumbling or walking in circles.

The saga of this strain’s lineage begins in 1996, when domestic geese in the southeastern Chinese province of Guangdong began to die from uncontrollable bleeding and neurological symptoms. The flu strain responsible was given the unwieldy name A/goose/Guangdong/1/1996 H5N1 influenza A, a highly pathogenic avian influenza. The designation “highly pathogenic” is based on how contagious and deadly an avian influenza virus is in domestic chickens. Gs/GD refers to this flu virus’s specific genetic family. Despite the culling of birds on affected farms, sporadic outbreaks of Gs/GD HPAI continued throughout the region as the strain circulated among domestic poultry flocks, spreading through Southeast Asia. It has lingered in bird populations in the region ever since.

And it began to make wild birds sick. Gs/GD HPAI was found in gulls, herons, and flamingos. In 2005, at a lake called Qinghai, more than 6,000 bar-headed geese and other waterfowl fell ill with the virus and died. Ultimately it spread throughout Asia, Europe, Africa, and eventually North America in 2014 and 2015, devastating poultry and causing billions of dollars’ worth of economic losses. In that outbreak, only 100 wild birds in the U.S. were confirmed infected with Gs/GD HPAI, compared with more than 3,000 confirmed wild-bird cases in the current outbreak. Seeing waterfowl showing symptoms or dying from a flu virus they coevolved with was previously highly unusual. But that’s no longer the case.

“Now we seem to be seeing a lot of waterfowl mortality, which is just strange,” says Maurice Pitesky, a UC Davis poultry epidemiologist. “That’s not normal.”

Erupting in Europe and then North America

In 2020, Gs/GD HPAI exploded in Europe, striking domestic poultry and wild birds across the continent and lingering through the summers of 2021 and 2022, with no sign of relenting. Seabirds that nest in crowded colonies are especially vulnerable. In June 2022, at the De Petten nature reserve in the Netherlands, the virus devastated a breeding colony of sandwich terns over the course of a few weeks. An estimated 2,500 birds died, amounting to a loss of at least 39 percent of the colony’s breeding population, according to one source.

The Gs/GD HPAI outbreak has grown to affect 37 European countries, making it the largest wave of avian influenza ever seen on the continent. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reported 2,467 poultry outbreaks, with 48 million domestic birds culled and 3,573 confirmed cases in wild birds. The virus was also found in European mammals, including a porpoise in Sweden and a badger in Denmark that was spotted trotting in circles.

Migratory birds from Europe likely spread Gs/GD HPAI to birds in the Arctic that later spread it to the East Coast region of North America, according to a genetic analysis comparing the virus in infected birds on both sides of the Atlantic. While it would take further live bird testing and genetic tracking to fully confirm, researchers suspect that carrier waterfowl mingling in their summer breeding grounds in the Arctic spread the virus among themselves, then carried it along the Atlantic Flyway as they flew south the following fall.

“When they’re sharing time and space on the nesting grounds, it gives a perfect opportunity for these viruses to just spill into other waterfowl hosts,” says Richards.

The first confirmed case of Gs/GD HPAI in the U.S. was in a wild American wigeon in South Carolina, detected through hunter-harvested sampling in mid-January 2022. Wild American wigeons often nest in Canada and Alaska during the summer; they use every flyway on the North American continent and are one of the first species to migrate south to overwinter.

Next, the virus spread to the Midwest, wiping out a family of urban great horned owls in Minneapolis. The raptor center staff was heartbroken by the young owls’ vocalizations as they seized, unable to stand, and they eventually had to be euthanized. At publication, Gs/GD HPAI has killed 257 bald eagles across the U.S., as well as 116 red-tailed hawks. Vultures have been hit even harder: 404 black and 76 turkey vultures have perished.

Gs/GD HPAI arrives in California

Ashton Kluttz, executive director of the Bird Rescue Center in Santa Rosa, remembers hearing about California’s first confirmed case on July 14, 2022. “That was the very same day that we received a phone call about a mass mortality event of Canada geese, here in Sonoma County,” says Kluttz.

Soon after, the Bird Rescue Center became one of the organizations most affected by Gs/GD HPAI in the Bay Area, seeing about 50 suspected cases in the next month. The wildlife hospital observed suspicious symptoms in Canada geese, turkey vultures, pelicans, corvids, and various waterfowl. According to Kluttz, the Bird Rescue Center has received more than a hundred phone calls reporting neurological symptoms alone.

Across the Bay Area and the state, wildlife hospitals and bird specialty centers increased their biosecurity measures and braced themselves for a viral onslaught. At WildCare wildlife hospital in Marin County, susceptible species are now screened and triaged under an outdoor tent. California Fish and Wildlife recommends that wildlife hospitals not test birds showing suspicious symptoms, but instead euthanize them on the spot to minimize the risk of infecting other birds. It is thought that the virus can spread between birds from indirect contact with contaminated surfaces such as human hands, clothes, shoes, and even car tires.

WildCare workers have ratcheted up their biosecurity, changing shoes and clothes every time they come to the hospital and even donning full protective gowns, gloves, and masks when dealing with susceptible or potentially infected patients. “It’s a big burden,” says Juliana Sorem, a veterinarian at WildCare. “Everything is a lot more complicated, but I think that’s what we have to do right now.”

The abrupt and urgent turn to extensive personal protective equipment and quarantines was too much for at least one regular WildCare volunteer, who also worked as an intensive care unit nurse at a human hospital. He couldn’t bear the similarity to the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. “It took him back,” says Sorem. “The isolation gowns and the masks, and all the tarps and the shoe changes and shoe covers and all that—it was just too much for him.”

At Lindsay Wildlife in Alameda County, workers now wear protective Tyvek suits and disinfect all equipment with hydrogen peroxide. Testing every incoming bird showing suspicious symptoms would be too expensive for the hospital, which sees about 5,000 wildlife patients per year. Like at the other wildlife hospitals, patients with Gs/GD HPAI symptoms are euthanized. The carcasses are then double-bagged and frozen until they can be properly disposed of to prevent further spread of the virus. Lindsay Wildlife veterinarian Krystal Woo hopes that reliable rapid tests for Gs/GD HPAI will become available soon.

Meanwhile, the number of positive cases have continued to tick up in surrounding counties. By October, the virus was confirmed in sick and dead birds in Southern California and as far south as Mexico.

Looking ahead

Richards, who keeps a backyard flock of 13 hens, is grateful to live far from any ponds or wetlands where his poultry might intermingle with flu-carrying waterfowl. He worries that species known to carry avian influenza, such as mallards or blue-winged teals, will be maligned as they bring the disease across thousands of miles to new continents and victims. “Yes, the landscape is riddled with risk out there right now, but we don’t want to vilify the carriers,” says Richards. “They’re just doing their thing. They’re being ducks.”

With Gs/GD HPAI now circulating in wild populations worldwide, Pitesky, the UC Davis poultry epidemiologist, believes it will continue to spread until less deadly strains become dominant once again. But that might take a while.

“This model suggests that we’re going to have a lot of virus, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better,” says Pitesky. “Hopefully, eventually, waterfowl adapt to the virus, just like all viruses don’t want to kill their hosts.”

Since Gs/GD HPAI continues to decimate European wild and domestic bird populations, Richards suspects we might be in it for the long haul. As of December 2022, the U.S. has seen a total of 4,362 positive cases in 108 wild-bird species. And while cases can be counted and mapped, Richards feels like a spectator as the disaster unfolds. “We’re going to watch, we’re going to monitor, but are there things we can do that would help species recover, or be more likely to do better in the future?” he wonders.

For now, as fall migration begins in earnest, researchers and government agencies continue to track Gs/GD HPAI through its hosts. After a long day of swabbing, Mihalco, the APHIS biologist, labels her test tubes full of samples and packs them into boxes. She doesn’t know when she might hear the final results. Meanwhile, the Delta breeze sweeps through Grizzly Island’s grasses, ducks calling as they take to the skies.