Perhaps you’ve seen them strewn along the seashore: a smooth, round pebble with a perfect hole right through it, or a chunk of shale with several holes neatly arranged in suspiciously consistent rows.

“It strikes people’s curiosity,” says Rebecca Johnson, codirector of the Center for Biodiversity and Community Science at the California Academy of Sciences. “It’s really common along our beaches to see these hole-filled rocks and be really confused about what possibly could have made this hole.”

People from the British Isles have long called these uncanny rocks hagstones, holey stones, or witch stones. Some people believe the stones grant magical powers: sailors tie hagstones to the sides of their ships to ward off bad weather and witchcraft. Other traditions included hanging hagstones above beds to repel nightmares or in stables to protect horses, or wearing hagstone necklaces as protective talismans.

But what made these captivating stones in the first place?

“It’s absolutely the most common question I get as a clam guy,” says mollusk researcher Paul Valentich-Scott, formerly a curator at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. “It’s an enigma in nature, to have that kind of perfection.”

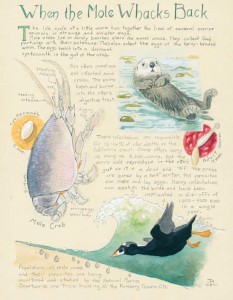

These perfect holes aren’t created by human hands or witchcraft, but are the life’s work of piddock clams, also known as angel wing clams. These enterprising mollusks excavate their custom shelters by slowly boring through soft rock such as sandstone or Monterey shale. “I call them living drill bits,” says Jonathan Geller, a marine invertebrate zoologist at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, part of San José State University.

Piddocks are members of the Pholadidae family of mollusks, which live in oceans around the world. After a clam dies, the hole it created remains in the rock. Waves tumble the rock, breaking it down into pebbles with cross sections of perfect holes, captivating beachgoers.

Piddocks begin their lives as larvae drifting at the mercy of the open ocean. At this stage, they measure only 300 to 500 microns wide—about the width of three human hairs. But even in their minuscule larval state, piddocks can “taste” the water and mosey toward signs of adult clam life, which entice them to settle near each other on appealing slabs of shale. (This is why rows of piddock holes may be crowded together.) If the rock surface feels and tastes right, the clams complete their metamorphosis from larva to juvenile. Then, the drilling begins. Gripping the stone with its suction-cup-like foot, the clam rotates its body, causing the ridges that stud the wider end of its shell to rasp against the rock like a file.

Fleshy tubes called siphons peek out of the clam’s shell toward the opening of the burrowed hole. The siphons suck oxygen- rich water into the clam’s body, where it sloshes over its gills and into the stomach. There, the tastiest morsels of plankton filter in and the siphons spit out the extra water.

Burrowing through even the softest rocks takes time. The clams toil away, deepening and expanding the hole by roughly a millimeter each month. Because the clams grow as they go, they can never leave their homes—not that they have any reason to. “For them, it’s not a price to pay,” says Geller. “They’re safe and secure.”

When a piddock dies, other creatures can take up residence in the burrow. Sea anemones, crabs, snails, and sea urchins find safe havens in these nooks.

Grinding on beneath the waves may sound tedious (or familiar), but the piddock is happy as a clam to carve its safe abode—in that sense, a hagstone as a talisman for protection may have some logic to it.

-300x225.jpg)