I never thought it would come to this: me killing a tree. Especially such a pretty one. Acacia dealbata–native to Australia, and probably planted here in the Sandhills of the Santa Cruz Mountains by past settlers or miners–no one knows for sure. Big, shady, and fast-growing, the acacia swarms with wide lacy leaves that fall to the ground and create a carpet of nutrient-rich duff–which is why it’s got to go.

Trees like this acacia don’t belong here in the Sandhills–exposed remnants of an ancient seabed now four miles from shore, located in and around the town of Scotts Valley in Santa Cruz County. Here in the Sandhills, an ecosystem has developed that is remarkably different from the surrounding habitats of mixed evergreen forest, with plants and animals that have evolved to survive in the porous, nutrient-lean sandy soil. Some of those creatures are found nowhere else in the world. And ponderosa pines grow here but are virtually never seen elsewhere in California at such low elevations. Once covering 6,000 to 7,000 acres, the Sandhills are now down to 4,000 (including only 2,500 that are completely undeveloped), displaced by home building, mining, and the introduction of nonnative animals and plants–like this acacia. Today the Sandhills, once contiguous, are cut into several fragments, owned and managed by different entities, including a state and a county park, and also separated by houses and a mining operation. Despite the fractured nature of the habitat, pieces of it still persist and, with a little help, just might survive a while longer.

I stand there holding a spray bottle full of herbicide, while beyond the doomed acacia’s ring of shade, searing sunlight reflects off the hot white sand of Sandhills chaparral. I’m in the Olympia Watershed: 180 acres owned by the San Lorenzo Valley Water District (SLVWD) northeast of Felton in the Zayante area (named after the sandy soil–the “Zayante series”–derived from the sandstone of the Santa Margarita formation). Opportunities are limited to visit this Sandhills portion of the watershed; a fence runs along the main road, blocking access. I’m here off-road only because my tree-killing companion, Ken Moore, has a grant from the SLVWD to help restore the area.

-

Ponderosa pines (background) grow at unusually low elevations in the Sandhills. In spring, this rare habitat is awash in flowers, such as these California goldfields. Photo by Jodi M. McGraw,

It’s October, and the Sandhills at this time of year aren’t as vibrant as they will be in the spring. The area is dotted with the dull sage green of the endemic Bonny Doon (or silverleaf) manzanita (Arctostaphylos silvicola), which won’t bear its small red fruits until later in the season. But in the springtime, the Sandhills bloom with the yellows, pinks, and purples of wildflowers, and visitors can join guided educational hikes along trails in nearby Quail Hollow Ranch County Park and, less frequently, here in the Olympia Watershed.

To Moore, who’s cleared about 35 acres of acacia over four years, each wildflower is a triumph–proof that despite steep odds, the Sandhills’ four endemic plants still survive: the Santa Cruz wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium), Ben Lomond spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana), Ben Lomond buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum var. decurrens), and Bonny Doon manzanita.

A former landscape architect, Moore’s done his share of planting nonnative ornamentals. “I’m spending the rest of my life atoning for my sins,” he says. Moore runs the Wildlands Restoration Team, a nonprofit that works to preserve natural habitat in the Santa Cruz Mountains, including the Sandhills.

Moore belongs to a diverse group of people who, enamored with this unique habitat and troubled by its destruction, have made studying and preserving the Sandhills a lifelong passion. The place seems to pull people in, even though it’s open to visitors only in spring and only on guided walks. But on those walks, you’re bound to hear about ornithologists and naturalists and botanists who’ve made the Sandhills their specialty. Ecologist Jodi McGraw says she did her dissertation on the Sandhills partly because she was intrigued by the area’s rarity and fragility, and also, as she puts it, “because the Sandhills are an ideal system to study how exotic plants alter the way natural disturbances, such as fire, affect endangered plants, such as the wallflower and spineflower.” A few years back, McGraw wrapped up the Sandhills Conservation Planning Project, an endeavor that mapped the Sandhills and identified key areas for conservation. These days, among many other things, she works to preserve the Sandhills through research, habitat management, and educational programs.

-

Santa Cruz monkeyflower (Mimulus rattanii ssp. decurtatus) rarely grows more than four inches tall and occurs only in sandy soils in Santa Cruz County. Photo by Jodi M. McGraw.

You begin to see things differently when you’re with Sandhills aficionados like McGraw and Moore, who have a reverence for the place and an uncanny ability to help you see it as they do.

So, back at the Olympia Watershed, when Moore suggests we take a break from killing acacias (which involves squirting herbicide into holes drilled in their trunks) and go on a walk, I jump at the chance.

The wind stirs up swirls of sand along the trail, and the white sand blazes under the pounding sun. If not for the redwood-covered hills in the distance, we could be in the desert.

Moore points out the two main Sandhills communities: northern maritime chaparral with Bonny Doon manzanita (known informally as Sandhills chaparral) and maritime Coast Range ponderosa pine forest (Sandhills parkland).

-

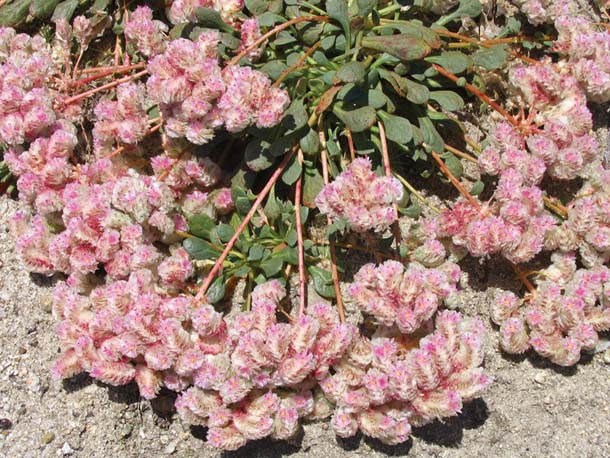

Pussypaws (Calyptridium monospermum) is normally found in the Sierra Nevada but also occurs in the Sandhills. Photo © Suzanne Schettler.

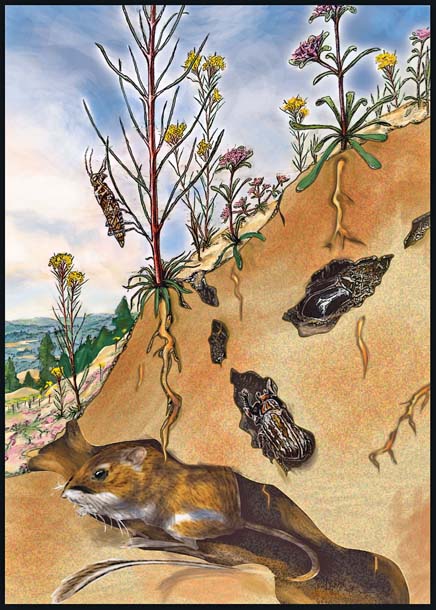

Sandhills chaparral is the dominant habitat, covering about 3,750 of the 4,000 acres; it tends to grow in flatter areas and on the slopes of ridges. Chaparral is home to the endemic, endangered Mount Hermon June beetle (Polyphylla barbata) and the Santa Cruz kangaroo rat (Dipodomys venustus venustus) and strewn with shrubs like the Bonny Doon manzanita and annuals like the Ben Lomond spineflower. Chaparral also hosts the Santa Cruz monkeyflower (Mimulus rattanii ssp. decurtatus), endemic to Santa Cruz County and occurring mainly in the Sandhills.

-

Ben Lomond wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium) is federally endangered. Photo © Suzanne Schettler.

Bonny Doon manzanitas dominate the Sandhills chaparral, with ponderosa pines also scattered across the area. Although elsewhere in California these trees are found at elevations of 3,000 feet or more, the Sandhills’ ponderosa pines grow at 600 feet, and some taxonomists think they are a separate species (Pinus benthamiana). Ponderosas survive in the Sandhills, one theory says, by absorbing water and nutrients through the fungi living on their roots.

Ponderosas also grow on the steep ridges of Sandhills parkland, which contains the widest diversity of endemic plants: Ben Lomond spineflower, Santa Cruz wallflower, and Ben Lomond buckwheat. Sandhills parkland is also home to the coast horned lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii), Mount Hermon June beetle, and Zayante band-winged grasshopper (Trimerotropis infantilis). Only five populations of these grasshoppers remain (in Quail Hollow and Scotts Valley), and the Sandhills parkland itself is extremely endangered–only about 250 acres remain.

Part of the reason is that the Sandhills are located in what has become a very desirable place for people to live. The towns of Scotts Valley, Felton, Ben Lomond, Boulder Creek, and Bonny Doon have been built in and around the Sandhills. Home building causes several problems, especially fragmentation, where remaining patches of habitat become too small to sustain plant and animal communities.

-

The distinctive chaparral of the Sandhills is home to the endemic, endangered Mount Hermon June beetle. Photo by Jodi M. McGraw.

Another challenge facing the Sandhills is the value of the sand itself. When the waters of the ancient sea receded, the sandstone of the Santa Margarita formation weathered down to a porous, high-grade sandy soil that drains rapidly. Its round particles and low impurities make it good for producing optics and glass. Six quarries operated in the Sandhills throughout the 20th century. One remains: Graniterock’s Quail Hollow Quarry, down the road from the Olympia Watershed. As part of its mining permit, Graniterock maintains a preserve at South Ridge–what McGraw calls “the crown jewel” of the Sandhills because of its biological richness. Of the 250 or so acres of Sandhills parkland habitat left, the 30 acres at South Ridge form the largest remaining parcel; educational hikes happen infrequently here.

Next to the quarry, Quail Hollow Ranch County Park offers more frequent guided hikes. Park interpreter Lee Summers has been leading these hikes, on Sundays in April, for about eight years. Why only in April? “Sometimes there aren’t any plants in bloom in March, and sometimes in May it gets too hot for hikes,” Summers says. Besides, she says, “wallflowers hit their prime in April, and it’s nice to show them off.”

-

In addition to endemic kangaroo rats and beetles that live most of their lives underground, the Sandhills are home to the Zayante band-winged grasshopper, which can use its wings to create a surprisingly loud crackling noise known as crepitation. Illustration by Brian Maebius.

Summers starts her hikes by talking about geology: how the sand settled in shallow ocean waters 10 to 12 million years ago, during the Miocene era, and became the foundation for the area’s rare habitat. She hands out laminated photos of plants found in the Sandhills and encourages hikers to watch for them as they wander for about two hours on the mile-long trail.

“The flowers in the Sandhills are so small, they’re called ‘belly plants’ because you have to lie down on the ground to get a good look at them,” says Summers. The Santa Cruz monkeyflower’s bloom, for instance, has a diameter of only a half-inch. But you can’t miss the pink carpets of the star-shaped Ben Lomond spineflower or the Santa Cruz wallflower, with its tiny bouquet of gold-yellow blossoms atop long spindly stems. (In April, you won’t see the creamy white pom-poms of the Ben Lomond buckwheat–these bloom June through August, after the Quail Hollow hikes have ended for the year.)

A closer look reveals how these plants have adapted to survive. Fine “hairs” on their leaves reflect sunlight and capture water, and small or waxy leaves reduce water loss. Further adaptations are underground, where long roots access moisture deep in the soil; dense, fibrous roots gather available soil moisture; and plants tap into other flowers’ root systems.

When hiking in the Sandhills, as locals like Moore will remind you, stay on the path and walk in the footsteps of the person in front of you. Moore’s passion for the place has led him to put up barriers to discourage motorcyclists. Still, as we walk through the Olympia Watershed, we see the scars of motorcycle tracks crisscrossing the sand. Moore admits it’s a problem, trying to figure out how the Sandhills can be protected when locals want to use them. Such recreational use is particularly hard on the burrowing kangaroo rat. Only one kangaroo rat population survives, and it is further threatened by fire suppression, which eliminates gaps in the chaparral canopy that support herbaceous plants, the animal’s chief food source.

-

Map by Ben Pease. Click for larger map.

Once he’s gotten rid of the acacia, says Moore, fire would be the best way to bring the ecosystem back in balance. Controlled burns already occur during the rainy season in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park’s Sandhills. But Moore calls such efforts “a PR challenge” closer to populated areas, like the Olympia Watershed. He admits that other methods, like raking away the duff, might make more sense.

“Raking away the duff.” It may sound simple, but when one considers the enormity of such an endeavor–or removing scores of acacias–preserving the Santa Cruz Sandhills seems almost impossible. Then again, there are people like Ken Moore, Jodi McGraw, and Lee Summers. And there’s also the chance that when others learn about this place, they, too, will be inspired to devote themselves to it.

Getting there

Access Olympia Watershed trails from the Zayante Fire Department parking lot (7700 East Zayante Road, off Mount Hermon Road, near Felton). The San Lorenzo Valley Water District maintains the area and had no 2012 guided hikes scheduled at press time. Find updates at slvwd.com. Quail Hollow Ranch County Park [Quail Hollow Road, Felton; (831)335-9348] offers guided hikes on Sundays in April. The lower part of the public Sunset Trail crosses a tiny bit of Sandhills vegetation. The Sandhills habitat in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park [101 North Big Trees Park Road, Felton; (831)438-2396] is best seen by taking the Pine Trail (accessible from the park’s campground area) to the observation deck.

The Sandhills Alliance for Natural Diversity (santacruzsandhills.com) and the Sandhills Conservation and Management Plan were sources for much of the natural history information in this article and can provide even more information about the Sandhills.

.jpg)

-300x200.jpg)