Midpen at 50

More pieces in this series exploring the open space district’s history and work.• Caring for the Land That Cares For Us How Midpen was born from a grassroots campaign.

• Room to Roam Connecting protected spaces is key to wildlife conservation.

• Dancing on the Peak Again The Amah Mutsun hold their first ceremony on Mount Umunhum in two centuries.

• Coexistence: Cattle Ranching Meets Sensitive Species When livestock and conservation needs align.

There’s nobody alive today who’s seen the headwaters of San Gregorio Creek the way it looked before it was logged. What is now El Corte de Madera Creek Open Space Preserve was an ancient redwood forest that helped catch and filter rain from winter storms. As water entered the creek and cascaded downstream, it nourished runs of steelhead trout and coho salmon that spawned in the creek’s lower reaches.

But in the mid-1800s, this intricate hydrological system began to unravel. First with oxen and shovels, then with bulldozers and excavators, loggers carved miles of roads through the mountains. At El Corte de Madera, they built so many roads that the map of the property looked like “a big bowl of spaghetti,” says former Midpen planner Meredith Manning.

But in the mid-1800s, this intricate hydrological system began to unravel. First with oxen and shovels, then with bulldozers and excavators, loggers carved miles of roads through the mountains. At El Corte de Madera, they built so many roads that the map of the property looked like “a big bowl of spaghetti,” says former Midpen planner Meredith Manning.

One such road was called Steam Donkey, named for the steam-powered winch that turn-of-the-century loggers used to haul trees out of the forest. Steam Donkey plummeted from the ridgetop west of Skyline Boulevard all the way down to Lawrence Creek.

“Back during the timber harvest days, it was all about getting timber out with the least amount of effort,” Manning explains. “So roads went as straight as possible from point A to point B.”

Hastily built and extremely steep, routes like Steam Donkey were more prone to erosion than an intact forest. Soil running off the scarred slopes wound up in San Gregorio Creek, clogging the spaces between cobbles where salmon once laid their eggs.

By the 1980s, parts of this forest had been logged three or even four times over. Midpen maintenance supervisor Grant Kern has spoken with longtime locals who remember the place before it became a Midpen preserve. “The way they describe it, sounds like they were basically doing recreational bulldozing out here,” Kern says. “We’d find tons of old beer cans and oil filters and whatever they left behind. This place got hammered.”

When it acquired the 2,800-acre property in 1988, Midpen inherited miles of eroding roads like Steam Donkey. In time, it developed a Watershed Protection Program to address the problem, coordinating with agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s marine fisheries service to reduce the amount of sediment washing into waterways. In keeping with its three-part mission to acquire, restore, and open land for recreation, Midpen has worked to undo ecological damage to El Corte de Madera—a place where the legacy of logging remains even in its name, Spanish for “cutting of wood.”

Since the early 2000s, Midpen crews have reshaped or replaced miles of logging roads within the preserve. They’ve upgraded clog-prone culverts, built footbridges, and added features that help water drain off the surface.

Where roads were too steep or washed out to stabilize, or where multiple routes closely paralleled one another, “we just unbuilt them,” Manning says. “We went back with dozers and excavators—the same machines that were used to build these roads in the first place—and we just physically made the roads disappear.” Altogether, Midpen treated five miles of trails, including the top half of Steam Donkey.

The “unbuilding” had its detractors: Steam Donkey’s steep, rutted upper section had become a proving ground for more daring mountain bikers. “A lot of these old skid roads were pretty gnarly,” Manning says. They were so steep, in fact, that even riders with the skill to ride down them often ended up pushing their bikes back up.

But even as Midpen workers were decommissioning logging roads like Steam Donkey, they were also creating something new: more singletrack. Purpose-built for people—not logging equipment—the trails are designed to follow the contours of the land, with gentler grades and less ecological impact.

From Oljon Trail, one such stretch of singletrack, it’s difficult to make out the logging road that preceded it just downslope. In the five years since Kern and his crew first came through with heavy machinery to fill in the road cut, a layer of leaf litter has accumulated over the scar. Electric-green ferns are already springing from the floor of the corridor, and in the coming decades, new trees will sprout from the duff. Eventually, all traces of the old Steam Donkey road will disappear.

Completed in 2019, the Oljon Trail was the final piece in Midpen’s Watershed Protection Program at El Corte de Madera. A 2020 stream-sampling study found evidence the work is paying off: a 62 percent drop in fine sediment during big storms, 24 percent less surface sediment, and 15 percent less sediment in pools—all good news for salmon populations downstream. And the trail additions, upgrades, and realignments have helped make the preserve one of the Bay Area’s most popular mountain biking destinations, with routes for every level of rider.

“Those results are heartwarming,” Manning says. “It shows the program worked. It was a win for fish, a win for people, and a win for forest habitat.”

“Midpen was born of community action, validated by the voter, and supported by the public from the very beginning,” Gessner says. “Our legacy will always be tied to community.”

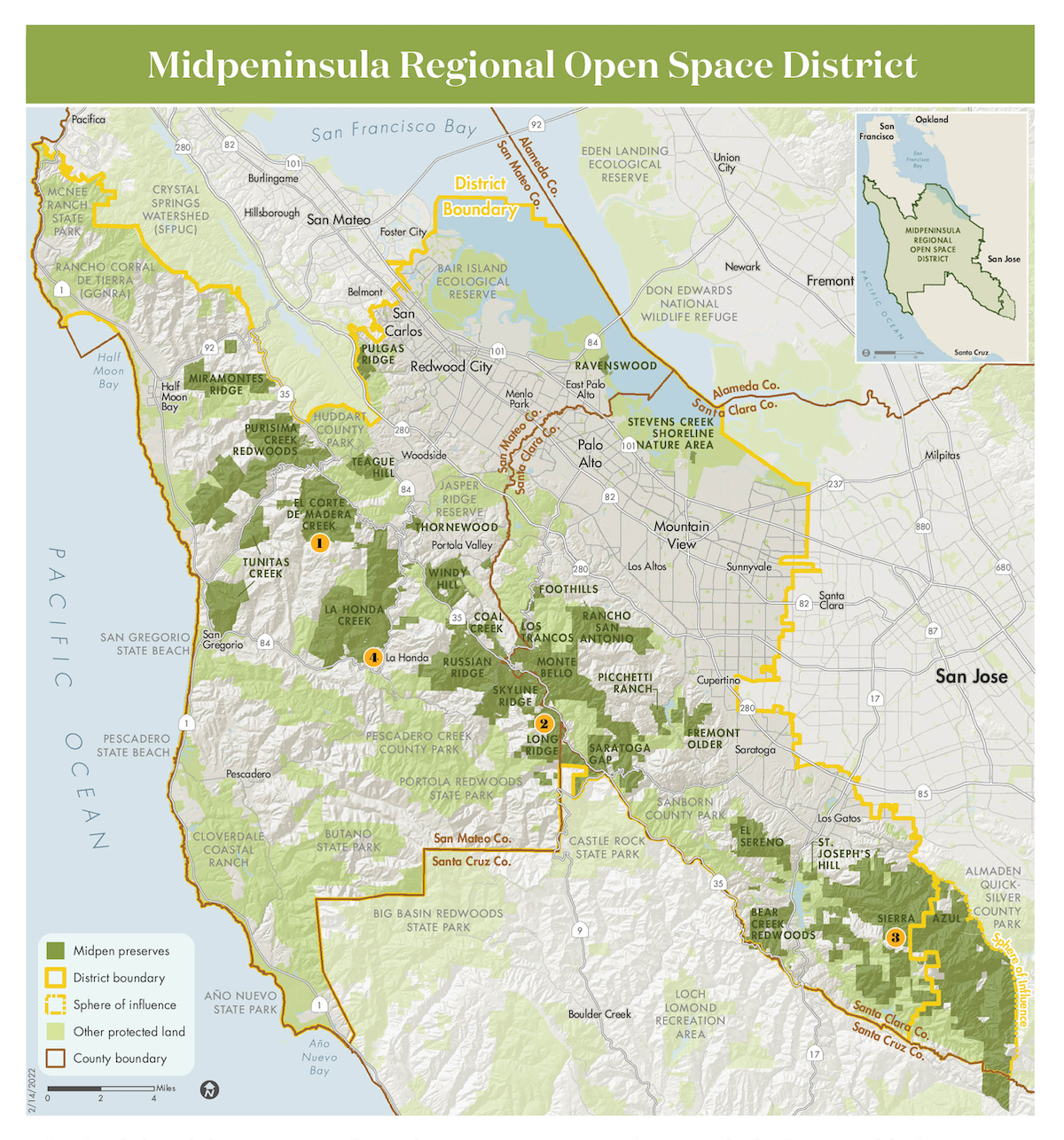

Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District is a public agency whose mission is to acquire and preserve a regional greenbelt of open space land in perpetuity, protect and restore the natural environment, and provide opportunities for ecologically sensitive public enjoyment and education.

On the San Mateo County coast, Midpen’s mission also includes acquiring and preserving in perpetuity open space land and agricultural land of regional significance, preserving rural character, and encouraging viable agricultural use of land resources. OpenSpace.org