“They started just as night set in upon their dangerous expedition. After a ride of two hours and a half they arrived at their destination. The fires were still burning, but the camp was abandoned. It was too dark to follow a trail…”

The dangerous expedition was led by California’s most infamous literary outlaw, Joaquín Murieta. The folk hero stars in John Rollin Ridge’s 1854 novel The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit—the first novel published in California, the first one published by a Native American, and a source text for future stories of masked avengers from Zorro to Batman.

The country that Murieta’s expedition traversed was California’s Diablo Range. Throughout The Life and Adventures, the bandit hero rides and hides amid the ridges and canyons of California’s Inner Coast Range. In 1854, readers would have known the land as the perfect setting for a romantic outlaw story. Even today, the 150-mile range of mountains from the Carquinez Strait to the oil fields of the southern San Joaquin Valley holds some of the largest remaining wild places in California. It is a rugged, remote, difficult realm, a biodiversity ark incised by the San Andreas Fault. It is a historic mixing place, where Central Valley Yokuts and coastal Ohlones traded and danced, where California’s ever-more-diverse future residents will seek escape and recreation.

And it is nearly unparalleled in ecological significance. A 2018 article in the scientific journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, lead-authored by UC Berkeley researcher Matthew Kling, mapped California’s species richness along with land protection status and showed the Diablo Range is rivaled in conservation importance only by parts of the North Coast Range and northern Sierra Nevada foothills. Bruce Baldwin, a co-author of the paper and curator of the Jepson Herbarium at UC Berkeley, added that it seems likely that plant evolution is happening faster in the Inner Coast Range, perhaps spurred by its dryness.

“It’s one of the most significant biological features in California that is relatively unknown by the millions of residents who live proximate to it,” says Andrea Mackenzie, general manager of the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority.

Despite their remoteness, these mountains are threatened—by suburban sprawl, by energy development, by proposed dams and reservoirs. But conservation leaders say a new era has dawned. This is just the beginning of the story. “The Diablo Range is the missing piece of the California conservation map,” says Save Mount Diablo Land Conservation Director Seth Adams. “Its time has come. In all kinds of different ways.”

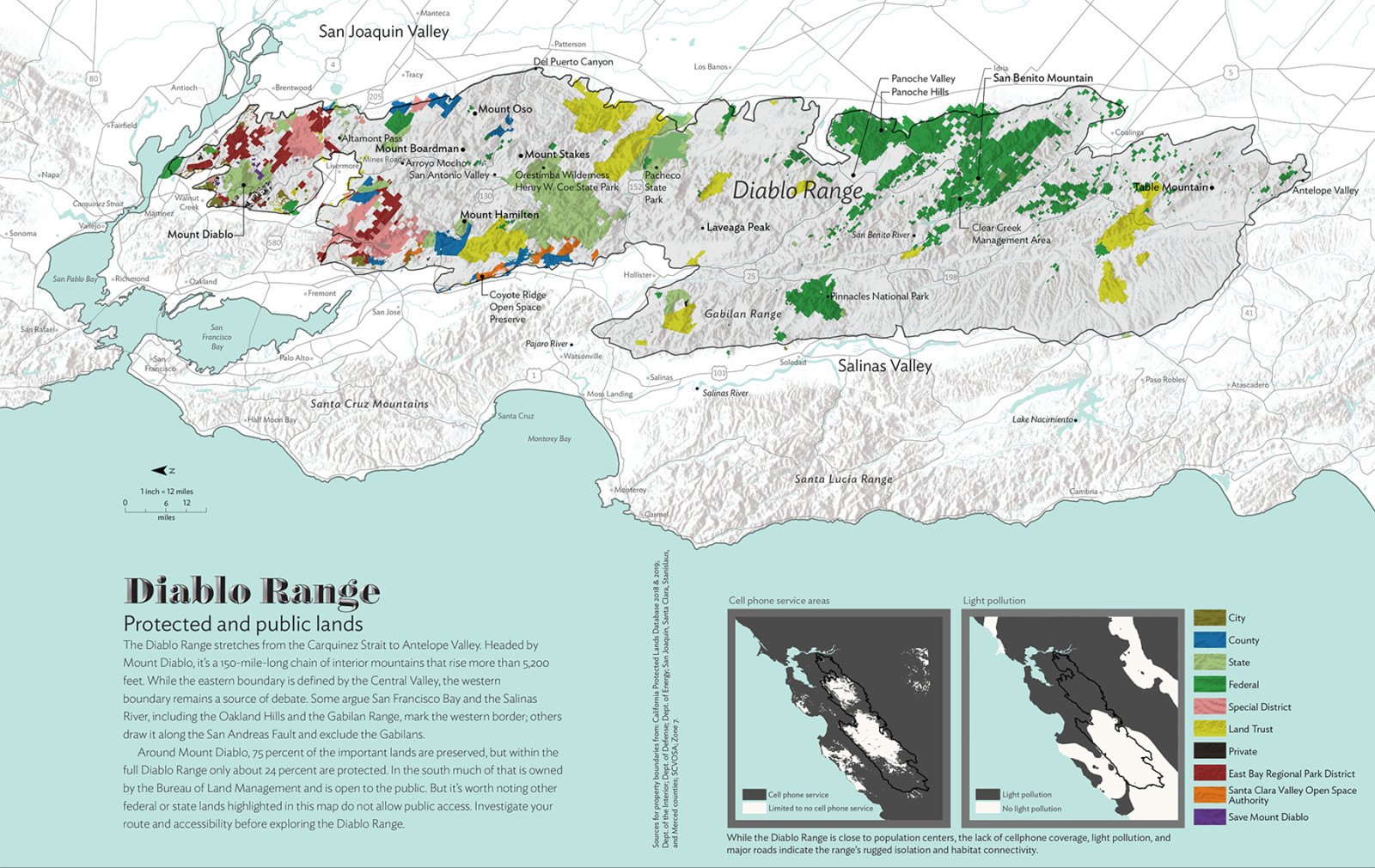

Maps abound of California’s mountain ranges. We have geology maps and topographic maps, land use maps and botanical maps, satellite image maps and highway maps. But to really get at the heart of what makes the Diablo Range unlike anywhere else in the nation’s most populous state, pull up a cell service map. There you will see a vast unconnected swath east and south of San Francisco Bay, extending all the way down to Kern County. The Diablo Range is a refuge from cellular civilization. You can drive in it for hours without finding a signal bar.

I’m not a stranger to back roads and wild places. I have driven hundreds of miles across corrugated Patagonian roads, honking sleeping guanacos out of the way. I have reversed down a hairpin Chilean mining road three feet from the grille of an angry dump truck. I have bounced with the pronghorn on the rutted back roads of Wyoming’s Wind River Range. It’s just that those places aren’t exactly what you expect to recall as you head south from the wineries of Livermore. Eight miles of blind turns on one-lane Mines Road, though: more Patagonia than Point Reyes. No cell service, no water, no emergency phone boxes, a long walk between lonely ranch driveways. The road even has its own Yelp page, where motorcyclists and bicyclists recommend it (26 reviews, 4.5 stars) as the ultimate in off-the-beaten-path Sunday rides.

Part of the Diablo Range’s power to fascinate derives from sheer size. As designated by the Department of Interior’s Board on Geographic Names in 1908, the range extends from the Carquinez Strait in the north to Kern County’s Antelope Valley in the south. It is the backdrop to Walnut Creek, the view west out the passenger window as you barrel south on I-5 and the view east out the driver’s window heading down U.S. 101. Neither view reveals what’s behind the first low foothills. Getting deeper into the Diablos is not simple: only two major passes bisect the range, the Altamont and Pacheco, and they are 60 miles apart. Huge portions of the range are held in private ranches, or in federal Bureau of Land Management areas accessible only by the sketchiest of dirt roads.

There’s no typical part of this mosaic, no county park of chamise and oak where you might say you’re in the heart of the range. It is too big, and too diverse, for easy description. Though ever-growing suburban California surrounds it on all sides, once you cross into the range its vastness overwhelms. What connects the Diablo Range together, and makes it one place, is precisely what you see on the cell coverage map: that you can’t connect to the rest of the human world from within it.

In the first written description of the Diablo Range, by the priest accompanying the Spanish Anza expedition in 1776, Father Pedro Font used the word “rugged” five times in two short diary entries to describe the party’s exploration south of Livermore. The 1850s newspaper accounts read by John Rollin Ridge called the Diablo Range the rocky aerie of criminals. Though historians think Ridge based his character Joaquín Murieta on a composite of several contemporary horse thieves and robbers, the place itself was as advertised. In 1853 a reporter for the San Joaquin Republican wrote, “This portion of the State is comparatively unknown; but in its solitudes and rocky fastnesses lie the retreats of hordes of desperate villains.”

In June 1862, an American surveyor named William Brewer rode into the Diablo Range at a place called Mount Oso, about 20 miles north of modern-day Henry Coe State Park. “Back of the treeless hills that lie along the San Joaquin plain, there rises a labyrinth of ridges, furrowed and separated by deep canyons,” he wrote in his journal. “This region is twenty-five to thirty miles wide and extends far to the southeast—I know not how far, but perhaps two hundred miles. It is almost a terra-incognita. No map represents it, no explorers touch it; a few hunters know something of it, and all unite in giving it a hard name.”

Galli Basson, a resource management specialist at the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority who’s worked on projects in the Diablo Range for the last few years, recalls the first time she went up into the western slopes of Mount Hamilton and looked east across the unbroken folds and ridges of the range. “In a way it gives you a sense of history,” she says. “You get this sense of California before massive development.”

Celeste Garamendi, who runs the Connolly Ranch outside Tracy with her husband, fifth-generation rancher Mark Connolly, says that when she first moved there after growing up on a ranch in the Sierra Nevada foothills, she found the Diablo Range dry and desolate. After 30 years, she’s learned to see the richness in the landscape. “When you’re along the range, you can visually see, and feel it with every part of your being, this critical linkage habitat corridor,” she says. “We can’t see directly into Livermore, but we can see the lights. You can see the Central Valley, just over the 30 years I’ve been there, the open spaces are filling in. What’s left is this Diablo Range.”

As in Patagonia or the Atacama Desert, there’s a sense of time immemorial inside the Diablo Range. The winding back roads, the ribbons of light in the creeks, the piles of fallen sycamore leaves, the cows grazing in pastoral meadows contribute to a sense of beguiling permanence. It’s hard to imagine this landscape as anything but what it is now, or as anything but the vision of past, unbroken, undeveloped California: the home of condors and the most densely populated region of freedom-loving golden eagles on the planet.

On maps of Native lands, the Diablo Range is an area of overlap between the Miwok, Ohlone, and Yokuts. Bay Miwok and Karkin Ohlone people lived around the Carquinez Strait and Mount Diablo. Between Mount Diablo and southern Livermore lived Chochenyo Ohlone, whose artwork on the walls at Vasco Caves, just southeast of the mountain, dates back 10,000 years.

Modern Santa Clara County was the home of the Thamien Ohlone. To the south in San Benito County lived Amah Mutsun Costanoan and Chalon Ohlone speakers, and Salinan-language-speaking tribes lived along the range up to its southern edge in Chumash territory. The eastern side, and most of the San Joaquin Valley, was inhabited by Northern (Delta) and Central Valley Yokuts. Though members of all of these tribes continue to live near their historic territory today, these tribes have, by Spanish, Mexican, and American policies and settlement, been almost erased from their lands.

After forcing the Ohlone of the Diablo Range into missions in San José, San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Juan Bautista, Santa Cruz, San Carlos, and Soledad, the Spanish and then Mexican governments carved the land into ranchos for settlers. Following the Mission period, some Ohlone returned to areas of the Diablo Range around Livermore, working on the ranches and establishing new communities. There was an Ohlone rancheria called Del Mocho, and some members of the once-federally recognized Verona Band of Alameda County lived there until the 1950s, which has now been forgotten, says San José State University anthropologist Alan Leventhal. “We don’t specifically know where that rancheria was located, because most documents that dealt with Indian affairs were kept so much on the margins,” he says. “Over the past decades, through cooperative archaeological investigations within the Muwekma’s ancestral homeland, we have [documented] in the greater San Francisco Bay Area 12,000 years of human history.”

The Diablo Range is a wonderland for California botanists. Part of its biological wealth comes from its geology, specifically massive deposits of serpentine rock that 30 to 140 million years ago formed on the seafloor and were then lifted up to form the fractured peaks and bandit-friendly fastnesses of the Diablo Range. Low in calcium and other nutrients and high in magnesium, serpentine deposits tend to harbor the rarest, most interesting plants in California—they are, naturally, one of the first things botanists look for.

The range is also a mixing zone, reflecting botanical influences from almost every part of the state. There are places where you can find trees like Jeffrey pine or incense cedar that otherwise live mainly in the Sierra Nevada. Two species of milk vetch in the genus Astragalus grow exclusively in the North Coast Range around Napa and Lake Counties—except for isolated populations 200 miles south on San Benito Mountain. There are places in the Panoche Hills where you can find wildflowers characteristic of the Mojave Desert. At least three flowers, Mojave cottonthorn, desert dicoria, and linear-leaved stillingia, seem to have been carried out of the Mojave by songbirds and dropped in the Diablo Range, where they now grow 200 miles from their nearest known populations. There are also many flowers found exclusively in the Diablo Range, like San Benito evening primrose, Mount Diablo fairy lantern, and talus fritillary.

“There are pieces from all over California tied up in this range,” says Heath Bartosh, senior botanist with Nomad Ecology, a Bay Area–based ecological consulting firm. “You could go somewhere, be blindfolded, take the blindfold off, and say, ‘Where am I?’”

Botanist Helen Sharsmith, exploring around Mount Hamilton in the 1930s, documented 761 different species of plants. As she pointed out in a 1945 journal article, that total amounted to 20 percent of the state’s known plant species and 57 percent of its known plant families living in less than 1 percent of its land area. Given all the private land that hasn’t been explored and remote BLM properties that have been visited only rarely, it’s likely there’s much more diversity to discover. “Who knows what undescribed species are out there,” Bartosh says.

Ryan O’Dell, who recently found both disjunct populations of Astragalus, says his job is mainly just to figure out what lives on the BLM’s 170,000 acres in the southern Diablo Range. “There are a lot of areas to find and a lot more to explore. Every year I find something I haven’t seen here before.”

It’s not just plant species that are relatively undocumented, he adds, but entire habitats. In some of the southern BLM lands you’ll find clay soils that swell with water and shrink and crack dramatically in summer. This “vertic clay” is less known than serpentine soil but home to dozens of rare California endemic species. In an email, O’Dell told me there are so few publications on vertic clay flora in California that he couldn’t recommend a reference, but he hopes to publish something himself in the next few years.

O’Dell grew up in Butte County and knew he wanted to be a botanist by the time he’d graduated high school. He studied serpentine plants at UC Davis and has spent the last 13 years studying plants in the Diablo Range for BLM. When he has time off, he spends it botanizing in other parts of the state. Harsh summers and muddy winters don’t faze him. I proposed to O’Dell that in many areas of the Diablo Range in July you might wander for hours in a shadeless, waterless 110-degree serpentine barren, breathing natural asbestos with every dusty footstep, and he replied, simply, “Yes, but that wouldn’t stop a botanist.”

The range is vital for animals, too. The Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority, City of San José, and Peninsula Open Space Trust partnered to pay $93.5 million to buy 937 acres in North Coyote Valley in November 2019, in part because the parcel is what they labeled a “critical linkage,” a link between the smaller and isolated Santa Cruz Mountains and the gigantic and interconnected Diablo Range. The Diablo Range, in the Open Space Authority’s estimation, is such a reservoir of biodiversity that if you simply connect up to it, animals can and will spill outside the area and into neighboring ones. In the same way the Rocky Mountains act as the spine of North America, harboring life from every part of the continent and allowing it all to meet, the Diablo Range acts as the spine of California.

“Our ability to preserve nature and biodiversity is a function of protecting core habitats through corridors,” says Open Space Authority Assistant General Manager Matt Freeman. “If you zoom out statewide, the Diablo Range would emerge as one of the most important core habitats in the entire state.”

The mountains shelter animal species great and small. The Diablo Range will be the source, Freeman says, for replenishing genetic diversity in the mountain lion populations of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Even as golden eagle populations decline in western North America, they’re holding steady here in California because of the Diablo Range. Tule elk, once numbering hundreds of thousands in the state, then hunted to near extinction by the 1870s, recovered quickly in the Diablo Range after reintroduction in the San Antonio Valley behind Mount Hamilton. For California condors, which have outgrown the Pinnacles, an unbroken mountain range presents the opportunity to someday expand all the way north to the Delta. Bay checkerspot butterflies, one of the first butterfly species added to the federal endangered species list, have their last stronghold along Coyote Ridge just above San José. The public can see them during spring at the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority’s 1,831-acre open space preserve once owned by United Technologies and used as a Cold War–era military rocket testing site.

“We’ve got these mountain ranges right here in our backyard and when we get up on the ridge and look east we can’t see a building for many miles, except the observatory on Mount Hamilton,” says Open Space Authority General Manager Andrea Mackenzie. “It’s mind-blowing! When members of the public, school groups, or city council members join us up there during wildflower season, they can’t believe this is the greater San José area.”

As a 5,400-square-mile north-south wildlife corridor connecting Kern County to the Carquinez Strait and an east-west corridor connecting the Central Valley to the outer Coast Range, the Diablo Range offers almost unparalleled habitat in a state that has fragmented almost everywhere else. As conservationists eye these mountains for future projects, that’s one of the first things they ask: where will the wildlife cross the road? “Think about it as a roadrunner,” Save Mount Diablo’s Adams says. “Think about it as a kit fox.”

For all its size and remoteness, the Diablo Range has never been immune to the depredations of the outside world. The geologic forces that made it haven for rare plants also made it a profitable site for mining and oil operations. In western Fresno County, Coalinga was for decades an oil boom town. The southern portion of the range is a hot spot for rare minerals, including the state gem, benitoite, and other parts of the mountains have been mined for copper, gold, mercury, and coal. Today, oil production is declining, and for the most part the mines have long closed. But tailings and poisoned ponds dot the range. There are two Superfund sites in the heart of the range, one near the mining ghost town Idria and another 10 miles south in the hills above Coalinga, both neglected. Clear Creek’s mercury levels grossly exceed federal limits. o

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

How to Explore the Diablo Range

»Mount Diablo

Visit the signature peak of the Diablo Range. The road to the summit museum departs from Danville and Walnut Creek, but numerous parks, including Mount Diablo State Park, flank the main peak, highlighting the mountain’s biological and geological diversity. Try a guided hike with Save Mount Diablo through its free public Discover Diablo hike program and explore around Curry Canyon Ranch, look for butterflies and fairy lanterns in Mitchell Canyon on the park’s north side, or explore the East Bay Regional Park District’s Morgan Territory for panoramic views from Bob Walker Ridge.

»The Mines Road Drive

Take in 30 miles of rugged Diablo Range scenery with a weekend drive out Mines Road. Stop for lunch at The Junction to chat up the bikers, then head west to the summit and telescopes of Mount Hamilton, or east out Del Puerto Canyon to I-5.

»San Benito Mountain Summit

You can drive all the way to the highest peak in the range, but it takes planning, caution, two permits from the BLM, and a high-clearance, 4-wheel drive vehicle. The road can be impassable after a rain or when the creeks are high, and it can be dry, dusty, and hot in the summer. Make sure you’ve got a BLM map of Clear Creek Management Area before you begin—Google Maps isn’t reliable for routes here and there’s no cell service in the area. The entrance to the management area departs from the Coalinga Road; find detailed route descriptions for this and other Diablo Range peaks on Peakbagger, a site for recreational summit visitors. Because it would be difficult to get help in case of car trouble, for our trip we took two vehicles.

»The Orestimba Wilderness Backcountry Weekend

Once per year, Henry Coe State Park opens the Bell Station road into the rugged Orestimba Wilderness, allowing campers, equestrians, and hikers access to one of the most remote parks in Northern California. The 2020 backcountry weekend will take place April 24–26. Reservations and more at coepark.net/bcw.

»Coyote Ridge Open Space Preserve

The Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority protected over 1,800 acres of serpentine outcroppings and spectacular wildflowers on the ridge overlooking east San Jose. Mark your calendar now: the Authority plans to open the preserve to the public in 2021 with several miles of new Bay Area Ridge Trail. Visit in the spring to see the endangered Bay checkerspot butterfly and unparalleled wildflower displays. More information at openspaceauthority.org.

The modern threats are more varied and widespread. In the northern edge of the range around Mount Diablo, suburban sprawl and development rise toward the foothills like the tide. Wind farms along the Altamont Pass are a slaughterhouse for raptors like golden eagles, and as the state looks increasingly to renewable energy, many more turbines will come online. Massive solar farms are creeping over the ranches of the Panoche Valley, dragging with them high-tension power lines that cut through previously open plains. At least some of the historic ranches face pressure to sell land. Fifth-generation rancher Darrell Sweet says California’s growing population brings commuter traffic around the ranch, resulting in more cars running into fences and more people wandering in his pastures. California High Speed Rail plans call for cutting across the Diablo Range near Pacheco Pass. The federal government sees many of the BLM lands in the range as ripe for fossil fuel exploitation. Every human project means a halo of roads and lights and litter, fragmenting one of the least fragmented landscapes in the state.

Save Mount Diablo’s Seth Adams has made it his mission to preserve this landscape. He spent his career working to protect the landmark peak that rises at the north end of the range, increasingly aware, he says, that Mount Diablo would lose its distinctiveness if it was cut off from the rest of the range to the south. He was already proposing the organization’s next expansion south when, in January 2019, he fell and snapped his quadriceps tendon. His first thought as he was falling, he says, was that he might never walk again. But soon his mind plotted a different outcome: he would rehab, and then he would push himself more and further than ever before. “I came to appreciate that this isn’t going to limit me; it’s going to spur me on,” he says. “Life is short.”

He had already fixed on the Diablo Range as the setting for his exploration. Adams has spent the previous 30 years working to protect Mount Diablo. He intends to spend the next two decades, he says, endeavoring to popularize and save the entire Diablo Range. He points out often that 75 percent of the ecologically important area around Mount Diablo has been preserved, while in the full 150-mile range, only 24 percent of the landscape has any protection. Save Mount Diablo’s first step: defining the range for a conservation community and public whose understanding hasn’t moved significantly since the days of John Rollin Ridge.

“The effort is to put this place on the map,” Adams says. “To get people involved, and [get them] to fall in love with it.”

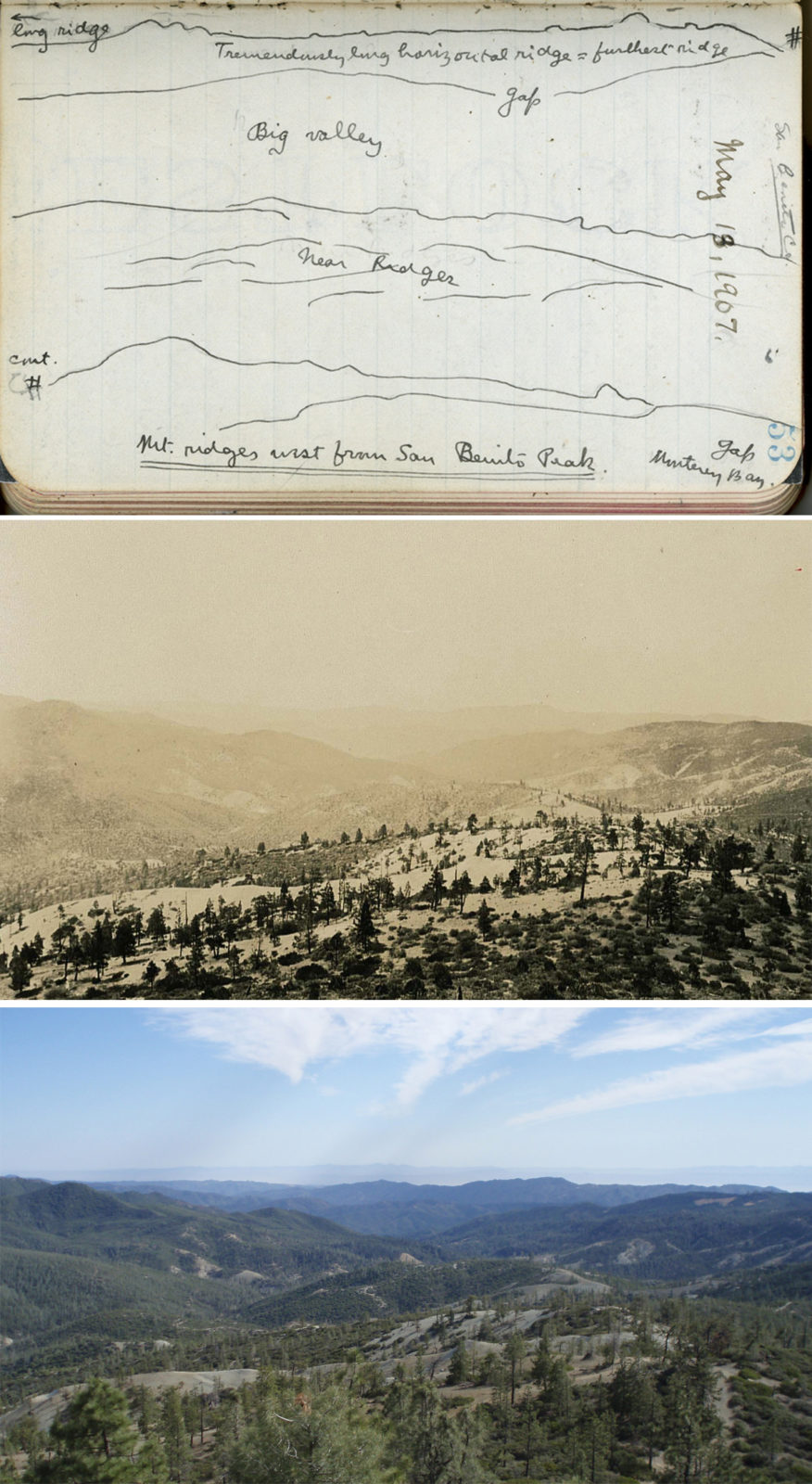

Late in 2019, I joined Adams and a group from Save Mount Diablo on a two-day road trip to explore the Diablo Range. Our goal was the summit of San Benito Mountain, at 5,241 feet the highest peak in the range. You can drive there, but not easily; it’s about 16 miles of tortuous, steep dirt roads from the BLM’s Clear Creek Management Area entrance gate, itself 15 miles of tortuous paved roads from the main highway. We took the long way from Walnut Creek, with Save Mount Diablo’s Executive Director Ted Clement driving the company SUV up and down and across all different parts of the range, while Adams talked from the back seat, sandwiched between photographers Al Johnson and Stephen Joseph.

Mount Diablo, Adams says, is the iconic peak for the whole endeavor. It’s special as the Bay Area’s signature urban mountain, surrounded by people and yet wildly diverse inside its park boundaries, a perfect metaphor for the entirety of the range named for it. Places throughout the range recall the better-explored, better-understood Diablo; as Clement put it at one point, climbing out of the SUV to look at a jagged line of rocks rising over Del Puerto Creek, “I feel like I’m visiting Mount Diablo’s family members, aunts and uncles.”

From the east side of Mount Diablo, you can see many of the pressures that face the range. Highway 4 runs through suburban sprawl and future planned developments in Antioch and Pittsburg. It turns past giant wind turbines, which scientists like USGS biologist David Wiens study for their eagle mortality rates. Wiens says it’s a constant push and pull between the eagles’ high death rates in the wind farms and the birds’ incredibly high birth rates—which of course depend on the Diablo Range remaining an ideal nesting and breeding ground.

The road winds south through green hills east of Brushy Peak, running up into the concrete wall of Interstate 580 at the Altamont Pass, an illustration of the challenges for wildlife in moving north-south through the Diablo Range. Adams, who spotted Contra Costa County’s first documented roadrunner out here 20 years ago, says you have to look closely at the freeway underpasses to see if wildlife like roadrunners or kit foxes can make use of them.

Outside Livermore the road narrows to one lane along the contour of a ridge above Arroyo Mocho. Beyond the winding arroyo lies the San Antonio Valley, where the elk now thrive, and Henry Coe State Park. The road splits at the head of the valley, with one route heading east out Del Puerto Canyon to Interstate 5 and one threading south up the east side of Mount Hamilton. Del Puerto Creek itself trickles through bucolic pastures, past outrageous ridges folded back and forth over each other, and bullet-pockmarked road signs. Red-tailed hawks circle overhead, and large raptors perch on almost every tree and pole. Much of the Diablo Range is dry, so the creeks become biodiversity hot spots within the range. “You can see why these green threads are so important in an arid landscape,” Adams said. “There’s water. There’s cover. There’s birds.”

Out on Interstate 5 the low hills block the view of the rugged range to the west. I’ve realized, as a lifelong Californian, how much my imagination had falsely compressed the space between 5 and 101, converting 40 miles of incredible ecological diversity into something more like a few miles I pictured as resembling the Altamont Pass. In the few areas where you can see farther into the range from the road, like where the peaks of the Orestimba Wilderness poke out beyond the California Aqueduct, it can seem like surely San José must lie beyond, and yet that’s just the first ridgeline. The Diablo Range is huge.

Fifty miles south in the Panoche Hills two streams have formed a 10-mile-wide plain between the ridgelines. “Imagine this is what the Livermore Valley looked like 100 years ago,” Adams says. “And anyplace there’s water, there’s somebody trying to use that water.”

Quail stream across the road by the dozen. Panoche is home to many of the plants more commonly found in the Mojave, and to some of the most interesting animals in the Diablo Range, including kit foxes and the blunt-nosed leopard lizard, a large multicolored lizard that can jump two feet in the air to catch insects. We piled out of the car at one point to admire the sunset, the last rays of light glittering in a tumbling small stream and glowing in the red rocks beyond. “We could be in Montana,” Clement said admiringly as he wandered along the roadside.

Yet the threats have arrived here, too. The massive Panoche Valley, which Brewer complained was “naked, dry and desolate,” is now the site of a 1,300-acre solar farm. And if Panoche represents the future of California energy generation, the similarly sized Coalinga Valley just to the south holds its past: 1,600 active oil wells, still pumping and steaming, which over the last century have drilled more than 912 million barrels of oil from the now-nearly exhausted ground.

We drove along the Coalinga Road west past the wells, on the way to the southern entrance to the BLM’s Clear Creek Management Area and the road to San Benito Mountain. “Five miles in and 500 feet up,” Adams says, and everything changes. Wells give way to pastures again, the hills close behind and cut off the view to the rear, oaks and chaparral appear, and it’s “Mount Diablo multiplied.”

The headwaters of the 109-mile San Benito River trickle along the roadside past sycamores and oaks. The route to the mountain summit turns off the Coalinga Road and into the BLM land with an immediate ford of the river where it meets the 8.5-mile tributary Clear Creek. A rutted dirt road tracks back and forth through the creek bed, crossing it around a dozen times before turning sharply up via a series of hairpin turns to the ridgeline. The serpentine barrens rise incredibly from the creek, vast, red-tinted hillsides, shining like wet clay, punctuated by rockslides and the occasional lone manzanita or yucca plant.

We drove for four hours, up and around, along precarious ridges and down old mining slopes, and finally into a small forest of pine and cedar near the mountain summit. Then even the trees gave way to a vast thicket of big berry manzanita and serpentine endemic scrub oak, and the road stopped at a radio tower and a small outcropping of rock marking the very highest spot in the Diablo Range. Stepping out into a cold December wind, we took in the incredible summit panorama: west to the sharp purple peaks of the Santa Lucia Mountains; north over the rain gradient from pine to oak to the arid Panoche Hills; east across the San Joaquin Valley above the tule fog to the snowy wall of the Sierra Nevada; south to where the Diablo Range descends for the last time into the Carrizo Plain and the Temblor Range. “It’s like Mount Diablo before pavement,” someone said, wonderingly.

The two poles of the Diablo Range have their differences. Mount Diablo rises so steeply out of the surrounding suburbs that to stand at the summit and gaze out is to get an impression of limitless horizons and the vast sea of encroaching humanity—it’s visible from half the state. San Benito Mountain feels more like a summit in the High Sierra: a place where you know you’re in a mountain range. The view encompasses peak after peak, unbroken ridges folding on each other into the distance as far as you can see. “Chain after chain of mountains, most barren and desolate,” wrote William Brewer after climbing here in 1861. “It was a scene of unmixed desolation, more terrible for a stranger to be lost in than even the snows and glaciers of the Alps.”

In a crag in the rocks we found a small mason jar with a spiral notebook inside. The previous entry was ten months old, by a parks biologist named Paul Johnson, who wrote, “Found this by accident. Up here studying moths.”

Adams took the guest book, thought for a few minutes, and added his own contribution: “From Mount Diablo to San Benito Mountain.” He then asked Clement to step down from the rocks so he could take his place as the highest person in the Diablo Range.

It is always easy, from the top of the mountain, to look ahead. But there was a sense that this was a summit we’d see again. The Diablo Range, with its north-south length, elevation changes and incredibly varied topography, is the very definition of a critical wildlife corridor in the time of climate change. Its combination of unprotected open space and clear recreation potential make it a one-of-a-kind target for California conservationists in the next few decades. Joaquín Murieta’s range is the future of California, and here, from its highest point, looking north across unbroken hills and canyons until the land, still undeveloped, disappeared from view, we could see what the future looked like.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the acreage of the solar farm in Panoche Valley.