I loaded my backpack with everything I thought I’d need for a three-night trip: hammock, sleeping bag, 100-foot rope, rock-climbing harness, carabiners and webbing, rain gear, headlamp, six peanut butter sandwiches, a $20 bill, a knife in case I got tangled in my rigging and had to cut myself free. It was already afternoon when I left my apartment on Dolores Street and headed west, uphill, in the direction of Twin Peaks. Mockingbirds talked across the bright sky. Babies babbled from their strollers. And the trees, as anticipated, were bountiful, beautiful, and diverse. Mike Sullivan, an obsessed amateur botanist and author of the urban field guide The Trees of San Francisco, has identified 274 species growing in the city. There are Washington thorns and cockspur coral trees; jacarandas, cajeputs, and Chinese photinias; sweetshades and golden rain trees; spotted and lemon-scented gums; pin, cork, and holly oaks. I didn’t know the names of most of what I saw, but it wasn’t names, after all, that I intended to climb.

My plan was really more of a prompt, a nudge from me to myself in the direction of urban-arboreal adventure. I’d wander San Francisco, neighborhood to neighborhood, park to park, paying attention to trees. I’d pay attention to ants and squirrels and clouds and my own shifting thoughts as well, but mostly I’d focus on the trees. When I found one I liked, probably a big one, I’d climb it, string the hammock as high as I could, and lose myself in the dreamy sway and drifty weave of green smells, green sounds, green moods. This would be a new city, a lofted metropolis of branch and twig. I’d rock to sleep, wake with dawn’s birds, rappel to earth, go get a cup of coffee. Maybe I’d be downtown, at Union Square or the Embarcadero. Maybe I’d be in the Presidio or out by the zoo.

Strolling along, I began noticing more and more of the particularities of the trees I passed. By creating a situation in which I needed a tree to sleep in, a situation where without a tree I was just your average drifter, I’d tricked my mind into a new type of attunement. Magnolias I’d walked by a hundred times demanded consideration. A ginkgo with yellowing leaves stopped me in my tracks. Crown structure, exact location in relation to buildings and power lines, degree of rot in dead and dying limbs — all of this was now of the utmost importance. I stared, scrutinized, kept moving. The perfect one was out there, somewhere.

I made a mental map of trees I could come back to should nothing better turn up. A California pepper tree in the Castro had a sweet umbrella shape to it but leaned against someone’s second-story window. A ring of eucalyptus on Tank Hill promised amazing views of the Financial District but the trees themselves were unappealing, their hammock sites few and tricky to access. I liked one Monterey cypress a great deal and was pretty sure I could finagle my way up into the crown, but when I followed the trunk downward it disappeared behind a fence, into a backyard. This got me thinking. The cypress’ roots extended out beneath the street – I could imagine them pulsing with water and nutrients below the blacktop – and visually the bulk of the tree inhabited an airy public space. So whose tree was it? I was a bit miffed: To hog a tree like that! To lock it away and deny it a hammocker’s companionship! But at the same time, I was also conscious of the dubious legality of my whole enterprise. Best to leave it alone; go find something with some privacy.

Norfolk island pine (too boingy). Cliff date palm (too frondy). I felt like a sailor navigating by stars, except my stars were explosions of chlorophyll twinkling in light wind above a sea of roofs. Tree by tree I worked my way to the top of the Mount Sutro Open Space Reserve, a mostly undeveloped 61-acre area at the city’s geographic center. The afternoon was easing toward dusk, my anxiety about finding a place to sleep beginning to rise. I followed a shuttle bus into an apartment complex where the trees, mostly eucalyptus, were out of my league, ascension-wise. I’d learned technical tree climbing techniques while working for the U.S. Forest Service on a study of northern goshawks (we had to nab the nestlings to band them), but that’s not to say I’m confident around either heights or knots; climbing is risky work and generally not to be messed with after dark. I needed to find my perfect tree. And soon.

The coast redwood is a Northern California icon; it’s the sparkle in John Muir’s eye, the poet Jane Hirshfield’s “great calm being” that “taps at your life.” As a human body provides a vast terrain for mites and other roaming micro-critters, a redwood’s body provides habitat for warblers and salamanders and epiphytes. Redwoods can grow to well over 300 feet tall and live more than a thousand years. They’re skyscrapers, fogscrapers, living towers with corridors and chambers and rooms and balconies and elevator shafts and fire escapes and rooftop patios. Though they’re not native to the San Francisco Peninsula, they grow just south, north, and east of the city. Some have been planted here, and they do just fine. So it probably comes as no surprise that in searching out a hammock-hotel there atop Mount Sutro, I found myself checking in at the trunk of a Sequoia sempervirens.

Mine was around 100 feet tall, by no means a monster, but then again, an absolute monster. It made a nearby lamppost look like a wee sapling and rose considerably higher than the four-story apartment buildings across the street. It spoke to me, this friendly monster, calling me up into its complex heights. Its language was presence, massive, and inviting, not heard but felt. I know it’s unscientific and weird, but this is the truth: Hey there little guy, the tree said, why don’t you grab that low branch of mine and see where it leads?

The redwood isn’t just a major Bay Area player; it’s also the quintessential adventure tree, a botanical Everest. In college, around the time I started hanging hammocks higher than three feet off the ground (I was into rock climbing and forest ecology), I read an article in The New Yorker about the search for the world’s tallest trees. The article, written by Richard Preston, profiled Humboldt State biologist Steve Sillett, a guy who spends days on end in the redwood canopy living out of a harness and a hammock. Preston’s book on the subject, The Wild Trees, argued that the upper stories of a redwood forest are as little-known as the depths of the ocean. Hyperion, the tallest tree on earth at 379 feet and change, lives in an undisclosed location in the tangled backcountry of Redwood National and State Parks. Epic storms, Tyrolean traverses, automobile-size chunks of debris crumbling loose above helmeted scientific heads: I burned through my copy of The Wild Trees in a weekend.

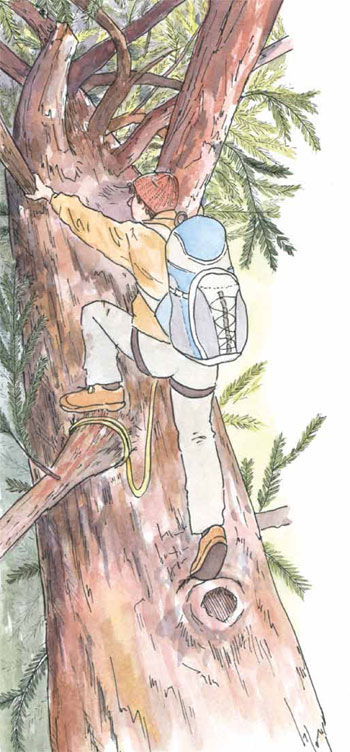

Organizing my gear and nerves in the duff beside the sidewalk, I kept reminding myself that I’m no Steve Sillett, no expert, and that I needed to be methodical and slow. Overhead, a thousand or more branches radiated out from the redwood’s perfectly straight bole in a maze of ladders, the lowest ones almost within reach. With all those holds I wouldn’t need the long rope, just the harness system and my own monkey style. By anchoring loops of webbing to limbs as I climbed, I could move upward without ever risking a major fall. I might slip off a branch, drop five feet, knock my noggin, and dangle unconscious for a spell, but at least plummeting to my death was out of the question. Once I left the ground, I would never take the harness off, not to sleep, not to pee, not for anything. In a sense, the tree would save me from its own dangers.

I double-knotted my shoelaces, tucked my shirt in, then jumped for the first branch; I missed it, jumped again, pulled, contorted, and got it underfoot. A young lady in a purple jacket walked by, and I held my breath. Though I was plainly visible, only ten feet away and no more than eight feet up, she didn’t see me. A man with a briefcase passed, then a grandma with a toddler and shopping bags, then another shuttle bus. Nobody looked up. So quickly I’d crossed over to the secret city above.

You scrape your legs and hands, get needles in your hair, hook branches with your elbows, your armpits, your ankles and the backs of your knees. You impress yourself on the tree and the tree impresses itself on you. It’s like Robert Frost’s poem about apple picking, the one where an “instep arch not only keeps the ache/It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.” Your body learns the tree though this touching, this ache and pressure. There’s some mysterious reciprocity here, some deep rapport between beings.

It might be worth recalling that image I mentioned earlier, a mite orienteering the landscape of a human body. As I climbed higher I became smaller and smaller, the tree larger and larger, until I was absorbed in full. The other world, call it “Below” or “the Ground” or “the City I Once Knew,” dropped away like so many kicked twigs and fluttering chips of bark. Sure, sounds filtered through the walls of foliage – sirens, kids yelling – but they were removed, distant and less than real; they came to me the way an alarm clock filters through a dream. What was real was the near at hand, the wood in my hand, this hold and the next and the next, again and again.

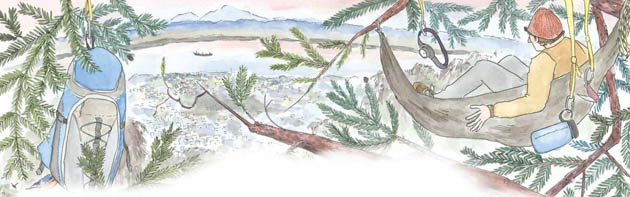

After 80 or so feet — maybe somewhere near the tree’s collarbone? — I stopped, my attention drawn from the climbing for the first time in a half-hour or longer. Something pink caught my eye through a window in the boughs: the Bay reflecting the sunset sky, a huge view of toy-size cargo ships and the Oakland Hills. I looked around. Another window opened to the north: the Golden Gate Bridge, Mount Tamalpais spilling ridges to the Pacific, blue folds of land fading into the distance. I’d been in the meditative trance of Do Not Fall, of effort and exhaustion, and was only now awakening. A red-breasted nuthatch emerged, landed nearby, gleaned an insect, and dissolved back into green. Again the tree spoke: This is your spot, little man. Make yourself at home.

It took another half-hour of tiptoeing around to rig the hammock, stressing the whole time about bobbling a key piece of gear and watching it plummet, but when the chore was done I really did feel at home. My supplies hung on lines I’d strung up, everything within arms’ reach, like a kitchen in Tuscany with herbs and salamis and pots and pans dangling from the ceiling. I was at ease, leaping over gaps, swinging in my harness, even balancing on one foot with no hands just for fun. I took off my sneakers and socks and let my sweaty feet dry against the tree’s cool, rough skin. I tested different seats and figured out a way to recline across three branches. A part of me wondered if the hammock was necessary.

Two scrub-jays stopped by for a chat. A red-shouldered hawk shrieked. I ate a peanut butter sandwich and watched the city’s lights rise from the gloaming in yellows, reds, oranges, and electric blues. It got darker. A neon glow leaked through the gaps and cracks in the foliage walls. I ate another sandwich and flipped on my headlamp. The top was out of sight but only 20 feet away.

The trip would go on for another three days, with overnight rest stops in a wind-tortured, rain-lashed cypress by the ocean, and a redwood in Golden Gate Park that only let me get 50 feet up before scaring me back down to a cramped hammock site. I hobnobbed with the homeless, walked dozens of miles, bought a slice of pizza, studied trees from afar, from below, from inside and out. Each was different, a unique portal providing access to itself and to some new perspective on the city. The trip was everything I’d hoped for: a series of engagements, a sequence of invitations. But nothing beat that first night’s redwood. Those long relaxed minutes up there at the “summit” were the literal and figurative high point of the adventure.

The trunk tapered down to the diameter of my wrist and I took a seat on a branch the diameter of my thumb, then reached up and touched the utmost tiptop of the tree for good measure. I tied in twice, just to be safe, and to my surprise I actually did feel safe. In fact, I felt as safe as I’ve ever felt anywhere in the city: no threat of creeps or thieves, no fear of getting hit by a car in a crosswalk. The night embraced me like a fat firm hug. A dog barked. A car parked and turned off its engine. I watched a middle-aged couple preparing dinner in one of the nearby apartments but lost interest pretty quickly; the city lights were better. Hirshfield’s line about a “great calm being” came back to me, and for a long while I felt that way, like a redwood, both great and calm. It was mellowness by association, I guess. There was no wind. All was soft and still. Nobody on earth — no human, at least — knew where I was.

Again, it’s weird and unscientific, but as I paused there in that soupy dark stillness 100 feet off the ground the thought did come to me: I never asked this tree for permission. In my excitement, first over the climb, then over the hammock site, I’d plumb forgot my manners. It’s not like I really deeply believed it was something I had to do, like the tree would be angry if I didn’t, but it was a courtesy, and I am, or at least I try to be, a courteous man.

So I started to say something, some thanks and praise, some little poem of gratitude for offering me this unique experience. As soon as I heard the words aloud, though, I shut up. Or maybe the tree shut me up. All I know is that I felt silly, not because I was talking to a tree, but because I only now realized that I’d been talking to it all along; I’d heard the redwood’s voice, why wouldn’t it have heard mine? It dawned on me that anything that needed saying had already been said, and moreover, said with a clarity no human words could ever achieve. It was the clarity of climbing, of touching. It was the language of bodies, of presence. My host knew everything I was thinking. I knew it knew this — don’t ask me how.

The dog barked again and I began my descent, back to my cozy hanging bed. Then, in a flash, it was broad daylight and I was on the ground, roaming, coffee in hand, a thousand trees greeting me with arms — I mean, limbs — spread wide in welcome.