More than 66 million trees have died in California in the past six years of withering drought. With dry periods expected to be more common in the future, scientists want to know which trees are most vulnerable.

A team of researchers led by William Anderegg at the University of Utah analyzed 33 tree-mortality studies from around the world to come up with answers. Just as you can identify high-risk disease factors in humans, Anderegg’s group found, you can identify traits that increase a tree’s risk of suffering a lethal embolism—a phenomenon “akin to a tree heart attack,” Anderegg said in a press release from the National Science Foundation, which partially funded the research.

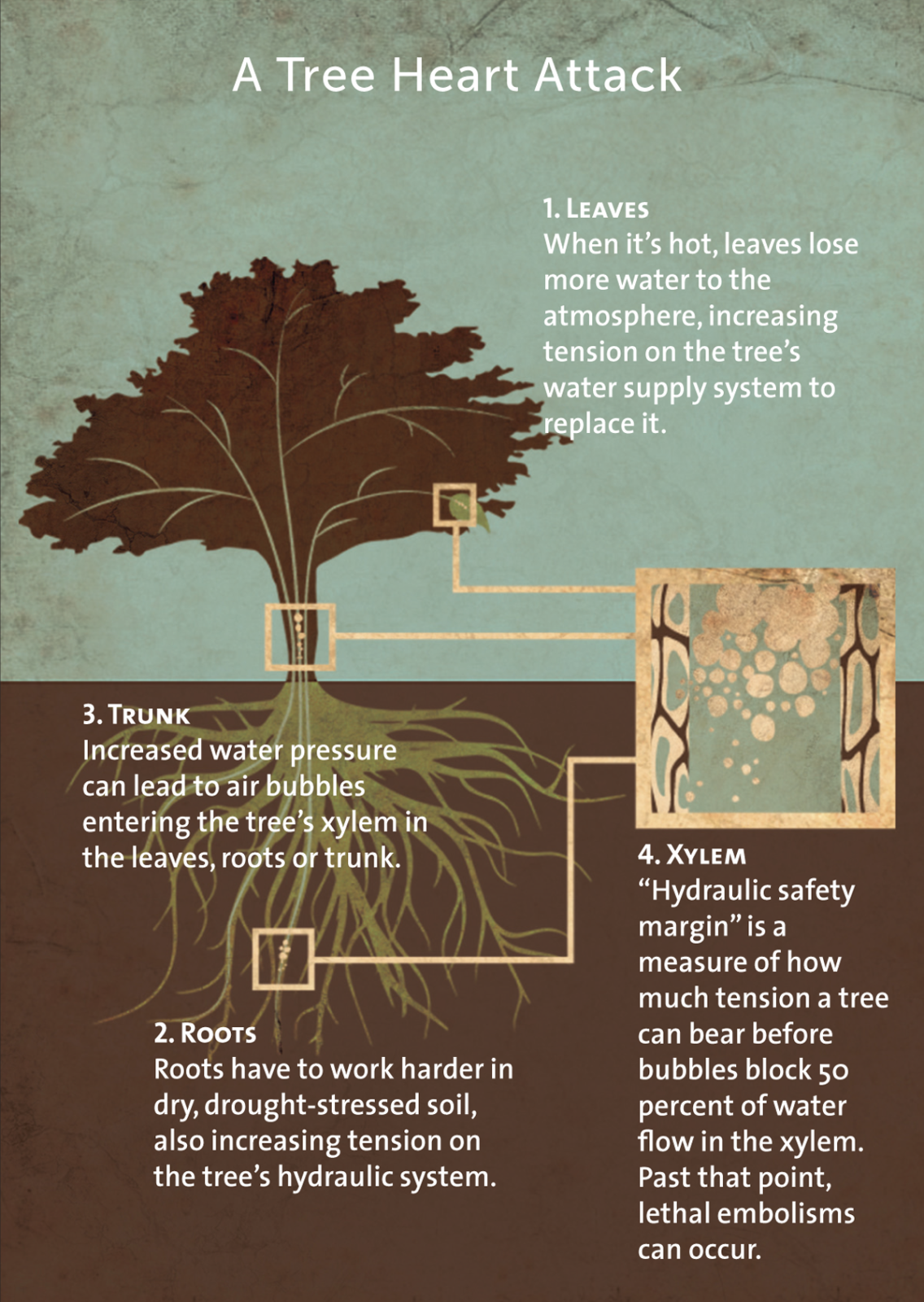

The predictive traits all had to do with the way trees move water internally. When conditions in the air and ground are dry, tension builds within a tree’s vein-like xylem system. When the tension gets too great, air bubbles can enter the xylem, partially or completely blocking the flow of water in the same way a human embolism blocks the flow of blood through a vein.

What makes trees most prone to fatal heart attacks? Some of it has to do with lineage. In Anderegg’s analysis, gymnosperms, such as redwoods and pine trees, were as likely to die from drought as angiosperms, such as oaks and aspens, but for different reasons.

Gymnosperms have strong xylem that can withstand high tension, but less ability to cope once the tension does rise to a damaging level. Angiosperms have lower tension thresholds but better tolerate stress in general. So to predict which trees will suffer in drought from embolisms, says Stanford environmental scientist Chris Field—a past collaborator of Anderegg’s—you’d have to look at both a tree’s characteristics and its environmental context. Not so different from human health.